Essay / THE MAN FROM DETVA AND BRNO

(Slovenčina) Nábytok a interiéry Dušana Jurkoviča

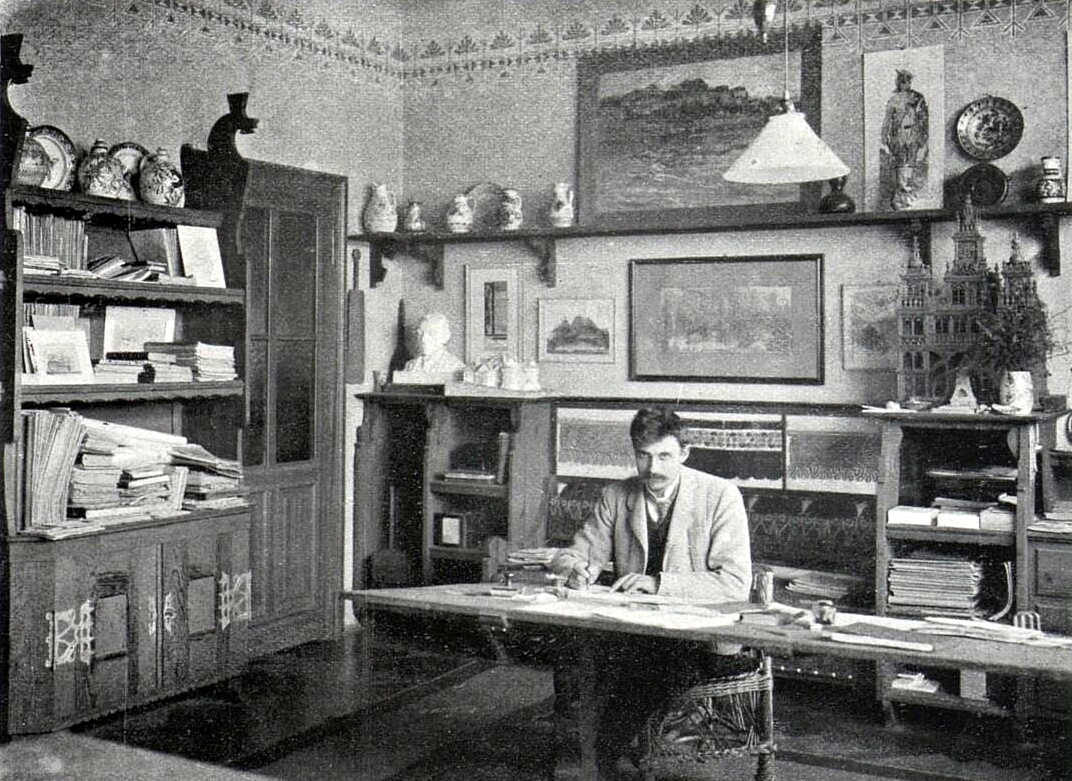

1 Dušan Jurkovič in his study, Veveří 18, Brno, 1905. Repro: Český svět, 1905-1906, vol. 2, no. 2., p. 48.

In 1905, the magazine Český svět published a photograph of a man indoors as part of a special Brno issue. (fig. 1) The man, seated at his desk and diligently taking notes, is a respected member of the Club of Friends of Art, a pro-Brno group of intellectuals and businessmen who wanted to elevate Czech/Moravian identity through consistent cultural and educational work. The man is neither Moravian nor Czech, but in the force field of Slavic sentiment at the time he is a close, if somewhat exotic, “Goral” brother. On the shelves behind him are Modra and other folk ceramics. The sofa is lined with bobbin lace and embroidery, and a traditional wooden washing plunger hangs on the wall. It seems to be someone who is interested in craft artefacts from Hungarian Slovakia. A collector? An ethnographer? Let’s see what else is there. There are several drawings and photographs of architecture hanging on the walls, and there is also a large architectural model. If we squint a little more, some of them are clearly recognizable. There are drawings of the Pustevni on Radhošt’ and their interiors, there is a photograph of the country villa of the factory owner Robert Bartelmus on Rezko. If we guess that the man in the photograph could be an architect, we are not wrong. If we were readers of Český svět, we might have guessed his name too. Because at that time the name of Dušan Jurkovič was already quite well known in Moravia. The architect had been settled there for 15 years and the emancipatory Czech movement had long since discovered Jurkovič’s eminent interest in Carpathian folk architecture and craft and the dreamlike and unmissable way in which he grasped it. The enthusiasm and acrimony that accompanied his work was particularly appealing to the Moravian/Czech nationalists. They described him sensitively, for example, as follows: “Slender man from Detva, rebellious and delicate, with his hard, black face and healthy soul a beautiful type of free, Hungarian Slovak resisting an opression.”[1]

