Essay / PROJECT OF RECOGNITION

The group VAL / Voies et Aspectes du Lendemain / Viera Mecková, Alex Mlynárčik, Ľudovít Kupkovič produced 8 projects during the years 1968(72) – 1994. Looking at the individual projects, their theoretical and practical backgrounds, the position of the group within the local and global context seems ambivalent. They move from place to place.

In the introductory text of the catalogue accompanying their first solo exhibition in Slovakia [1], architect Antonín Stuchl said of VAL that “although one can sense a certain ideological affinity with French New Realism and thus between Mlynárčik and Restany, and later also with Ragon, their work does not seek the favour of any particular group, does not follow any models, nor does it propose any revolution against any academicism. It is only their own work, combining technique and poetry with the values of the whole big world.”[2]

VAL is characterised by its affinity with the concept of prospective architecture[3]. From the point of view of domestic art history, VAL’s activity is classified with the neo-conceptual scene[4], the architectural variant of conceptual art[5], neo-constructivism[6], dematerialised art[7],… In terms of architecture, it is put in the context of the monumentalism of late modernism[8]. The work of the VAL group is described as scientific, philosophical, poetic. An intellectual escape “elsewhere”. It is a syncretic event at the boundary between architecture and art, when, in their total relationship amplified by each other, one expressed itself more freely in the language of the other, on the basis of reciprocal escapes.

