Review / MISSION OSLO

This year the 8th edition of Oslo Architecture Triennale took place in Norway. With the theme "Mission Neighborhood", this show highlighted the relationship of architecture to the everyday, the living space nearby.

The Oslo Architecture Triennale is specific in that it addresses societal themes more than other similar architectural shows in Europe. For example, the theme of migration (the second version of the Rojava Parliament by artist Jonas Staal was exhibited here), sustainability and, in the last edition, the theme of minerals in architecture. That is why we decided to visit the Triennale after several years of watching it from afar and, together with the whole collective of the Society, of which we are members, we travelled to Norway as part of our strategic planning.

This year was no exception – the theme at the border of social sciences, politics and architecture raised our expectations. The theme of neighbourhoods, according to curator Christian Pagh, proved to be especially relevant in a post-metal world where “our living space has been reduced to the neighbourhood”. It speaks of the everyday, but also builds on trends in global urban discourse such as the 15-minute city or pedestrianisation. Decades of well-known concepts were thus given space at the prestigious architecture show. In the context of this thinking, it seems at first glance that this topic will no longer bring anything new. Especially in our context, words such as ‘neighbourhood’ or ‘community’ have become increasingly used in recent years and are more the language of marketing or politics than the language of architecture.

Mission to deconstruct the neighbourhood

The post-war era brought a new housing policy in Norway: the expansion of the social housing stock. It was, among other things, inspired by Perry’s 1929 model of the neighbourhood, which was to be composed in such a way that it could meet the needs of its male and female inhabitants – especially families with children – within an accessible radius of 400 metres. Pro-family policies meant that, until 1957, people living on their own did not have access to amenities such as social housing. This also caused discrimination against the LGBTQ community in applying for housing, who were denied these rights until the 1980s.

And so it seems that in the Norwegian vocabulary, neighbourliness is not only a trend of recent years, as it is here, but above all a policy that requires some deconstruction – a reframing. For Christian Pagh, curator of the Triennale, neighbourhoods are “the sum of the everyday places we share with others (…) but also the context where the structures of the whole society are revealed.” Exploring these structures, however, requires stepping beyond architectural practice – back into politics – to be engaged.

The Toyen Museum, which was left empty when the new Munch Museum was built near the famous Oslo Opera House, was the central venue. For the duration of the Triennale, this space was transformed back into a lively place, although still rather inhospitable in its acoustics. The elaborate floor plan hosted three exhibitions, several installations and also a large part of the accompanying programme. The main exhibition, “Mission Neighbourhood: (Re)forming Communities,” reflected precisely on the need for more diverse, sustainable neighbourhoods through a patchwork of 25 examples under the umbrella of six supporting themes: Understanding Places, Social Infrastructure, Our Streets, Natural Neighbourhoods, Reforming Systems, Artistic Approaches. The examples, mostly from northern and western Europe, represented urban projects at the scale of the house, street and neighbourhood – from neighbourhood mapping and atmospheric recordings to complex revitalisation projects or the construction of new neighbourhoods in Vienna or Copenhagen. Like most similar formats, this exhibition struggled with a common problem of architectural or art shows – how to piece together a consistent whole from a multitude of inspiring examples? Thus, in addition to the division into thematic units, there was a lack of a curatorial narrative that would communicate more clearly what it was that actually interested the curator in the neighbourhoods. Is this just a survey of imaginations and approaches, or is there a planning change agenda behind it?

An inspiring, perfomative element of the exhibition was the Neighborhood Lab – a workshop space that did not provide concrete examples and solutions, but encouraged speculation on how neighborhoods can be a means for social change. Visitors were invited to respond to more than a hundred prepared tasks: How can we make use of the ruins of the automotive world in a post-automotive age? What formats, events or processes can we create to foster meaningful and productive controversies? What devices can we invent or use to make ourselves better listeners? It is questions like these that have helped to get a good understanding of the breadth and complexity of what is going on in a neighborhood and the politics involved in living in neighborhoods. Thus, this single space, despite its simple architecture and design, stood out from the entire exhibition as a focal point to which one could continually return. It was the only moment where the collective imagination and participation of male and female visitors was enabled. It is just such a moment, however, that requires sensitivity and afterthought – How and who will handle the ideas? Or was it all just “up in the wind”?

Neighborhood lab, photo: Spolka.

