Essay / Miloš Laky (1948 – 1975)

A biographical sketch and contribution to the social history of the Slovak neo-avant-garde in the early 1970s.

Among the systemic signs of the coming normalisation after 1968 in Czechoslovakia is the comeback of censorship, tightened ideological surveillance as well as the State Security’s (ŠtB) newly discovered interest in the artistic scene.

Normalisation and the End of Avant-garde

Even though the ideological canon of the times (Lessons from the Crisis Developments, 1970) does not mention artists directly, as normalisation aesthetician Pavol Paška in his work Historical Lessons for the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPC) and Culture put it: „The lessons must be linked with the direct suggestion of the 14th Congress of CPC that bestowed very serious tasks upon the whole of the artistic front in connection with socialist realism.” The effects of the return to talks of socialist realism on the emerging (neo) avant-garde Slovak visual scene that managed to partially establish itself also internationally in the late 1960s, were disastrous.

For a long time, the last official international exhibitions in which a strong generation of Slovak and Czech artists could participate after 1968 were the Venice Biennale in 1970 (with the exhibition of Jozef Jankovič) and the World EXPO exhibition in Osaka, Japan, with the participation of Stano Filko, Jozef Jankovič, Karel Malich, Stanislav Kolíbal, Milan Dobeš etc., where the Czechoslovak pavilion even won the prestigious award for the best design.

Although member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia Bohuslav Chňoupek, the later minister of foreign affairs, upon attending the pavilion, promised the involved artists state prizes for their dignified presentation, what awaited them in reality was disparagement and persecutions. In March 1971, artists Jan Krejčí and Oldřich Kulhánek were taken into custody for alleged sedition and defamation of the republic. The general commissioner of the exhibition, Miroslav Galušek, and his two assistants (Koudelka, Košt’a) were indicted on trumped-up charges, and the trials dragged on for the next five years.

Jozef Jankovič’s exhibition in Venice came to a similar political end. Jozef Jankovič put a monumental “trampling” relief in the colours of the Czechoslovak flag on the ground right near the entrance. However, at some point Soviet minister of culture Jekaterina Furtseva visited the pavilion and after seeing the Jankovič’s “flag on the ground”, she is said to inquire of her Slovak colleague comrade Miroslav Válek whether this was not a covert way of the artist commenting on the destiny of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. This affair contributed to the Jankovič’s later expulsion from the Union of Slovak Artists.

In this ambivalent atmosphere, Miloš Laky, a young talented artist, studies at the Bratislava’s Academy of Fine Arts and Design (AFAD) between 1968 and 1974.

Miloš Laky „Popular in a Collective“

According to the memories of friends, he was a good chess player and athlete (he ran a marathon as part of a bet), and he could play the violin and the accordion. In his youth he had a tragic life experience when his father was killed in a car accident and he lost an eye.