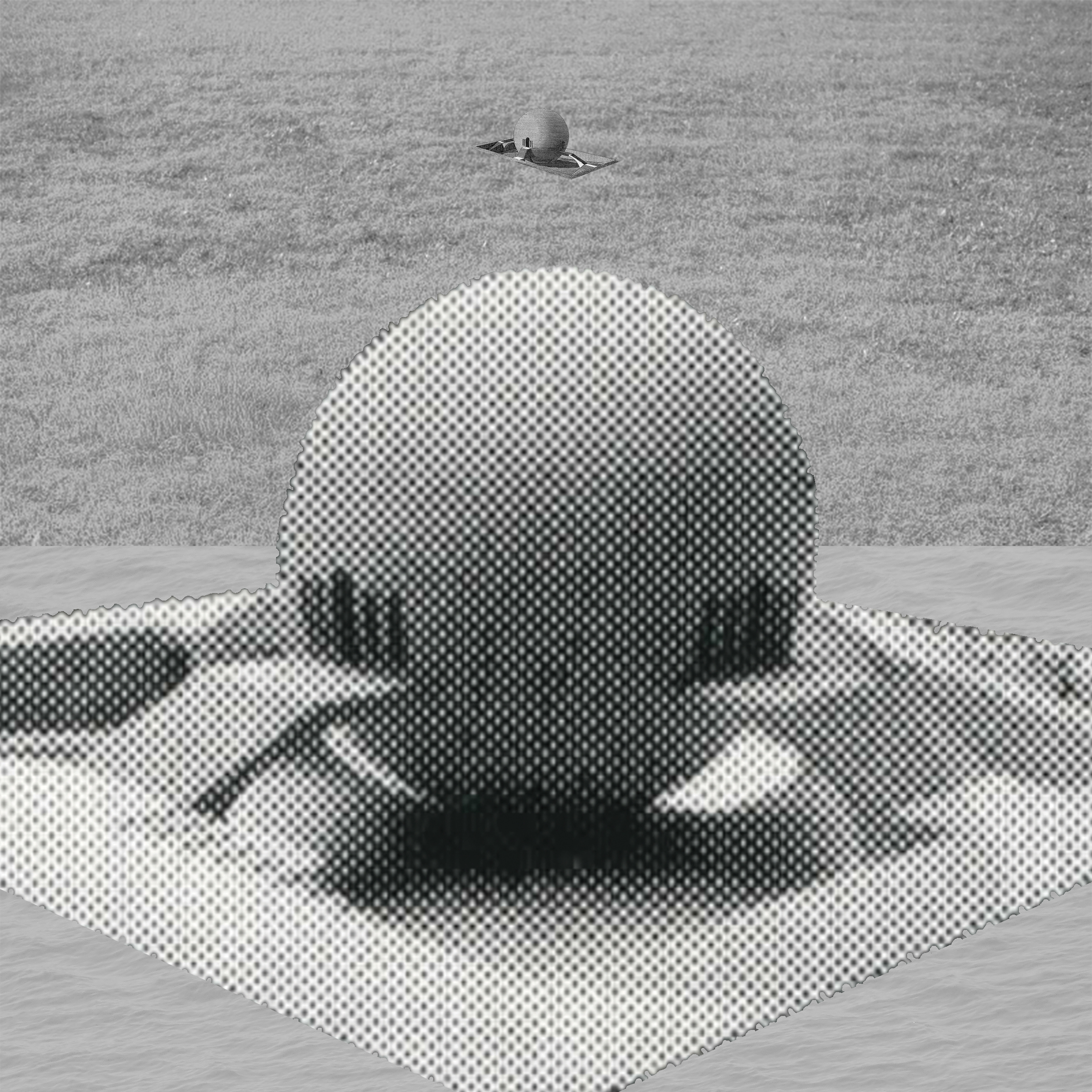

People’s Assembly of Argillia, VAL, 1980 – 1994, photo: Ľudovít Kupkovič.

I.

VAL’s projects are a tribute. Some explicitly, but I think they are all some form of tribute, to something or someone who was worthy of it. I’ve been thinking about how homage can materialize in a project, how homage manifests as a mode of making (architecture).

“No one will convince me that Einstein didn’t know how to divide and multiply. No one will convince me that Cézanne, Seurat, the cubists, the surrealists, etc., etc. discovered something out of nothing. The great ones struggled and toiled immensely hard to find that tiny speck – otherwise the keystone of their existence – the creative moment that meant Addition. This Adding to the past, but revealed by the scent and breath of the present. The Addition is the bridge that then allows for the continuation of the future. That is how it has always been.” (Alex Mlynárčik, from correspondence with Tomas Štrauss)[9]

II.

Argillia, the “ready-made state”, is a larger project of Alex Mlynárčik, which he began to develop around 1972 with his friends and acquaintances from all over the world (who became its citizens and dignitaries). Argillia, the “kingdom from elsewhere”, whose king was Mlynárčik’s friend “Ondrej Krištofík called the Smoker”, is first and foremost “a tribute to the common man”. As Mlynárčik further explains, the name of this state comes from the Latin word argilla,argillae – potter’s clay, and thus Argillia is a kingdom of clay.10 “A land without borders! A land without power! A land of human dreams, of desires. Love. A land of friends. A land of cheerful being.”[11] Argillia is a game “whose rules were the flip side of power’s reality.” Over time, it has acquired many institutions around the world, and among them the People’s Assembly.

One of VAL’s most recent projects is the People’s Assembly of Argillia (1980-1994), a global parliament located on the islands of Bora Bora in French Polynesia, in a setting “that is at once beautiful and symbolic: a protective wall of coral lagoon holding back the stormy waters on the surface of an endless ocean. The unique natural setting is ideal for meetings, for meditation, for reconciliation.”[12] People’s Assembly building is at the same time a tribute to the French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806) and conceptually rooted in his design for the Maison des gardes agricoles [House of the Agricultural Guards].

Maison des gardes agricoles, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux / People’s Assembly of Argillia, VAL, 1980 – 1994.

III.

National Assembly building is a tribute to one of the architects whom Emil Kaufmann regenerated in the mid-twentieth century and called revolutionary[13]. These architects (Ledoux, Boullée, Lequeu), according to Kaufmann, sought to renew the discipline, to innovate. At the same time, the search for the origins of the architecture of this period correlated with the search for the foundation of a newly forming (civil) society. In that these architects were active during the last years of the monarchy, and some continued after the French Revolution, their work, according to Kaufmann, reflects the restlessness of the times.

“The similarity between many of Ledoux’s works and those of the present leaves no doubt that he anticipated the future…Ledoux was among the first to visualize a new formal ideal.”[14] In his designs, he gradually moved away from traditional (Baroque) principles; through elementary geometric shapes, he sought new and more equivalent ways of arranging the elements, of composing buildings.

Kaufmann considers the House of the Agricultural Guards to be one of his most daring projects. House of the Agricultural Guards is part of a design for a chateau on the Mauperthuis estate that was commissioned from Ledoux by the Marquis of Montesquiou-Fezensac, but was never realised. The house is a perfect sphere housed in a sunken “bathtub”, accessed by four bridge-staircases on each of the cardinal points. Ledoux pursues the symbolic meaning of architectural forms. The sphere is, in his view, “magnificent and significant like the pyramids”.

Ledoux was also reflected in our domestic context. Jiří Hrůza devoted a short chapter to him in his anthology of utopian concepts[15], as a representative of architects who “have been of interest especially recently in the search for the sources and roots of modern architecture”[16].

Maison des gardes agricoles, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux / People’s Assembly of Argillia, VAL, 1980 – 1994.