Other areas of the museum were filled with, for example, an exhibition of utopian drawings of cities by Peter Cook and the Archigram group. In the context of the other projects, this museum installation in the white cube seemed random. But perhaps these drawings were the tool that allowed us to look at the other projects with a bit of distance – how to depict gradually growing and changing cities or houses? How to blur the distinctions between nature and society? At its core, the traditional format of architectural drawing helped shift the narrative of what we might consider neighborhoods. In the central space of the museum was an overview of current development projects in Oslo – Oslo in the making. Aimed at the local visitor, it was, without the need to reflect on professional practice, an overview of local architectural production or visions for Oslo – a compulsory ride rather than a curated concept.

Coming to the community

Paradoxically, the most interesting part of the whole triennial was the programme, which was developed in collaboration with one of the main partners, the National Museum of Architecture. The opening exhibition of this year’s triennale, entitled ‘Coming to community’, set the bar high for the curious visitor. The museum’s contribution focused on the question of society and exclusion from it – how do loners, queer people, feminists, the elderly and other marginalised groups perceive urban development? Can architecture help create relationships with others?

Coming to community, source: Nasjonalmuseet.

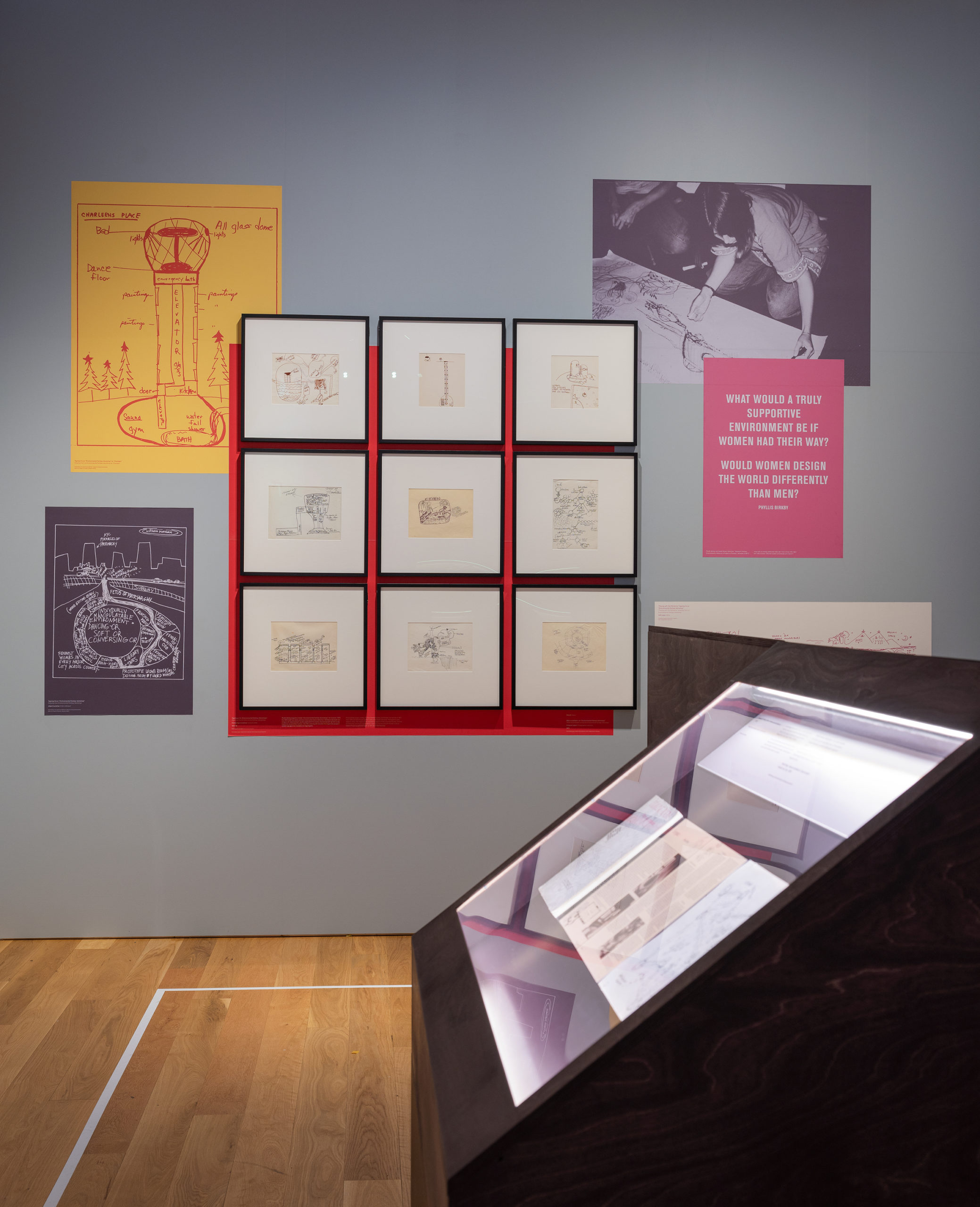

The main tools of communication with the viewer were original texts and manifestos, photographic and drawing documentation from archives, models, a number of sometimes unreadable sketches and records of radical architectural and activist groups from the 1960s to the 1980s. Among them the English feminist collective Matrix, which through archival documentation presented a wide range of work in the field of interdisciplinary critical planning already in the early 1970s.

Another feminist perspective was the work of Phyllis Birkby, founder of both the women’s school of architecture and urbanism, who in the 1970s organized workshops on women’s environmental imagination that allowed for an exploration of what an architecture that also addressed women’s needs might look like. The exhibition also included an installation, The Stonewall Nation, by artist Shille Storihle. Her documentary presented the story of Don Jackson, an American activist who had a utopian vision of establishing a separate city for gay men.

To the question “How can architecture adapt to new forms of community?” a number of theoretical and practical considerations have been put forward, adapted to the challenges of diversity. Both the visual and ideological language of the opening exhibition did not address the question of neighborliness in the classical understanding of the term, but pushed the boundaries of architecture to the painful, often silenced problems of society, still relevant today. The architecture of the exhibition space itself had a clear, even conservative edge, fully balanced by its radical content.