Even the photograph of Jurkovič in the magazine Český svět, although it is not a snapshot, had a quite clear nationalistic intention. Jurkovič appeared here in the context of a discussion of the Club of Friends of Art and the article describes its current position in Brno as follows. “The art of Jurkovič is well known. The architecture is unpretentious but individual and purely artistic, based on works of folk art. He is the builder of Luhačovice and Radhošt’ hostels, those fairy tales of wood and stone! It is unfortunate that he did not build any major works in Brno; here he confined himself to merely arranging the interiors, of which he is a true master.”[2]

By interior arrangement we mean furniture and interior design and we will deal with these in the following text. The time span of our interest is the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and the subject of the study will be mainly furniture pieces that he designed for his Brno apartment at 14 Veveří Street in Brno and are now in the collections of the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava. We will trace how he pursued his creative programme at the time, which one commentator on his work has characterised as a journey from romantic nationalism to aesthetic pragmatism.[3] We will try to show how the national and the international were shaped and intertwined in his work. At the same time, we will try to confront Jurkovič’s version of furniture design with the interior/furniture realisations of authors who, like him, more or less intensively pursued the national, regional aspect in their work and/or considered rural, non-professional architecture and craftsmanship as a point of departure worthy of exploration.

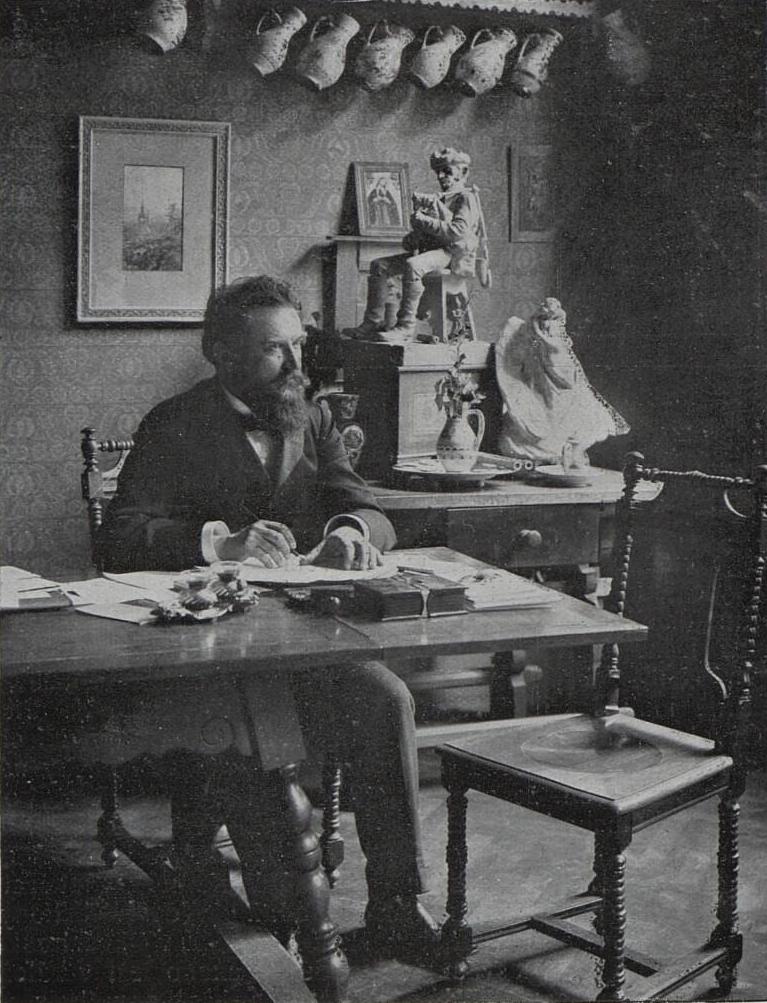

Interiors were the first task Jurkovič received in Brno when he arrived there at the end of 1899 – from Vsetín, where he had previously worked and where he had managed to establish himself as a “specialist in the ancient Slavonic style”[4], he was summoned by František Mareš – an important cultural and pedagogical figure there. (fig. 2) For the girls’ secondary school of the Women’s Educational Union Vesna, of which Mareš was the headmaster, Jurkovič furnished the interiors of its two boarding houses. These are not the first interior realizations – he had previously completely furnished the interiors of his buildings Pustevní na Radhošti (1894-1899), designed furniture for the painter Joža Uprka and in 1899 also designed several realizations for acquaintances from the circle close to the director Mareš.