Maison des gardes agricoles, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux / People’s Assembly of Argillia, VAL, 1980 – 1994.

IV.

People’s Assembly of Argillia is a tribute to Ledoux, an interpretation of the House of the Agricultural Guards. I will try to break down what has happened from one to the other and formulate what Ledoux might have been honoured with. What is different, first of all, are the environments in which the objects are placed. House of the Agricultural Guards is embedded in a farmland, sheep graze around and the sun shines – does it part the clouds? People’s Assembly building is embedded in the lagoon of the islands of Bora Bora, partly embedded in the mainland and its volcanic mountains.

For eighteenth-century (revolutionary) architecture, the relationship with nature was important. It was the period of Rousseau’s return to nature, Laugier’s primitive cottage. Architecture wanted to be in symbiosis with nature, to be a metaphor for it. House of the Agricultural Guards can refer to the sun, which, together with the clouds, forms an essential part of the depiction. Perhaps their relationship is important – the weather, as an important factor in agricultural success. National assembly is elsewhere. It may be in the middle of the South Pacific, but it is in an island lagoon that evokes a sense of calm in the midst of a wild ocean. In a place as removed and isolated as possible from the hotbeds of civilization, at the same time in a luxury holiday resort,in an idyllic natural landscape. People’s Assembly is a relocation of the House of the Agricultural Guards into a new context, the architecture loses its direct metaphorical relationship with the landscape as it did with Ledoux.

At first glance, the building of the People’s Assembly of Argillia appears identical to the House of the Agricultural Guards. Both buildings consist of a main volume (the sphere) and a base (the tub) in which they are somehow contained. Four bridge-staircases with entrances facing the four cardinal points are present in both versions. Ledoux has placed his sphere relatively stably on the ground, it is nested in its base (the tub), VAL’s sphere floats in its base.

The rectangular tub of the House of the Agricultural Guards, which is submerged in the ground, turns into a hemispherical bowl submerged in water at the People’s Assembly. The sphere that has been fixed, tethered to the ground, in the case of the People’s Assembly, detaches, floats. Its freedom is not absolute; its four bridges-staircases connect it firmly to the base and, eventually, to the land. It seems that the looser the sphere is, the more of a sphere-idea it is. “Ultimately, the sphere is a deeply atectonic form – baseless, separated by its perfect regularity from the forces of gravity, it is actually a metaphor for weightlessness, for separation from the Earth.”[17]

Ledoux’s pupil, Jean Nicolas Sobre, metaphorically hinted at such liberation in his version of the floating sphere, Temple à l’Immortalité [Temple of Immortality], in which, according to Hrůza, he brings the principle of the spherical structure to perfection. It is “a monumental meeting hall inside a precise sphere, whose perfection he apparently does not want to disturb even by any support, and therefore he draws it as floating on a lake.”[18] While Hrůza apparently thought it was a whole sphere, it is in fact a floating hemisphere about eighty meters in diameter, also with openings on the four cardinal points. The temple was to be placed on the lake on the Champs Elysées[19] so that its reflection in the water, when viewed from a distance, would give the appearance of a perfect whole sphere. Temple of Immortality is not just architecture that wants to be a metaphor for nature, but it is complete in the union of nature and architecture, it is made by nature.

The ideal of the new (prospective) architecture to which VAL subscribes was the detachment from the earth, which is related to the prognosis of gradual overpopulation, the overconcentration of people in cities, but also the degradation of the environment due to accelerating industrialization,…in a way, the impossibility of being tied to it. While Sobre achieves liberation (the ideal of the sphere) through illusion, VAL demonstrates it through technical means and design possibilities. The image that Sobre evokes through a metaphorical relationship with nature – the project of prospective architecture addresses rationality.

When I look at the sheep in one picture and the volcanic mountains in the other, I realize that the scale of the objects can’t be the same. The House of the Agricultural Guards is about 20 meters (10 toises[20]) in diameter, while the sphere of the People’s Assembly is 230 meters (230 feet). VAL Ledoux’s object inflated almost tenfold. By comparison, Boullée’s notorious Cénotaphe de Newton is approximately 150 metres in diameter.

The element that breaks the abstractness of the whole object and could suggest the scale of the House of the Agricultural Guards is the door.21 In VAL’s project, the same element becomes very ambiguous. Proportionally, it remains the same and, unless one is aware of the overall increase in volume, it gives the impression of the identity of the two objects. To determine the size of the object is unpronounceable. It is a monumental entrance portal, transformed into an entrance space that is approximately 18 metres wide and 40 metres high.