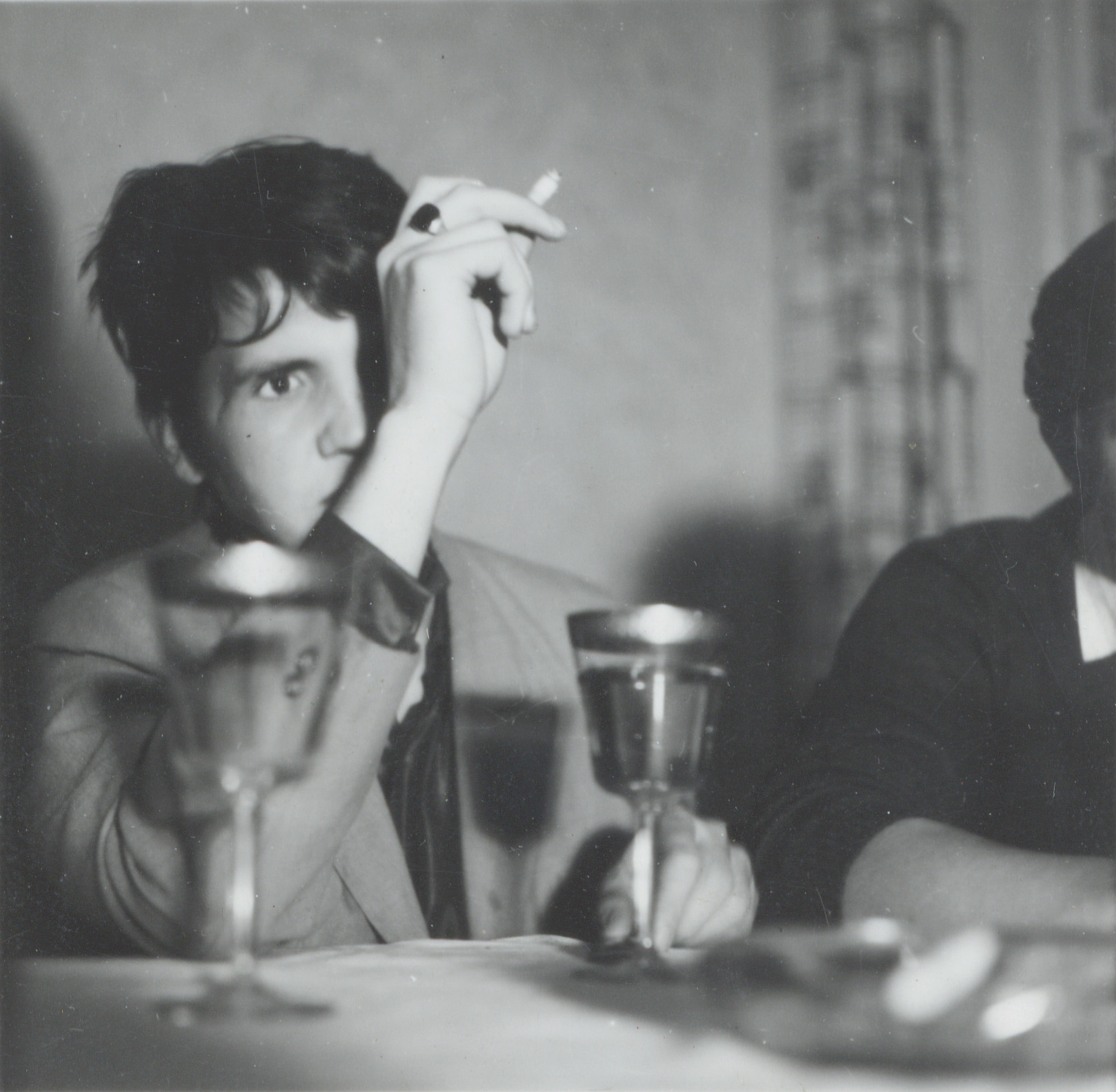

Miloš Laky, around 1969. Photo: Ľubomír Ďurček.

In the first year, in addition to school, Laky could form his own views on art at important exhibitions such as Danuvius ’68; the key works of American abstraction from the MoMA collection (Kooning, Lichtenstein, Pollock, Rothko, Rauschenberg, Warhol, etc.) could be seen in the Slovak National Gallery of Art within the exhibition titled Painting in the United States after 1945: Disappearance and Reappearance of the Image at the beginning of 1969. Its European tour in the late 1960s was organised and funded by Americans (probably as part of active CIA measures in the cultural area). At that time a breakthrough selection of texts by Kazimir Malevich in the Slovak translation of art and literary theoretician Oskar Čepan comes out and Laky studies it with his classmate Ján Zavarský.

From 1970, however, the situation deteriorates rapidly. Part of the emerging generation of Slovak artists and theoreticians found themselves outside the official structures and under the surveillance of the secret police as a result of the coming normalisation. The reaction to the clampdown was a certain consolidation of the Bratislava artistic community and the de facto emergence of an unofficial scene. As early as November 1970, the legendary exhibition titled Open Studio took place in the private home of artist Rudo Sikora.

The regime’s pressure resulted in more private meetings and a strengthening of the collective spirit. In this way, the regime, as a common enemy, brought together even those artists who, under normal conditions, would probably have found it difficult to find a common artistic language – when, for example, Koller, Bartoš or Ďurček, with their discreet, “anti-artistic” approach to the concept, were more of a counterpoint to the generous, almost theatrical forms of presentation of Mlynárčik or Filko.

Open Studio, 1970 (Viliam Jakubík – Vladimír Kordoš – Marián Mudroch: Manicured Flowerbed).