2 2 František Mareš in his study. Repro: Český svět, 1905-1906, vol. 2, no. 2., p. 48.

Especially the success of Pustevny – a strong ethnographic interest in the saturated buildings of tourist facilities on the mythical Moravian mountain Radhošt’, and also an independent author’s publication about them, opened the gates not only to Brno for him. From Brno he was close to Vienna, which he visited frequently and published extensively in local magazines (e.g. in Der Architekt, later Das Interieur). He probably did not miss the Art Nouveau exhibitions or the legendary The Four with Charles Rennie Mackintosh. He certainly noticed the echoes of the British Arts and Crafts movement in progressive Viennese artists, especially Josef Hoffmann, a Moravian native and already a shooting star of the Viennese art scene at the time, who, like Jurkovič, recognised the regionalist principle (he also collected folk art – he had a collection of Moravian and Slovak embroideries). As Dana Bořutová notes: “The impulses coming from Vienna became the medium accelerating the shift, the beginnings of which could already be seen in Pustevny and which continued in the works for Vesna: Jurkovič gradually moved away from descriptive ethnography, and although he never gave up his predilection for folk art or his pursuit of a distinctive, national expression, new aspects became more pronounced in his work. This is evidenced by works from the early years of the emerging 20th century, especially villa construction and interior design. They show that between 1901 and 1902 Jurkovič was intensively thinking and processing the impulses mediated by Vienna, and this process significantly marked his expression.”[5]

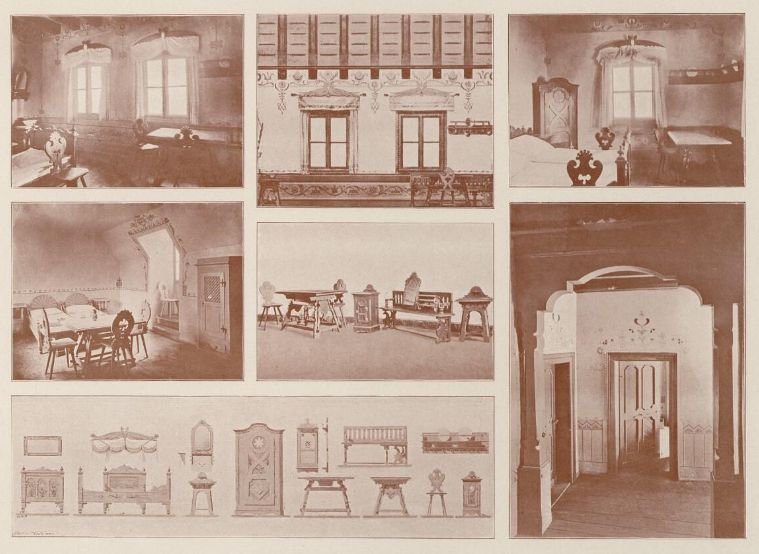

3 Pustevně na Radhošti, design of the interior of the dining room. Repro: Dušan Jurkovič: Pustevně na Radhošti, 1900-1901. fig. IX.

The extremely active Dušan Jurkovič was most intensively engaged in the role of furniture and interior designer in his Brno period – that is, between 1899 and 1918. And although it was not his greatest dream, as it was for many other architects, these smaller jobs were a welcome source of a small but regular income. Because his circle of clients, although very sympathetic to art, was mostly middle-class Bohemian/Moravian intellectuals, but no rich people. He furnished dozens of interiors for them – here he adapted himself flagrantly to the urban milieu and began to dampen the rustic emotion that was his successful trademark at the time with Art Nouveau styling. In terms of materials, he also adapted the furniture more to the needs of the urban customer – better quality wood, the effects of the patterns of several types of wood, stained-glass panels, the involvement of stone.

4 Dušan Jurkovič: Sideboard, 1900-1902, Slovak National Gallery.

In the collections of the Slovak National Gallery there are more than twenty pieces of Jurkovič’s furniture – these are works from the beginnings of his oeuvre as well as works he created at an advanced stage – they are separated by almost forty years. A group of older furniture – from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries was purchased for the collections of the National Gallery of Art from his heirs. They were part of the furnishings of Jurkovič’s own villa on Lermontovova Street. in Bratislava, or were owned by Jurkovič’s sons/ and their relatives. Originally, they were part of the furnishings of the study and bedroom from his own apartment, first at 12 Kounicova Street (applicable to the furnishings of the study) and later at 14 Veveří Street in Brno (the study and bedroom). These are not complete sets, the architect probably kept a few favourite pieces and they travelled with him to all his addresses. Probably for nostalgic rather than practical reasons. The architect designed the interior furnishings at both of these addresses – he occupied the first, still bachelor apartment at 36 Giskstrasse (now 12 Kounicova Street) from 1899, just after he moved to Brno, until about 1903/1904. The photograph of the study probably comes from this apartment, where the furniture he preferred for the needs of his studio also appears for the first time later. So perhaps these pieces were made around 1899, although the designs for this furniture in his estate at Slovak National Archive date back to 1902. The rendering, the folk zoomorphic motif rethought and rendered in the form of a distinctive spatial accent, the calm, restrained silhouette and the subtle surface ornament would suggest a somewhat more mature phase in the handling of folk design – the historicizingly exuberant epicism of, for example, the Pustevní furniture seems here to be calmed and purified in favour of concentrating on just a few emphatic and characteristic elements.