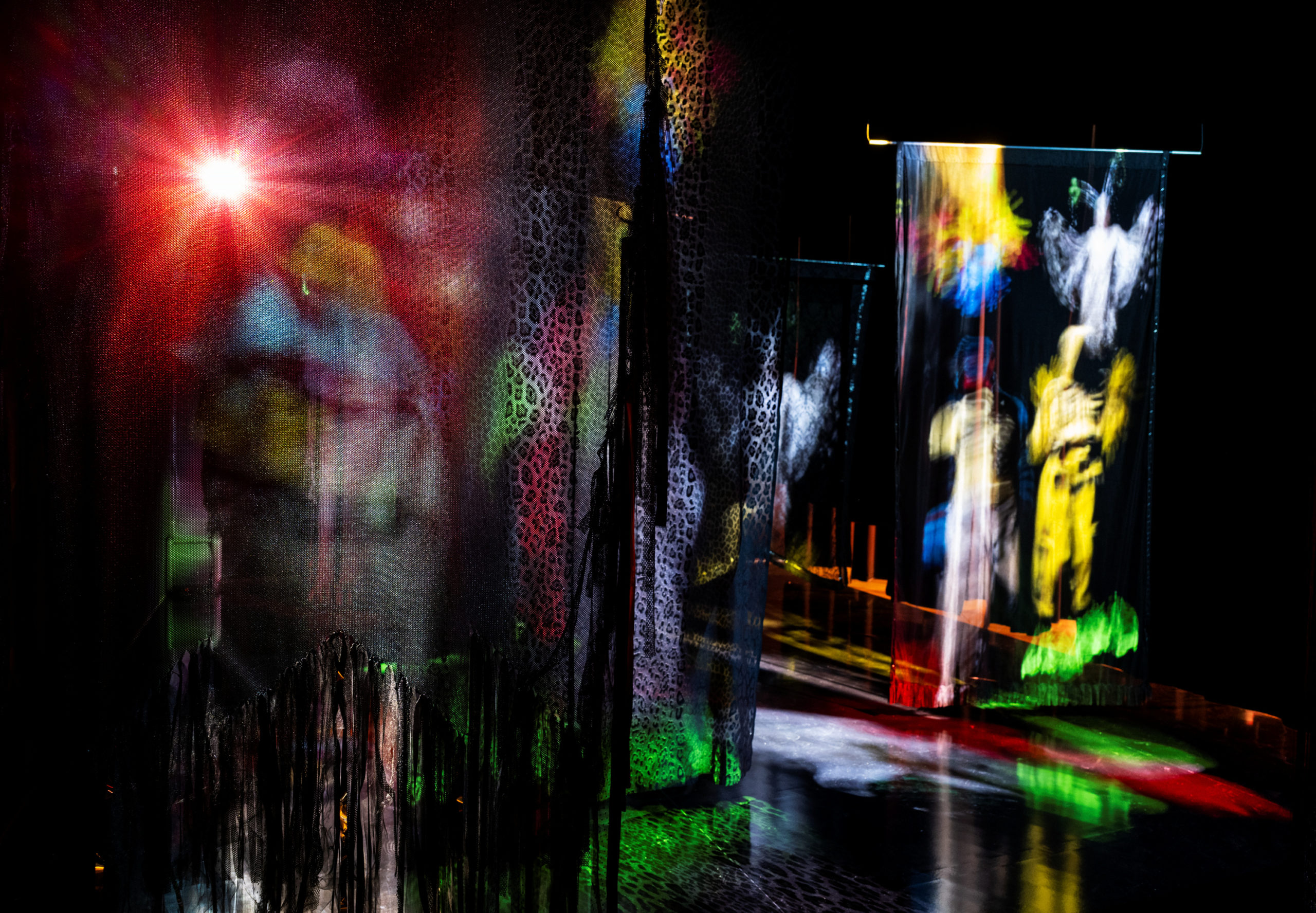

The next venue was the scenographic environment of the art and architecture collective MYCKET under the title Heaven by MYCKET. The importance of community is very palpable and legible here, as the installation referred to the atmosphere of a nightclub – a space friendly to all those seeking relaxation, freedom and fun. For the collective, the idea of finding one’s own community is something that can be connected to time, place and space – architecture becomes a tool to promote diversity. A similarly practical, even surreal, approach to space offers the viewer the opportunity to come to an understanding of how both architecture and design can both support difference and co-create a more tolerant world where there is room for everyone.

Installation Heaven by MYCKET, source: Nasjonalmuseet.

Diversity in practice

Outside the exhibition programme, the Triennial offered the opportunity to attend lectures by personalities reflecting, among other things, the theme of community and diversity. One of them was Jos Boys – a member of the aforementioned Matrix collective. Jos presented the idea of collectivity as they understand it and their activism in the field of design based on community and understanding of everyday social and spatial practices to support disadvantaged groups of society. All of their work explores how we can act across different perspectives and agendas to collectively discuss and improve shared environments.

The next speaker was Joel Sander, founder of JSA/MIXdesign, an architecture studio dedicated to making urban typologies accessible to people of different ages, genders, physical abilities, cultural identities and religions. At the National Museum of Architecture, he presented STUD, a project from the 1980s that explored the male, and particularly gay, experience of public toilets. His current version, the Stalled! project, in turn looked at ways to adapt public toilets and restrooms in public buildings to accommodate different physicalities and disabilities in a broader context.

The need to be in the field