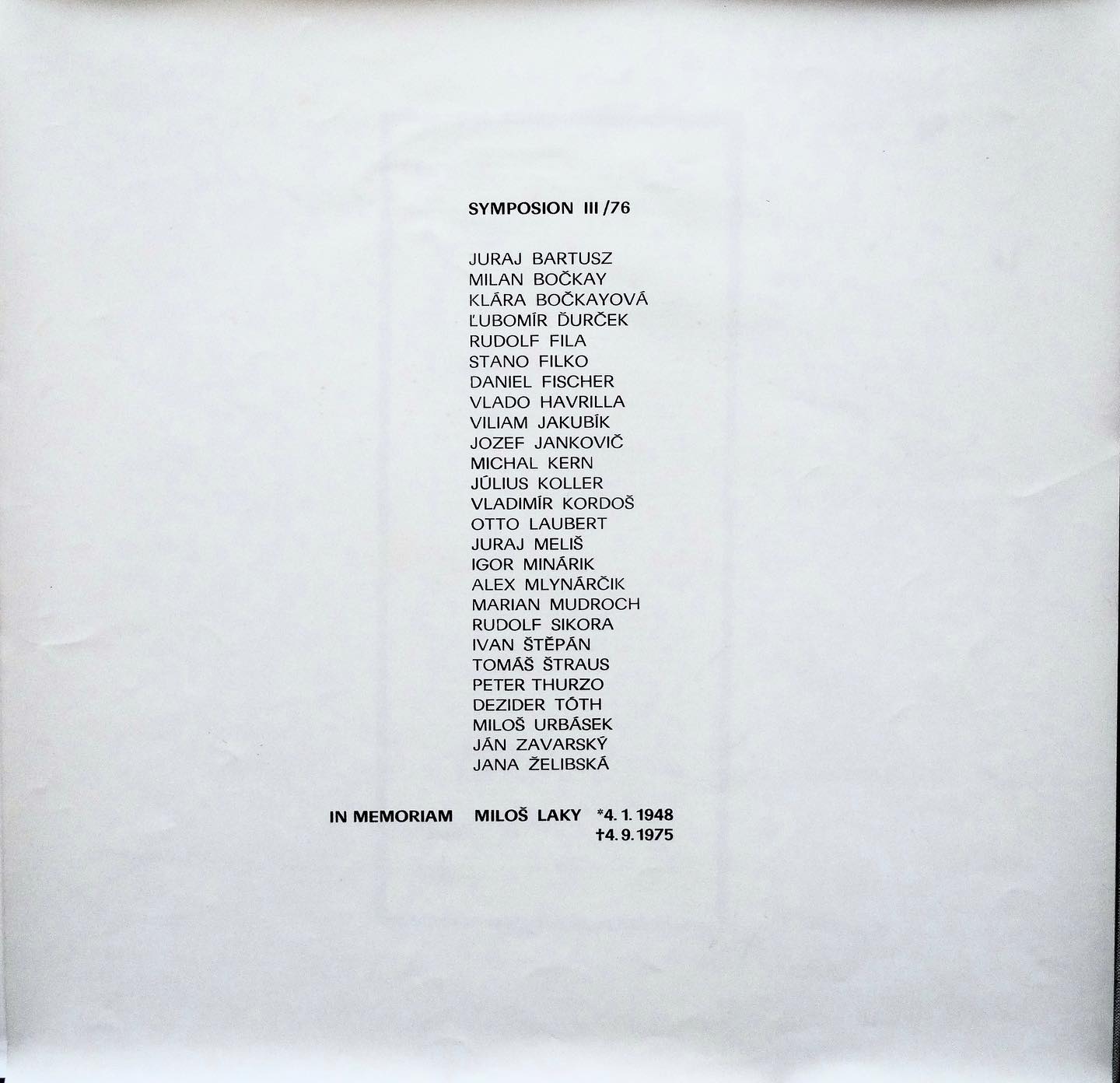

One of the important figures in this company is Miloš Laky, a student who enters the scene together with Ján Zavarský. Virtually all of Laky’s friends agree that he was a man of exceptional qualities and talent, and they also agree on the unobtrusive but important initiatory role he played in this particular period of Slovak art. He used to speak of art as something „to be invented“, not necessarily „to be created“. Symposion III (In memoriam Miloš Laky, 1976), the commemorative album which includes works by almost all the relevant figures of the unofficial scene of the time, is also an expression of respect for Laky.

The list of authors in the Symposion III/76 album.

In art history, his name is mostly mentioned in parentheses in the set with other names. Already during his college days, he made independent art together with Ján Zavarský, both of them passing through different groups of authors. First, in the Time I and Time II projects (Bartoš, Filko, Kern, Koller, Laky, Sikora, Štraus, Zavarský), they searched for parallels between art and science. From this period, Laky‘s estate has preserved a separate text entitled Ideal Future which contains 52 diagnoses/prognoses for the development of humanity (up to the idea of the gradual extinction of the homo sapiens species as a result of human intimate involvement with cosmic beings) in the form of aphorisms or maxims revealing Laky’s civilisational optimism based on his belief in the symbiosis of art and science, on the merging of power and truth, etc.

„The society will do without religion. Faith will persist.”

“The year 2000 will be an interim period when the majority of workers will think in mathematic terms.”

Cosmic Messages and Štraus vs Matuštík Dispute

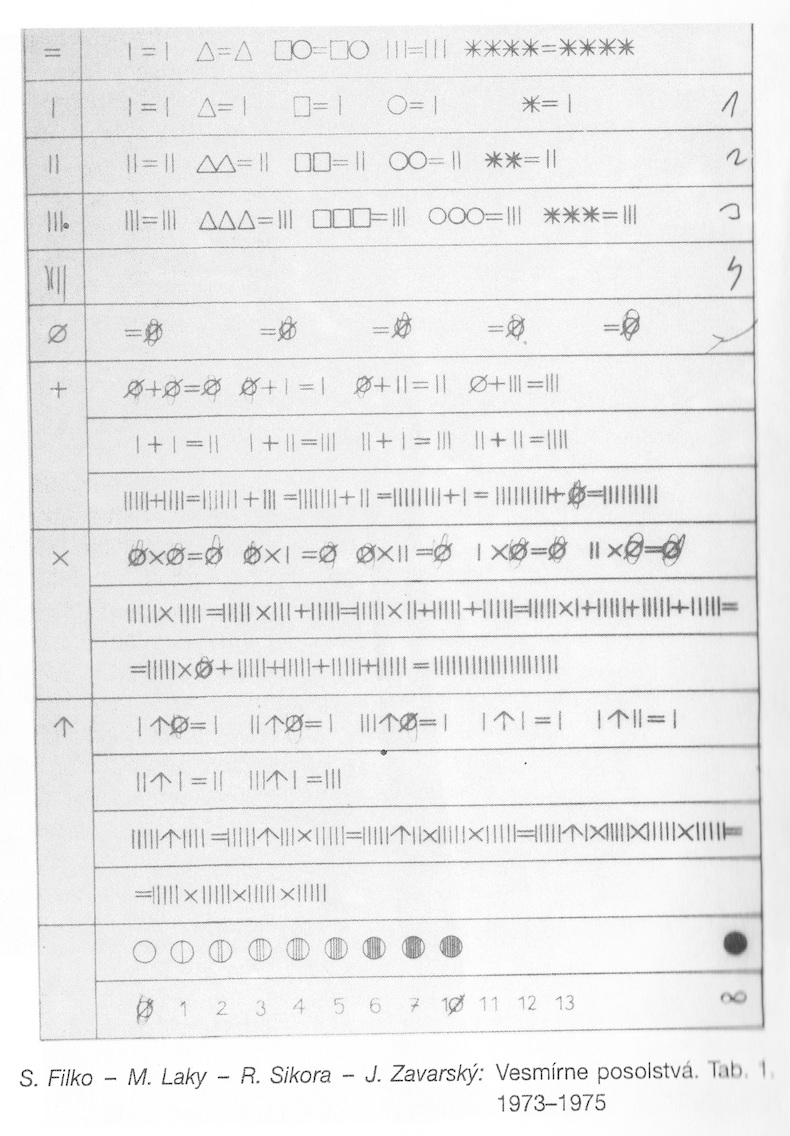

The culmination of these efforts was an attempt by a part of the group (Filko, Laky, Zavarský, Sikora) to formulate an intergalactic message to extraterrestrial civilisations in the work Cosmic Messages (1973-75), which was inspired by the project of American astronomer Carl Sagan. The Sagan’s plaques depicting the figures of a man and a woman sent by NASA into space with the Pioneer probe sparked a negative reaction of the Bratislava group and so they came up with their own, much more radical proposal on how to address extraterrestrials better.