5 Dušan Samuel Jurkovič: Cupboard, 1900-1902, Slovak National Gallery.

Anyway, a few years later we have more information – Jurkovič had already got married and moved into a new building, which in the meantime had grown up a street away, at Veveří 14. The four-storey tenement house was built between 1901 and 1903 by one of Brno’s most prolific builders, Franz Pawlu. Jurkovič moved into what was apparently already a larger apartment, designing furnishings for his study, dining room and bedroom.

6 Dušan Jurkovič: Library. Own flat, study – Veveří 14, Brno , 1899 – 1902, Slovak National Gallery.

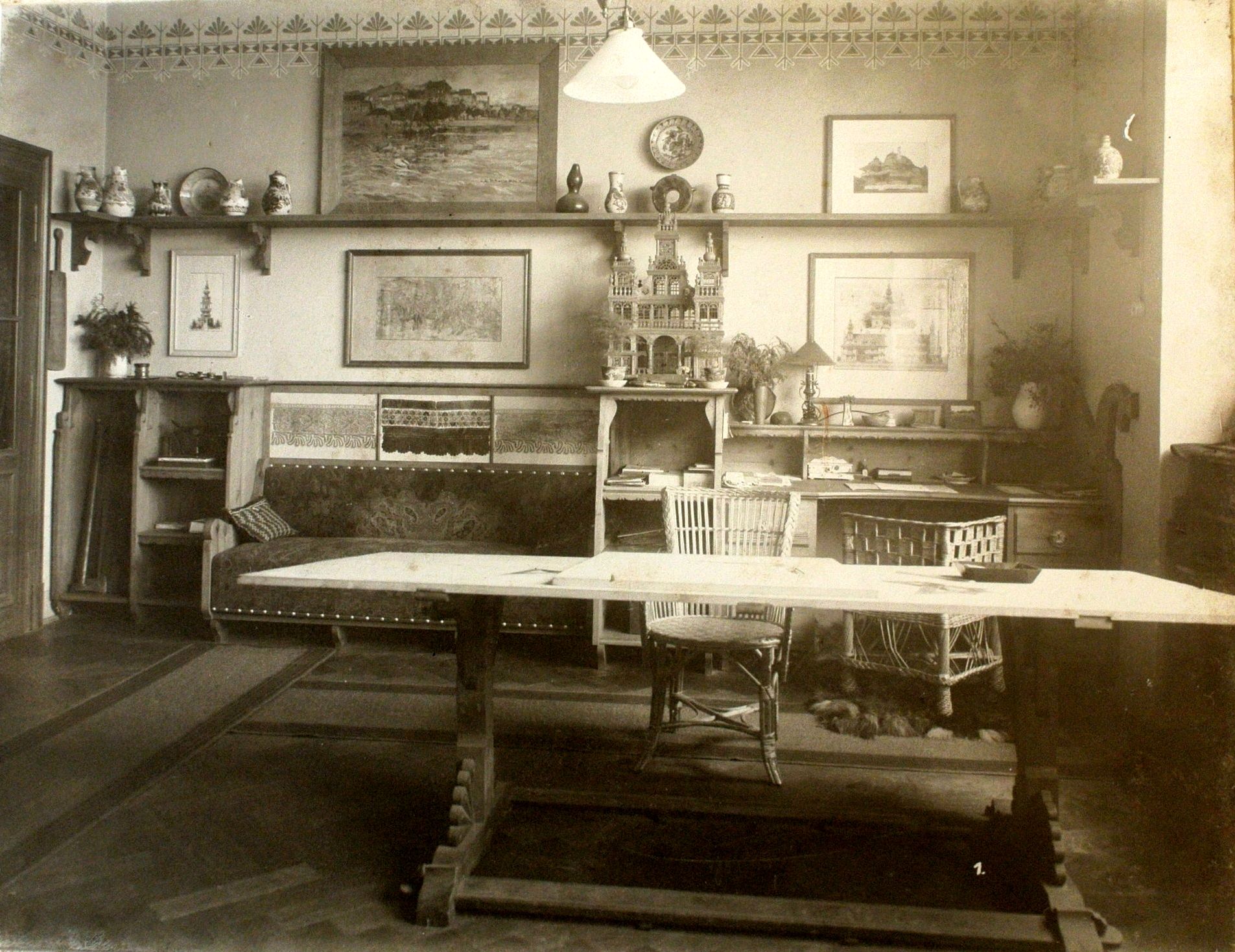

7 Dušan Jurkovič’s study, Veveří 18, Brno, 1902. Repro: ŽÁKAVEC, František. Dílo Dušana Jurkoviče. Kus dějin československé architektury. Prague: Vesmír, 1929, Annex I.

The furnishing of the study – high and low library shelves can also be seen in the photograph from Český svět (fig. 1) Jurkovič furnished many flats in his circle of acquaintances and probably also on the basis of related requests from similarly disposed clients or directly on the basis of a request such as “I would like furniture like the one Mr. Mareš has”, he created several interiors with similarly designed furniture. He adapted the colour scheme, the type of materials used, the composition and the arrangement of types. But he did not have these worries when furnishing his own office. His study is unpretentious; the furniture already bears specific elements of the artistic fusion of his tireless ethnographic research and Art Nouveau instruction. Zoomorphic decor – profiles of animal/horse heads with crowned manes top the library display cases and form the grip of the wall shelves. An identical – fairy-tale or real creature appears in 1899 on the design of the unrealised Svetozor summer palace. They are such inconspicuous drawings on the side of a leaf, but Jurkovič probably liked them. In the case of the tall library, Jurkovič managed to design a very convincing example of “revived” furniture. He unorthodoxly displaced the cut decor into the space and gave it the function of a distinctive, peculiar accent. He supported his regionalist attitude only with unobtrusive arch carving, and accentuated the modernist reduction with Art Nouveau-style fittings and a combination of wood cuts. And in typical Jurkovich fashion, he also took care to support his concept with colour – here it is green staining. The room is furnished with mostly open shelving units, lined up almost along the entire perimeter of the room. Between them, desks or a sofa are nested intactly. A logical, regular scheme can be seen in the horizontal division – materially lightened towards the top by a continuous shelf band and finished with a painted Art Nouveau bordure. The spatial landmark is a fold-out work desk (we know, as we know the room plans, that there were two) with a massive throne with a motif of a stylized peacock/dove’s tail, or if you prefer a fan. It is as if here, in the pragmatic and elemental nature of the articulation, he is referring to both vernacular ‘world-rooms’ and modernist orthogonal construction. It is not, however, an interior of the Hoffmann type, where everything is subordinated to the idea of the gesamtkunstwerk. In fact, the seating furniture he chose was industrially produced. Here and later in several interiors, for example in the exhibition halls for the Friends of Art Club, it was the light wicker armchairs. It was clearly an engaged living space, clearly communicating the professional, national and aesthetic status of its owner. It was a functional design office, a showroom, and the dwelling of a collector and art lover all rolled into one.

