Interview / DESIGNER PETER LEHOCKÝ

Boris Ondreička: How does a boy from a small village – Drietoma – become a designer?

Peter Lehocký: I’ve been drawing something since I was very little. It was something like a gift from God. My dad gave me “Manes” paints – a set of oil paints, turpentine and flax seed oil for my 15th birthday. That evening I painted something on a shoe box. The shoe box was made of very good cardboard. Naturally, it was just a child’s act, not art. But perhaps it was a moment that moved me more particularly forward towards further decision making about my own future. When we were children, me and other kids from Drietoma made different puppet shows. We sewed puppets. I created and lit the stage by putting colourful filters on torches. Then we played shows for neighbours and cousins.

BO: Was your father technically or artistically oriented?

PL: No, my father was an outstanding civil servant, a true notary. He had neither a technical, or artistic leaning, but he had marvellous handwriting. Our family tree he put together is pure beauty. I still have it. Maybe by watching me, he wanted to help me get to know myself and become something I wanted to be.

BO: So where did this knowledge to wire a bulb and such come from?

PL: Dunno, spontaneously. All the components could be bought in model shops – all the railway models and so on. Then I decided to continue at the vocational high school in town of Nové Mesto nad Váhom. It was a pain at the beginning, actually until I was in the second to last year when we took up the subjects of precision engineering and optics. That’s where we started touching glass and lenses. We learned to distinguish different types of glass: lead, simax ones. Simax glass is hard, laboratory-made glass with a huge resistance. I haven’t lost my interest in them ever since.

BO: So if there wasn’t an Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, which craft would you do?

PL: Right after leaving school I started working as a constructor in the Trenčín’s research and development company Konštrukta. Our more or less universal studio that included chemists and so was called Development office 5. We were working on the innovation of calendering cylinders designed for large-scale textile ironing. We worked also on rolling mills for Košice. I spent five years there, including my military service. I served mainly as an athlete in Dukla (military sport centre) where I also started doing some graphic design: large posters, invitations, mostly using linocut. When I came back to Konštrukta I knew I wouldn’t stay there for long, because I wanted to move on. My mum was crying; I had a rather decent income and I became independent. My first steps led me to the Zlín’s studio of industrial designer and sculptor Zdeněk Kovář – as an author of the Tatra 603 truck and other things, he was a legend already back then. Kovář led the Studio of Machine and Tool Shaping detached from the Academy of Arts, Architecture & Design in Prague. They informed me in Zlín that the Bratislava’s Academy of Arts and Design had recently opened a section of industrial product shaping under the lead of Brno’s professor Václav Kautman. When Kautman found out that I’d been technically trained, I had worked as a constructor before and I also had had craft skills, he immediately open the door for me, as he was in need of such a student and actually a technical assistant of sorts. Most of my later course-mates were from the School of Applied Arts. So I could consult him before I was duly accepted. We were the third year of design in the history of the academy. Kautman was great. He was responsible for introducing the order and systematics into production of high-level folk art. He also made the first logo of ÚĽUV (the Centre for Folk Art Production). Another positive feature was that as a sculptor he initiated the application of artistic thought to design. He let us do our work as freely as it got. Our section was in healthy competition with the Section of Glass in Architecture led by Václav Cigler. Kautman was a Moravian, Cigler a Czech. Our sections gave pain to the classical, relief, figurative sculptors (you know, the ones around Kulich etc.), they envied us, as what was allowed in sculptural expression (free-thinking) at ours, was unimaginable at their sections.

BO: This has always been very interesting to me and I am glad we can smoothly get to do it through your particular biographical data. That design, in a way an ideologically forgotten field, provided free space for very assertive abstract geometry in the times of “totality” as well. Yes, you can’t imagine it today, but just like we could only juggle with, say, a colour in sculpture, it was unimaginably free elsewhere.