An extensive plan of ten plaques was devised to carry visually encoded solutions to fundamental scientific and philosophical problems (1. Number, 2. Counting, 3. Area, 4. Space, 5. The Standard of Time, 6. Length – the light-year and day, 7. The position of the Sun in the galaxy, 8. The position of the Earth in the solar system, 9. The Earth, and 10. Relativity), but this soon proved to be too ambitious. In this context, one of the invited scientists, physicist Ján Pišút mentions that „the message to be engraved on a small durable metal plaque was discussed somewhere near Búdková street (editor’s note: in the Stano Filko’s flat on Na Hrebienku street in Bratislava). As physicists, we proposed to include the information about the spectral lines of the simplest atom, the hydrogen atom, or about the energy levels of this atom. The ratios of the lengths of spectral lines (or the energies of energy levels) would be easily represented by line segments of the length with the same ratios as the length of spectral lines. We wondered for a long time about how to encode the absolute values of the length of spectral lines of the hydrogen atom on the plaque, but we didn’t arrive at any definite end.“

Only a fragment of the grand plan has survived. It was published in Tomáš Štraus’s book The Slovak Variant of Modernism, and thanks to this we can see that a group of artists managed to come up with a quite interesting visual solution of the first two problems (What is number and counting?) in the form of an original iconic transcription of basic arithmetic axioms using a few universal signs such as: I, 0, =, . In the simple tabular sketch we can see and “read” a peculiar representation of the definition of the equation (=), significant element (number 0), the definition of the successor (+1) along with the rules of commutativity of addition and multiplication.

In: Tomáš Štraus: The Slovak Variant of Modernism, p. 264.

The use of I and 0 signs for the coded transcription of the so-called Peano axioms led the court art historian of the Slovak conceptualists, Tomáš Štraus, to a superficial interpretation of the work, according to which “it is a transformation of mathematics from decimal system to the more general and simpler binary system.” Such a misguided interpretation was already noticed by Radislav Matuštík in his review published serially in the Profil journal for contemporary art (volume 1993). In a devastating critique of the above-mentioned Štraus’s book, he literally ridicules the author, calling him an “uninformed enthusiast”.

“It would be hard for you to explain how the binary number system is simpler,” writes Matuštík, giving his colleague an exercise in converting binary numbers to decimal numbers (he gives the number 110101010101101). “If you get it right, you will get a five-digit number that is related to your friend,” concludes Matuštík. If we do this exercise, we get the number 27309. It is clear from the context that Matuštík is using this exercise to refer to the registration number of the State Security (ŠtB) file kept on Štraus’s friend, the artist Juraj Mihálik, who touched upon the circumstances of his cooperation with ŠtB in his memoirs published that year (Memories of Failures, 1993). Matuštík is apparently alluding here to the fact that Tomáš Štraus himself had been a registered agent of ŠtB under the code name “Tomáš” since 1973.

Filko Meeting Laky and Zavarský

While Laky and Zavarský live a student life in the early 1970s, the eldest of the trio, Filko, suffers existentially. His promising international career is impossible after 1968. He is expelled from the Union of Visual Artists, and despite his continued interest in collaborations on the unofficial scene, several of his colleagues insist on his non-attendance at Sikora’s Open Studio. At this time, he develops collective projects, as he says, in order “not to fall into deep individualism, into isolation, into introvertedness.”

By encountering Miloš Laky and Ján Zavarský (the meeting which they initiated sometime in the early 1970s), the ten years older Filko acquires new and inspiring partners for debates that would evolve from scientific descriptions (Time I, Time II), utopian communications (Cosmic Messages I) to Malevich’s inspired search for transcendence through monochromatic painting.

More than the inclination towards piety, Wittgenstein’s notion of a ladder to be thrown away after we have climbed up it is more apt in this context (Tractatus, 6.54).