8 Dušan Jurkovič: Bed, 1900-1902, Slovak National Gallery.

In other rooms, which you for an apartment on Veveří ul. 14, we also read subtle echoes of floral Art Nouveau. For example, in the supple curves of the sideboards from the dining room or bedroom, these still retain a slight inclination towards the eclectic articulation of the design. The immediate predecessor of the upholstered sofa with an extension from the study can be found in Blazej Bulla’s Altdeutsch, architecturally designed sofa from the 1890s.6 But Jurkovič’s inspiration from Bulla’s attempt at a vernacular style is most clearly manifested in his preference for a fan-shaped/radial motif, an emblematic element of his furniture manuscript at the turn of the century. It suited him both in its straightforward symbolism and its striking visual impact. He applied it in many ways as a small decorative detail, for example in the case of his own bedroom, but also as a supporting structural element of beds or bedside tables. This type appeared in the interiors of the villas on the Rezko, in Vesna, and he may have had it in his bedroom on Veveří ul. 14. In any case, he transferred it to his villa in Bratislava. It is typical of Jurkovič in this period that he put an accent on imaginative and sujet-motivating elements. Such a message is conveyed, for example, by the unobtrusive drawing of engraved and burnt ornament, one could call it a proto-version of narrative/emotional design. This is not Viennese sophisticated refinement, but neither is it a Witkiewicz or Brzegian paraphrase. It has the parameters of a focused and deliberate abstraction and reduction towards the construction of a convincing ‘pratvar’. The experiment of searching for a new, authentic form is undertaken from the pragmatic position of fulfilling the ambition of a talented and self-confident creator, which is why, as a young builder, he chose the more favourable professional environment of the Moravian town of Vsetín over his home, but infertile ground for building tasks. At the same time, in the Moravian milieu, imbued with Slavic traditions, he was able to develop his integral passion for folk culture, which for him also has the charm of a true, authentic gesture. No one had to convince him of this, and unlike, for example, Ján Kotěru, who looked at folk art with an academic eye and for him it was actually just an episode, Jurkovič’s deep ethnographic interest never left him. It was for him, familiar with the vibrant metropolitan Vienna during his studies, a trace of home, which he already looked at with different eyes, but at the same time he discovered a fairy-tale childhood in it. As Pavel Zatloukal notes, “He is not alone in trying to evoke such a ‘lost paradise’. More such boys, who as grown men tried to treat the world in a modern way and at the same time offer it a fairy tale of the childlike security of a rural home, began to move around in Central Europe. At the same time that Picasso was discovering black masks in the Paris flea market, Jurkovič was discovering Carpathian folk architecture. In both cases, these were areas that defied conventional notions of the boundaries of culture and civilization.”[7]