The theme of Oslo’s transformation and growth resonates throughout the city, not just the architectural community. Oslo kommunes kunstsamling, a city institution dedicated to art in public space, regularly supports art projects that reflect the cityscape. That is why their inclusion of the events in the Triennial programme was an appropriate synergy. In collaboration with urban planner Nabib Mackic, choreographer and dancer Mia Habib created a performative project offering the viewer the opportunity to experience the urban terrain of the emerging Økern district through an intensive artistic experience. The first half of the performance took place on a flat, large-scale construction site with many epicentres of action and emerging proto-architectures, later the entire audience and participants moved to a more intimate enclosed site with uneven terrain, where the action culminated in a collaborative deconstruction of the architectonics. The interpretation of the dance work caused the creation of a connection to the space and the neighbourhood, a multitude of scenarios of imagination and manipulation of context. Atmosphere, actual experience, contact and impact – concepts that architecture fabulates/narrates the everyday and that work subconsciously and effectively on the viewer.

Mia Habib, performance in Økern district, photo: Spolka.

The journey is the destination

The trip to Oslo was a comprehensive experience for our collective of the Society. In addition to the exhibitions and the accompanying programme, we visited the gardening colony that supplied Oslo with food during the First World War, the nature parks along the North Sea coast, the contemporary American opera house and gave several talks. All of this together had an impact on the perception of the Triennale. It was one of the experiences of a full week, which was complemented by the more than 60 hours spent on the train and boat we traveled on, in discussions together. And so it is hard to separate it from the rest of the atmosphere.

What is certain, however, is that we appreciated the opportunity to discuss architecture as a social discipline, not excluded from the world of humans and non-humans alike. Instead of technological optimism or formal discussions, the Oslo Triennale turns towards the utility, the everyday and the livability of the city. Themes we would like to open up in the following comments. In fact, with this review, the Society is launching a regular column in which we will bring you more about the livability of the city, how to live in it and how to plan the city through experiences in public space.