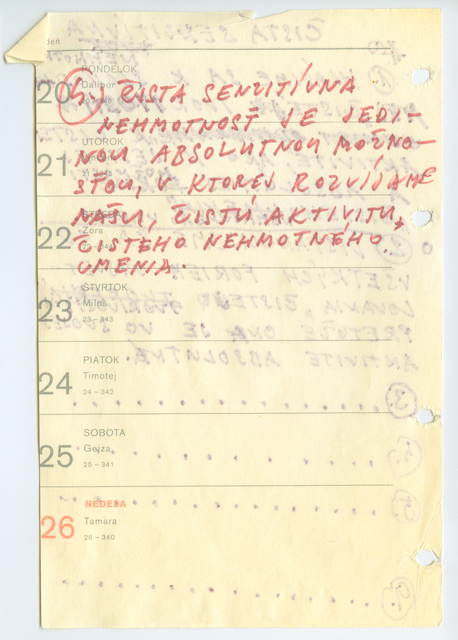

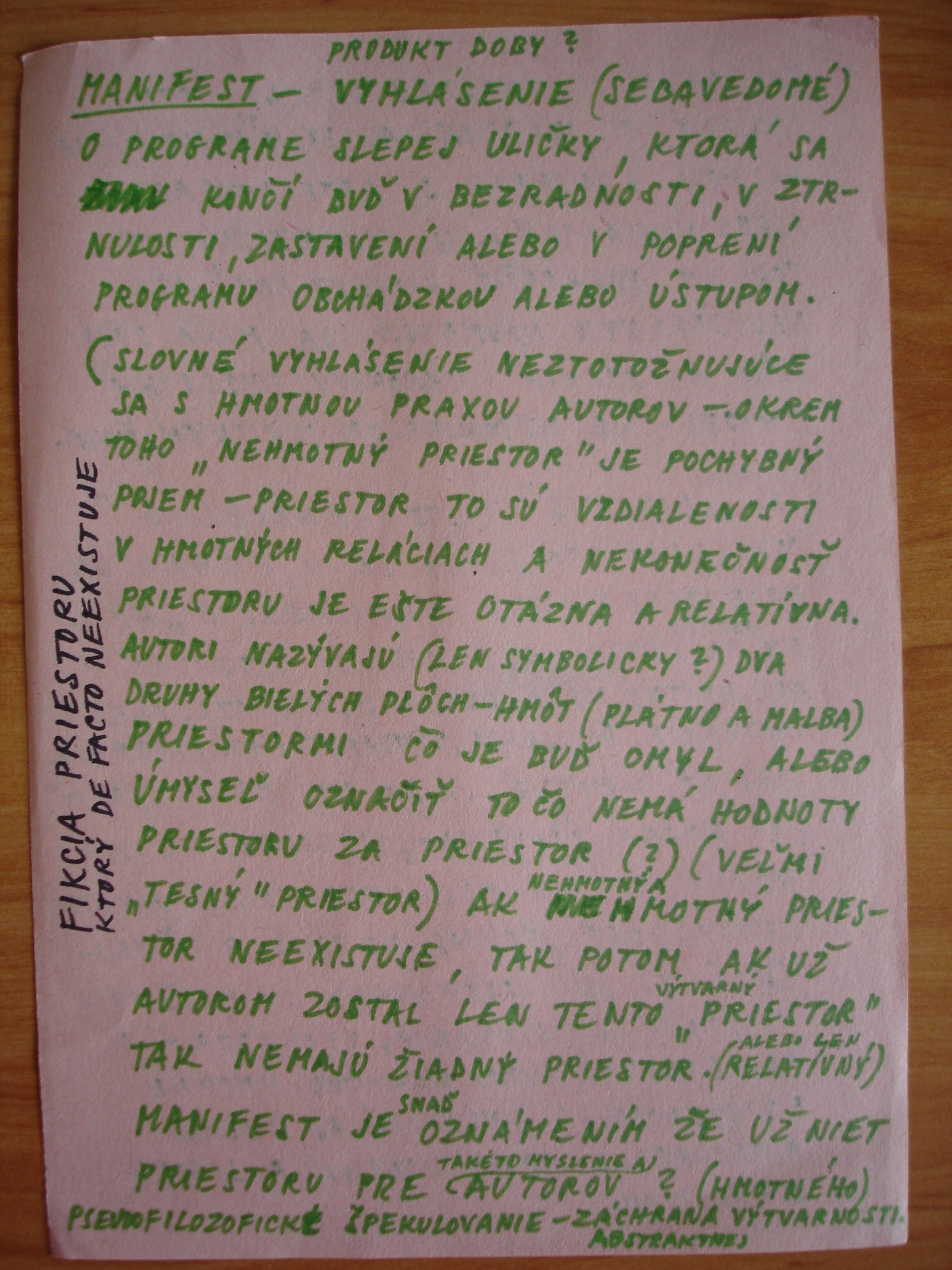

The White Space manifesto in Laky’s handwriting, 1974.