10 Dušan Jurkovič: Chair, 1900-1902, Slovak National Gallery.

On the Polish side of the Tatra Mountains another project, imbued with a strong national romanticism, was created at the end of the 19th century – it was signed by the Lithuanian-born architect, designer, painter, writer and critic Stanislaw Witkiewicz. The comparison between Jurkovič and Witkiewicz, due to their common Carpathian background, was already offered in the contemporary perception of their work, but the motivations are quite different now. According to some scholars, Witkiewicz tended towards an “isolated, exclusive, ‘Zakopane architecture'”, seeing it as a preserved relic of the architecture of the Prapolis. In contrast, Jurkovič understood the Carpathian region and its building tradition as homogeneous, and his conception of “national architecture” in this sense was inclusive, based on a broad register of close regional influences.”[8] The Polish attempt at a national style, underpinned by an entire art-mystical theory of national being based on a mythological folk culture, had particularly broad regional support. Zakopane was then being extensively rebuilt in the Highlander style. Zakopane-style ceramics and furniture were sold all over Poland, although Witkiewicz’s dream of promoting the Zakopane style on a Polish-wide scale did not come true.

But we will now notice more the “Zakopane style” in the interior, furniture solutions, in the villas in Zakopane designed by Witkiewicz. Witkiewicz, who appeared in this Tatra resort from 1890 and articulated the theoretical basis of the style in several treatises, entered the local carving and furniture-making scene by criticizing its leading representatives. In Zakopane there was the Fachschule für Holzarbeitung in Zakopane, which produced furniture accentuating from the 1880s onwards the sub-Halanian decorative patterns. Depending on who was the director, the styling apparatus also differed – the eclectic grove mixed Tyrolean, Halic and Zakopane patterns. Witkiewicz rejected all of this, pointing to the potency of the Highland building and craft tradition. He based the concept on the construction type of the Highlander hut, and he also modelled it on Highlander folk art and craft. Wikiewicz, like Jurkovič, consciously used rather than imitated the vernacular, but in the name of the new Polish art he gravitated towards soaring and pathetic paraphrases. His convention was a repetitive, almost manifesto-like ornament, imbued, according to him, with an authentic “Highlander”. He preserved the character of an all-wooden building also in the interior, the constructive element on which, according to his own words, he emphasised, was abundantly supported by the carved decor applied throughout, in which he alternated sub-Halanian geometric and floral ornamentation, extended by motifs of the Tatra flora. The repertoire of furniture inspirations included traditional tables, chairs, shelves, chests, trunks, trunks, he recommended to look into “stylish motifs” in case of a need for modern furniture type. He thus motivated customers and especially co-workers to compose new home furnishing components from various household objects and furniture, e.g. a sledge could become a template for an armchair. The opulent ethnographic-eclectic vernacular of Jurkovič’s Mamněnka is probably the closest to Witkiewicz’s outlook, and Witkiewicz’s interiors kept this character constant. They did not, however, have Jurkovich’s ability to hatch and convert visual motifs with panache, his imaginative or synthesizing bravura. His interiors and furniture thus remain somewhat lifeless, the staged, museum-like character lent to them by the almost obsessive emphasis on wood and the ubiquitous cut décor. Wiktiewicz, with his Zakopane lectures, provided a particularly strong ideological base for the developing Polish emancipation movement, and became known as a skilled promoter of the Polonization of domestic culture. This is confirmed, after all, by the words of Wojciech Brzeg, perhaps the most talented furniture designer from Zakopane, who often collaborated with Witkiewicz: “I believed in Witkiewicz. I felt it was the duty of a Pole and a highlander to work in this way. I therefore dedicated my life to furniture in the Zakopane style.”[9]