VAL has monumentalized the Ledoux House, both in the sense of absolute size – enlarging it – and in meaning – changing the use of the building as an important world institution. Is this a form of literal homage – monumentalization – an inflation of Ledoux? Moreover, the sphere seems an ideal form for demonstrating both importance and equality. The sphere is not about height or vastness, it is about size – volume in its purest form. There is no direction in it, it has no direction. It is not rooted in anything, it has no above or below, it is without hierarchy. This legitimizes it as a symbol of the world parliament.

V.

Eighteenth-century architectural theory used (among others) the term caractère, the meaning of which was defined differently by different architects, but it was roughly an expression of the function of the house. Not in a utilitarian or structural sense, but in the sense of a symbol that evokes associations and educates.22 The house showed its inhabitant, its content. A special case of this thinking was the architectural parlante, which is mainly associated with revolutionary architects. A building explains its function or identity through its formal attributes.

The interiors of the House of the Agricultural Guards and the People’s Assembly building are already completely different situations. The House of the Agricultural Guards has a three-storey, classical nine-square layout: on the ground floor there are greenhouses and stables, on the main floor there are four bedrooms and a common central kitchen, and on the top floor there are storage rooms. Ledoux inserts an orthogonal grid of walls into the spherical envelope, giving a relatively practical layout as opposed to an ideal volume. Habitability is sacrificed to the symbolic value of geometric form.

VAL has completely changed the inside of his sphere. It takes the predisposition of the form (the sphere) itself and uses it as a panoramic tribune – a forum and lodge of the envoys of the nations of the upper and lower houses. The double shell contains administrative and technical spaces, while the hemispherical tub contains hotels, social spaces, places for culture and sport, as well as technical and transport infrastructure. The sphere is filled with functionally more logical, and meaningfully more adequate content.

The internal structure of the House of the Agricultural Guards is in contrasting relationship with its envelope, and the practical content with the expression of the house as a whole. Ledoux, especially in his later works, moved away from the traditional concept of unity towards decomposition. “In his search for new spatial solutions, Ledoux became a true forerunner of the twentieth century,” Kaufmann[23] argues. His buildings appear as interpenetrating masses, or as assemblages of discordant, contrasting, disproportionate elements. In the case of the House of the Agricultural Guards, it is a kind of dissociation of interior (content) and exterior (shell). The House of the Agricultural Guards, a habitable house, is neither monumental in its dimensions nor in its practical content. With what I have already mentioned about the sphere, it is questionable whether the chosen form and its symbolic meaning are not trivialized by its use. In the case of the National Assembly, this is no longer in question. The monumental expression of the geometric form, supported by the inflation of the dimensions, seems to be more appropriate to the building’s new purpose.

People’s Assembly is an act of emptying, and refilling. It shows the House of the Agricultural Guards as a form significant in itself. People’s Assembly project takes the house as its base, which is an example of questioning tradition (or just the established way of maintaining it) and finding a new expression. This house, which already offers itself as an aggregate of parts, is further deconstructed, formalised and monumentalised, thus giving rise to a form. Through this process, emptying and filling, the form of the House of the Agricultural Guards becomes the bearer of continuity. A way of schizophrenic transmission of tradition. A monument that may take on meanings, change meanings over time, but it is still a monument – a living one.

I don’t know what is the real reason for the VAL’s tribute to this architect. I have described part of what I have seen. Ledoux, his projects also represent other things. It could be the context of the period of the formation of civil society, the materialization of new ideals in the design of civic buildings, a more philosophical and conceptual view of architecture,… Maybe a tribute to the abandonment of routine.

Maison des gardes agricoles, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux / People’s Assembly of Argillia, VAL, 1980 – 1994.

1 The exhibition VAL – Cesty a aspekty zajtrajška [Paths and Aspects of Tomorrow] was held in 1996 at the Umelecká beseda in Bratislava, then in 1997 at the Klasik Gallery in Žilina. It was also their first exhibition where all 8 projects were presented.

2 KUPKOVIČ, Ľudovít – MECKOVÁ, Viera – MLYNÁRČIK, Alex. VAL Cesty a aspekty zajtrajška (exhibition catalogue). Žilina: Expresprint, 1995, 159 p.

3 The theory of prospective architecture is defined by Michel Ragon in the publication – RAGON, Michel. Où vivrons-nous demain?. Paris: Édition Robert Laffont, 1963. A Czech translation was subsequently published in Czechoslovakia – RAGON, Michel. Kde budeme žít zítra?. Prague: Mladá fronta, 1967. Later, in 1965, the manifesto of the GIAP (Groupe International d’architecture prospective), of which Michel Ragon was an initiator, was published. Later, at the end of the seventies, he published a publication – an “encyclopaedia” of prospective architecture – in which the project of the VAL group already appears. – RAGON, M. Histoire mondiale de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme moderne. Prospective et futurologie. Paris: Casterman, 1978.