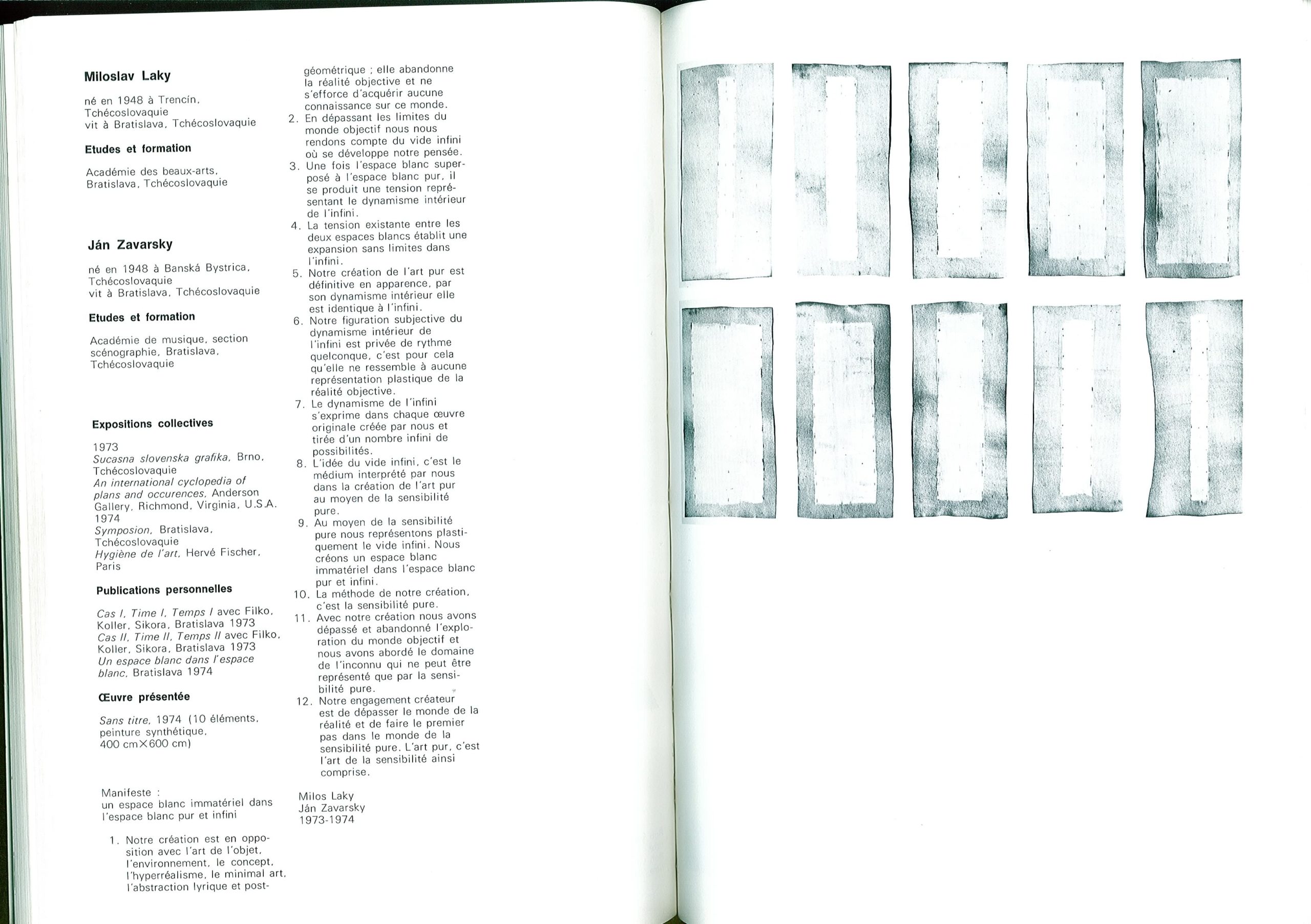

White Space in White Space

From the end of 1973, Filko, Laky and Zavarský developed one of the most radical art programmes of the Slovak neo avant-garde, White Space in White Space (1974-75). The key to the programme was a manifesto and its first point was to distance from all previous forms of art, as it was stuck in objectivity which had to be overcome through pure sensibility, mediated neither by matter nor by spirit (ideas).

The idea is that the immaterial is infinite, and infinite, like a mirror image in a mirror, is the space that is created by layering or pasting something into something (white on white).

As authors say, the White Space is art free from any objecthood, it is an art of pure sensibility, while its absolutising claims to comprehension are not an unattainable ideal, on the contrary, they are to be a concrete and natural part of the reality. In other words, pure sensibility can be experienced and shared together on the level of „pure emotions”; it is therefore real and comprehensible, yet cannot be explained. In this sense, it is precisely collective authorship – „the super-subject“ – that appears to be a necessary condition for corroborating some of the grand theses of the manifesto. At the same time, however, it continually raises questions about the personal participation and contribution of all the involved.

Filko used to comment on this generously, describing the making of the White Space as a rare super-personal consensus in art according to his own principle of “together every man for himself”. “When we made the White Space I wanted to present my work as a super-subject,” he later explained to Ján Budaj in a samizdat interview. Ján Zavarský also always stressed the “dialectical” nature of the process of creation, that the work was created in a collective discussion, but at the same time he refused to admit that the initial impulse and initiative came from Filko. Boris Ondreička made an interesting observation in this regard when, in his essay Filko’s Albedo, he wrote that “Laky was the heart, Zavarský the mind, and Filko the hand of the White Space”.

The whole thing began to resemble a search for some kind of worldly transcendence. At first glance, the move from the science-oriented Cosmic Messages to the metaphysics of the White Space might have seemed rather wild, and one cannot but think once again about the metaphor of throwing away a ladder after someone has climbed up it. Ján Zavarský explained it in an interview with Daniel Grúň that the need to turn attention to transcendence was a natural outcome of a certain disappointment with technology, which always has its limits.

Practically speaking, it was the application of white latex paint with a paint roller on tubes covered with canvas or directly on white canvas, later replaced by felt. This formed the core of the White Space which was produced in large volumes during the meetings in Filko‘s studio.

The symbol of the complete fusion of art and life later became the Laky’s new flat, which he and his girlfriend Anna Hurbanova transformed into a total flat installation, where all the furnishings were white and thus contributed to the materialisation of an experience of pure sensibility. Ľubomír Ďurček remembers the strange, illusory atmosphere of this physically existing white space, which had a decomposing effect on senses, causing a “sensory” shock to the visitors after leaving the flat back to reality.

White flat of Miloš Laky and Anna Hurbanová.

The flat hosted the meetings of artists – even Július Koller did not refuse the invitation – as well as performances of invited guests, for example, the Prague philosopher Petr Rezek lectured there on action art in 1976.

A meeting in Miloš Laky’s flat. From left to right: Filko, Ďurček, Štraus.

Koller’s Critique of White Space

The radical nature of the White Space did not arouse suspicion only on public, since the work was completely unacceptable from the point of view of the official aesthetics of the time. It was only possible to document it thanks to a secret, half-day installation held on 18th February 1974 in the House of Arts in Brno, which was a Monday and therefore a day when the gallery was closed.

The White Space installation, 18th February 1974 in the House of Arts in Brno.

He also sowed distrust within the group of unofficial artists. An undated 9-page manuscript was found in the estate of Július Koller; in it the author refutes the individual points of the manifesto in a concentrated and detailed manner. In it, he harshly condemns the White Space, considering it “a dead end that ends in either cluelessness, rigidity, halting or denying the programme by detour or retreat.” According to Koller, this is “pseudo-philosophical speculation – a salvation of abstract art.”

Július Koller’s handwritten critique.

The Koller’s critical commentary is obviously personally motivated, since – as Aurel Hrabušický noticed – “this is just strange of a man who was the author of cosmological culture, who contacted Atlantis and extraterrestrial civilisations through his UFO outward appearance, but who approached this text, the White Space Manifesto, with a kind of a common sense.” Vladimir Havrilla was similarly critical of the White Space in his own peculiar way, tersely ironising individual points of the manifesto.