11 Wojciech Brzega: Table from Villa Pod Jedľami, circa 1902, source: wikipedia.

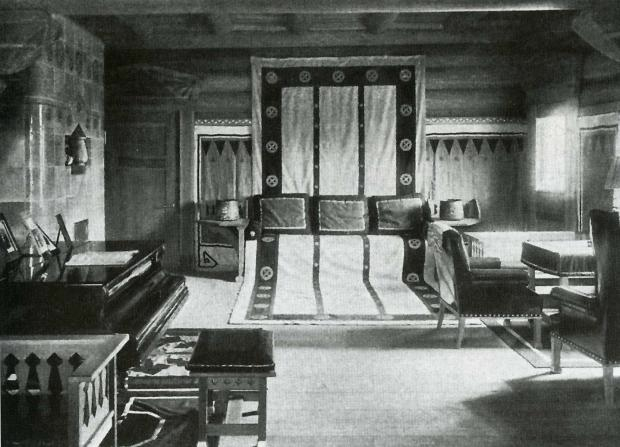

More than a thousand kilometres to the east, the leader of the St Petersburg Art Nouveau movement, Roman Fyodorovich Meltzer, offered his creative manifesto as a neo-romantic feria. This Russian-German from St. Petersburg, architect and co-owner of a furniture factory (incidentally still in operation today), built his own villa on St. Petersburg’s Stone Island between 1901 and 1904, whose exterior and interior he ran through a related fantasy filter as Jurkovich. From the outside, Meltzer’s villa is almost grotesque in its insistent expressiveness, and as disjointed as Baby Yaga’s cottage. After all, that’s what the St Petersburgers nicknamed her. But what he shares with Jurkovič is a talent for formulating original and modern form through unorthodox means – in Meltzer’s case, Russian and Scandinavian vernacular architecture; his villa’s exterior is somewhat halfway between Jurkovič’s Bartelmus resort on the Rezko and his own villa in Brno-Zabovřesky. Melzer was able to synthesize the folkloric traditions of neighboring ethnic groups and transform them into a distinctive poetic image with an emotionally saturated interior environment. He also designed the entire interior furnishings, the furniture was of course made by his father’s company. We can only partially reconstruct exactly what it looked like today based on a few black and white photographs, as the facility was not preserved after modifications in the 1920s and 1970s. The internal organisation of the building was characterised by a flexible interconnection of rooms and a smooth flow of space. The ground floor had concrete vaults, while the walls and ceilings of the 2nd floor, in turn, were chosen by the architect to be made of sturdy pieces of logs in order to support the earthy character of the dwelling. Eccentrically placed, crossed logs dynamise the space, visually and structurally define it, and are also a kind of non-conforming type of decor. Conventional ornament does appear here, but as a carefully transposed detail, often projected into a constructive position, not dissimilar to a Jurkovich fan The arrangement of the interiors, organically unified by built-in furniture, bay-window niches and simple, comfortable armchairs, refers to the English style of country living. Glass stained-glass windows appear to be powered by secession, while rudimentary geometrically composed textiles referring to Scandinavian ornamentation appear in one of the main living spaces, used as an area (and perhaps) colour accent in a Byzantine or medieval manner. The central textile, in its function as both wall decoration and carpet in one, is in turn a version of the traditional Finnish tapestry or woven carpet called ryijy, made famous by the Finnish painter Akseli Gallén-Kallela in an iconic Art Nouveau version just a year before construction of Melzer’s villa began.The carpet, called Flame, was first presented at the Paris World Exhibition and later donated to the architect Eliel Saarinen.The latter made it the dominant feature of the living room in his own home and studio in Hvitträsk, perhaps Finland’s most famous national-romantic villa.But Hvitträsk is also interesting for its parallels with Jurkovič, especially with his own Brno villa.But that is beyond the scope of our story.In any case, we find Finnish folk and Hvitträskovian in Meltzer’s villa in multiple ways – in the burgundy ornaments on the fabrics and the log paneling.For the Finns, who at the time were struggling with the growing influence of the tsarist empire and the threat of losing their autonomy, this might have been a kind of satisfaction.