4 BARTOŠOVÁ, Zuzana. Napriek totalite. Neoficiálna slovenská výtvarná scéna sedemdesiatych a osemdesiatych rokov 20. Storočia. Bratislava: Kalligram, 2011.

5 ŠTRAUSS, Tomáš. Slovenský variant moderny. Bratislava: Pallas, vydavateľstvo SFVU, 1992, 197 p.

6 KURACINOVÁ-JANČEKOVÁ, Viera. Neokonštruktivizmus v slovenskom výtvarnom umení (exhibition catalogue). Trnava: Galéria Jána Koniarka, 2000.

7 Hrabušický uses this term in his text Umenie fantastického odhmotnenia [The Art of Fantastic Unmasking] in the catalogue to the exhibition Slovenské vizuálne umenie 1970-1985 [Slovak Visual Art 1970-1985], organised by the Slovak National Gallery at the turn of 2002 and 2003 in the Esterházy Palace. It brings closer the specific character of conceptual art in Slovakia.

8 DULLA, Matúš – MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta. Architektúra Slovenska v 20. storočí. Bratislava: Slovart, 2002.

9 From personal correspondence with Tomáš Štrauss. Letter written in Bratislava, 14 July 1979. The correspondence was published In: ŠTRAUSS, Tomáš. Slovenský variant moderny. Bratislava: Pallas, vydavateľstvo SFVU, 1992, p. 197.

10 MLYNÁRČIK, Alex. P.S.: Zápisky z cesty A.M. Self-published, 2011, p. 197.

11 MLYNÁRČIK, Alex. P.S.: Zápisky z cesty A.M. Self-published, 2011, p. 197.

12 KUPKOVIČ, Ľudovít – MECKOVÁ, Viera – MLYNÁRČIK, Alex. VAL Cesty a aspekty zajtrajška (exhibition catalogue). Žilina: Expresprint, 1995, p. 93.

13 KAUFMANN, Emil. Three revolutionary architects: Boullee, Ledoux, and Lequeu. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series – Volume 42, Part 3, p. 434. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1952.

14 KAUFMANN, Emil. Three revolutionary architects: Boullee, Ledoux, and Lequeu, p. 479.

15 HRŮZA, Jiří. Města utopistů. Praha: Československý spisovatel, 1967.

16 HRŮZA, Jiří. Města utopistů, p. 47.

17 VON FALKENHAUSEN, Susanne. The Sphere: Reading a gender metaphor in the architecture of modern culty of identity. In: Art History: journal of the Association of Art Historians, vol. 20, no. 2, 1997, pp. 238-267.

18 HRŮZA, Jiří. Města utopistů, p. 68. “His pupil, Jean Nicolas Sobre, takes this principle to the extreme in the design of the “Temple of Immortality” as a monumental meeting hall inside a precise sphere, whose perfection he apparently does not want to disturb even by any support, and therefore draws it as floating on a lake.”

19 COLLINS, George R. The Visionary Tradition in Architecture. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 26, no. 8, 1968, pp. 310–321. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/3258445 (Accessed: 20 July 2021).

20Toise was a length measure in France before the French Revolution, 1 toise equals approximately 1.96 metres.

21 Palladian (Venetian) doors, a motif that Ledoux varies in almost all his projects. “The transformation of the Palladian motif, too, have deep significance. Originally this motif meant the supremacy of the central portion, and the integration of all its parts; it was a true symbol of baroque order. Ledoux again and again deprived the motif of this meaning by various modifications.” KAUFMANN, Emil. Three revolutionary architects: Boullee, Ledoux, and Lequeu. p. 530.

22 KRUFT, Hanno-Walter. Dejiny teórie architektúry. Od antiky po súčasnosť. Bratislava: Pallas, 1993, p. 176.

23 KAUFMANN, Emil. Three revolutionary architects: Boullee, Ledoux, and Lequeu, s. 488. “In his search for new spatial solutions, Ledoux became the true precursor of the twentieth century. In ever varying attempts he wanted to present buildings: as aggregates of interpenetrating masses; or as piles of stepped off units (motif of contrasted sizes); or as assemblage of incongruous elements (motif of contrasted shapes).”

The essay originally appeared in magazine Jazdec: Revue súčasného výtvarného umenia, in 2021, issue 41.