Ján Zavarský recalled the circumstances of the creation of the White Space and the immediate reactions to it in 2010 in a discussion with his colleagues as follows: “We met and talked. In various places. And in that situation and in that place, we produced this thing and we were met with enormous criticism. You almost ate us up. I remember that. First of all, the hanging picture is long gone, what else is there to paint, plus the philosophical nonsense cackling. Jožo Jankovič was so mad he jumped two meters into the air. I’m not slandering him, I’m just saying that it was widely perceived as a provocation. Julo Koller wrote 9 pages; he must have written like a Czech gendarme. It provoked our union officials, and in retrospect the ŠtB, who were furious and shouted that we should paint socially engaged art. When they interrogated me, they couldn’t figure out what the white was about. If it was at least red, they said.”

White Space and State Security: Filko with Dalí on Corrida

Just like in the case of Tomáš Štraus, or later Juraj Mihálik along with Alex Mlynárčik and other similar leaders in the environment of artistic communities, it was so in the case of Stano Filko: the real circumstances of his life against the background of his artistic and spiritual development in the early 1970s are marked by politics, but especially by the State Security and their interest in his person.

“Filko appears to be a very strongminded and temperamental type, with a distinctive approach to a wide range of daily problems. His peculiarity manifests itself not only in his work, in which he does not conform to any fashionable line, even if it were more convenient for him, but also in his social intercourse, where he finds it more difficult to submit to the will of others. In this regard, a thorough knowledge of him is important, since his manner of speech and behaviour have a touch of arbitrariness which disappears only on closer acquaintance and knowledge of him. His personal predilection is predominantly an interest in all schools of art and in visiting galleries.” – Memorandum of a candidate for secret collaboration with the code name “Akademik” (ŠtB, 11th January 1973)

Today it is impossible to determine which of the unfinished artistic concepts Filko carried in his head at the beginning of March 1973 when he went to a meeting at the Europa café in Pezinok town where in the company of his commanding officer, Captain Partl, and the head of the 2nd department of the XIIth administration of the ŠtB, Major Obuch, he signs the so-called binding act. The State Security establish a file of the agent with the code name “Akademik”. Filko chose the password for any unplanned meetings with the ŠtB operative with humour:

“Have you met Salvador Dalí in Spain?”

“Yes, we were together at Corrida.”

As a collaborator, he was to be used to “persons of pro-French leanings: Žilinčanová Viera, Jakabčic Michal, Mlynárčik Alexander, Kára Ľubomír. Furthermore, to the former artists in exile in France and West Germany: Čulík Peter, Kováč Rudolf, Tausig Pavol, Tehnik Karol, Liskovský Karol, deemed interesting by the ŠtB.”

What we can read from the fragment of his personal file preserved in the archives of the Nation Memory Institute is his psychological profile, the course of his recruitment, as well as his plans and expectations, which, however, did not come true at all. That is why after two years, in March 1975, the ŠtB placed his file into archive due to the “agent’s unseriousness”. The explanatory report to the file archiving, dated 24 March 1975, states:

“Filko was continually tactically pushed on the above actions and other interesting contacts in meetings, but never once commented on the said contacts or even hinted that he maintained such contacts.” Moreover, according to reports to the ŠtB from the painter Karol Lacko, Filko was then “known among the members of the Union of Visual Artists as a security agent, which clearly testifies to his deconspiration.”

In the given period, Filko succeeded to repeatedly travel to the West despite existential hardship and political persecution. It is therefore likely that contacts with the ŠtB were part of his effort to maintain his passport and travel opportunities. This is also indicated by a remark in the recording of his recruitment saying that “Filko thanked for help with arranging the documents for the trip to West Germany, France and Switzerland” that he was planning at the time.

Meanwhile in Bratislava, Filko together with Laky and Zavarský form a super-individual artistic subject which declares the denial of all forms of contemporary aesthetics, but mainly the total negation of the prevailing Marxist-Leninist materialist philosophy.