12 Roman F. Melzer: Interior of his own villa on Kamenný ostrov, 1901-1904.

The Hungarians, who, like the Czechs, Slovaks and Poles fighting for self-determination in the spirit of the pan-European reformist artistic movement, paid intense attention to original folk art, could certainly feel themselves as a nation on the rise around 1900. Unlike them, however, they also had official support for this movement, but this did not mean that they did not have to define themselves against the prevailing German influence. Cultivated with love and enthusiasm, Hungarian history did not miss any opportunity for research. The search for the Hungarian national style was a very promising option in this respect. The migratory and ever new impulses-fed excursion about the mythical homeland of the Ugric people generated a number of exotic destinations, and this is also why various oriental/eastern influences appeared in the source code of e.g. Ödön Lechner. But if we restrict ourselves to more accessible inspirations, the hotbed of rural Hungarian culture could have been the Kalocsa of Transylvania and its peasant craftsmanship and architecture, or the traditional culture of the Szekely or Hucul regions. And as a Hungarian example of the clash between the national and the international, overlaid with even more nationality in the exterior, we can look to the realisation of Ödön Faragó – one of Budapest’s most successful furniture designers. He received a very prominent commission in 1897-8. For the Empress of Austria and Queen Elisabeth of Hungary he had furniture for a garden house at Buda Castle. The exterior and interior were designed by Alajos Hauszmann (the architect who rebuilt the castle complex at that time) and although it was to be Magyar Ház, from the outside it was more evocative of an Alpine mountain hut. This is what the surviving photograph of the interior offers us, as well as the existing fragments of the original furnishings.10 Because today we can no longer find this “modest tribute” to the beloved “magyar kiraiylné” at Várkert. The house was destroyed during World War II. A copy of the collection of furniture from its interiors is now in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Faragó was instructed to design not quite a living space, but a kind of resting area, a kind of quiet place in the lee of the bustling and then extensively reconstructed Buda Castle. At first glance, the space looks a bit clueless, especially with the randomly arranged furniture (which was not customary at the time). However, we do not know if this is the definitive version. In any case, the promise to create a Hungarian peasant’s room for Elizabeth was realised first with an effective wall and ceiling layout. He tied the calm, sober strip of wood panelling, forming a horizontal band around the entire room, by creating a large-scale geometric grid, which he filled with a striking floral ornament in some places and developed with an abstracted tree/plant motif in others. The national note is clearly played here precisely by accentuating the richness and apparently full-blooded colour of the exuberant floral flourishes, referring perhaps to the decoration of the peasant cottages of Transylvania (framing the door frame with an ornament in the manner of a traditional jujube) or the costumes of Kaloc.[11] In this realisation, Faragó superimposed the then growing ethnic demarcation onto the geometric plan already understood in the Art Nouveau style. The subtle and nervous curves of Floral Art Nouveau, which he favoured (in Hungary not only), the Sikh ornament in the impressive carving and perhaps also traces of elements of Neo-Rococo and Empire characterise the furniture furnishings, of which the seating types in particular are worth a closer look. Here Faragó has reached for a unique take on traditional craftsmanship. He “interlaced” the wooden backrest with strips of beaten leather, thus harmonising the silhouette of the furniture and giving it a modern expression. Here, like Jurkovič, Faragó was able to think empathetically and artistically boldly, he did not abandon the concentration on ornament, but uncovered a new layer where rustic leather, brightly accented with brass, plays the role, not in a primordial way. Finally, the shape of the chairs and some armchairs – seating furniture designed for the private apartment of František Mareš in 1902 – also reminds us of Jurkovič’s solutions.

13 Interior of a Hungarian garden house and furniture collection by Ödön Faragó, 1897 – 1902. Repro: GÁL, Vilmos. Sissy sosem látott bútorai. In: Magyar Asztalos-és Faipar, 2009, no. 12, pp. 99-101.

As several scholars have noted, the lore of Carpathian traditional architecture and craftsmanship has permeated, to a greater or lesser extent, the revitalizing artistic efforts of all ethnic groups living in the Carpathian arc. We have seen it in Jurkovič, Witkiewicz, Brzeg and Faragó, we could find it in Kotěru, Hoffmann and several others. In the same way, we can trace in all of them the tensions that accompanied a very artistically eruptive period. We could notice how quickly, from year to year, influences and models entered the artistic programs of talented and capable creators.

Jurkovič was undeniably one of them. His method was flexible and sensitively related to the specific assignment; it could be a complexly designed interior work as well as Loos-style individualism. He knew how to be assertive and practical, but he did not give up following international events, activism and juvenile dreams. As Matúš Dulla aptly summed it up: “In him, an inner conviction and enthusiasm seemed to emanate from his creations, a pantheistic spirit that, according to Tomáš Štraus, transcends the material determinism of architecture.”[12]