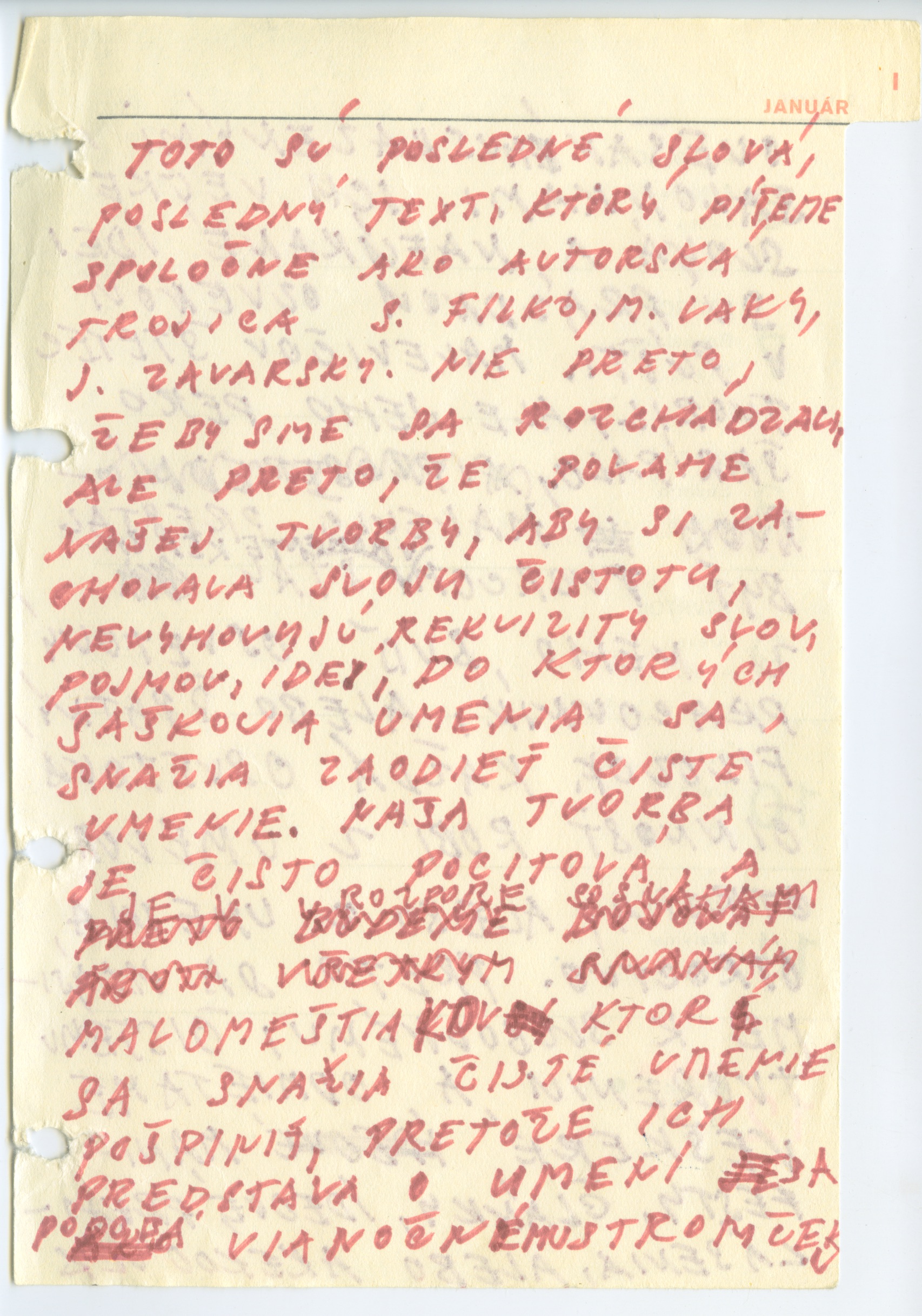

Laky dies, White Space Comes to Life in Paris

Miloš Laky graduates from university in May 1974. Shortly after his health deteriorates and he finds out that he suffers from a form of cancer that is difficult to treat and has a rapid progression. For the last year of his life, Laky continues to develop the existential ideas of pure sensibility. At this point, Filko takes advantage of his opportunities to travel and, in the summer of 1975, he takes the gravely ill Laky on a dream car trip around European galleries in Vienna, Paris and Amsterdam.

Three days before his death (4th September 1975), Miloš Laky finishes the second manifesto of the White Space in White Space, in which he further radicalises his positions on the matter of pure sensibility of pure art, contesting philosophy in art, and proclaiming the incompatibility of ideological ballast with the activity of pure sensibility. Perhaps deliberately, and perhaps subconsciously, he thus refers to the solipsism of George Berkeley, who, in his Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, also contemplates the emergence of emotions “without any mediation by ideas”.

Laky’s handwritten manifesto of the White Space, 1975.

Two weeks after his death (19th September 1975), the Youth Biennale opens in Paris, where the artistic duo Laky and Zavarský exhibits among the hundred shooting stars of the contemporary world art. In order to exhibit the White Space in Paris, Filko renounces the association of his name with the project, as he was the only one of the trio who did not meet the age limit of 35.

The catalogue of The Youth Biennale, Paris, 1975.

The competition is fierce, yet the installation, consisting of ten painted felts and a manifesto translated into several world languages, attracts interest. Ján Zavarský is offered to exhibit at the prestigious Parisian gallery Eric Fabre and, in his words, it was only his participation in Paris that “broke the reluctance” to the White Space at home. “By exhibiting in Paris, even Tomáš Štraus changed his mind,” he recalled in 2016.

Young Slovak artist Miloš Laky did not live to see the later recognition of the concept of the White Space in White Space.

Miloš Laky’s white tombstone at the cemetery in Mlynská dolina, Bratislava.

The collective programme comes to an end after Laky’s death. Filko and Zavarský start families and go their separate ways. Zavarský’s footsteps lead to theatre and stage design, where he also gives a remarkable performance, and Filko goes back to the concept, where, in his own words, “he keeps tweaking the problem of the White Space” and will not stop doing so for the rest of his life.

Sometime in the second half of the 1970s, at a personal meeting with Ján Zavarský, Filko makes Zavarský agree that he takes over and continue the programme under his own name. He writes further manifestos (Emotion,Transcendence, Transcendental Meditation), paints white stripes on the ceilings of galleries in Poland and Yugoslavia, and finally, disgusted with his own position and the situation in Czechoslovakia, emigrates to West Germany. Shortly after, in 1982, he exhibits his white Škoda 105 car painted white at the Documenta in Kassel.

Stano Filko’s installation, Documenta 7, Kassel, 1982.

Post Scriptum 1981

Probably in order to keep his passport and to be able to travel abroad, Filko continued to maintain forced contacts with the ŠtB members even after 1975, at that time in the category “confidant” in form of unconscious cooperation.

In February 1981, in this way (unknowingly), he left a piece of information in the ŠtB files about his friends and acquaintances, when at a meeting he mentioned that Vladimír Havrilla, Ján Budaj, Rudo Sikora and Ľubomír Ďurček were collecting catalogues for their mutual friend Pavel Büchler from Prague, who was at that time about to travel to the West. As a result, the ŠtB ordered to conduct interrogations with Sikora, Havrilla and Ďurček.

This could also be the price of the need to emigrate under normalisation and “to still yearn for great things” in the free world, as Filko formulated his credo in a 1983 letter from New York to his friends in Bratislava.