But how did you get to the glass and light that dominate your production? After all, Kautman’s domain was mostly wood and narrative work, so to speak…

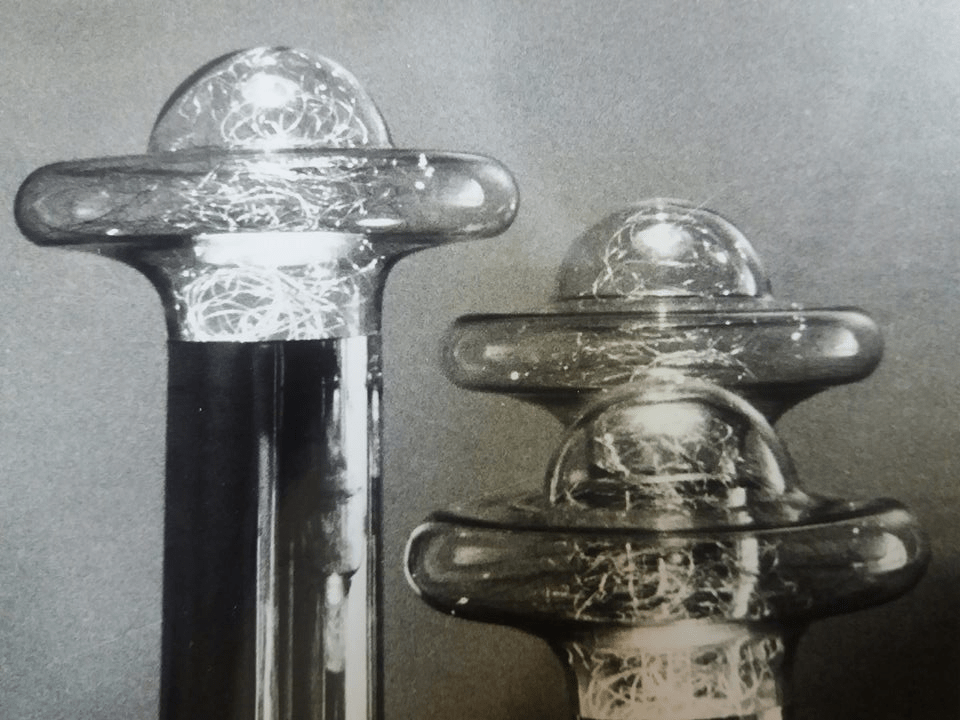

PL: Right after I’d graduated, I got my very first order from my architect friends – to make the fountain for the dormitories in Stará Turá. I needed to light it. So this is how glass came in. It was a fatal experience that hasn’t left me ever since. The fountain no longer exists, because fountains need a totally different care than for sculptures. The maintenance is the alpha and omega in thinking and drafting concepts of architectural and urbanist wholes. Then my path led me to the glassworks in Lednické Rovne. But I wasn’t successful, because I wanted to create objects overcoming their past and present capacities (when it comes to size, shape and materials). Therefore, already back then it was clear to me that it had to be simax. Simax, that is Si (silicium) and Max – its maximum content in glass. This glass is fantastic, because it can bear extreme heat shock. It’s boiling glassware, extremely resistant, “stubborn”, more suitable for exteriors. The best glass factories working with simax were in the Czech Sázava River region. I went to seven glassworks as far as Sázava, right to the biggest Kavalier factory. And once again, in vain; (in their opinion) I exceeded them dimensionally, but perhaps they only didn’t want the risk. So they sent me behind the “hill” to their branch, to some little manufacture – the glassworks in Růženín colony. This colony was established because of the factory and it had been named after the glassworks, not the other way around. Today (after the privatisation of Kavalier) it serves only as a warehouse. It’s sad. Their director at that time had close relationships with the plant in Dubnica nad Váhom and so not only did he agree to collaborate with me, but when he saw what I was after, he also arranged that I should make the ceiling lights for the administration of the Heavy machinery plant. I did all the prototypes and implementation solutions (30 one-litre object components, i.e. 40 kilos each) as well as my more intimate pieces in there, if they had the capacity for it. The lighting for the Trója Palace complex, Mariánske Lázně as well as the Franciscan Garden in Prague were also developed there. We were using moulds made from cherry or pear tree wood and Pecol for bigger things (mixture of cement, sand, graphite, fire clay…).

BO: Substantial materials touching each other in your work are glass and metal, holography and metal and light, electricity. Glass or metal are frozen liquidity, still keeping their magmatic origin. Maybe that’s why they are in such harmony. Your morphology (bionic, organic/round) totally corresponds to it. And they both are industrial materials (both are bent, both are welded…) – i. e. in your work we see a mutual communication of physical, scientific, technical and cultural aspects along with a certain mystique of birth and eternal germination of the natural. Even though they are created from eventually hard, cold materials, they don’t lack softness and the previous glare. Even though they are inanimate, they don’t miss the eminent associative power of fertility, growth/progress.

PL: And there is one more moment of connection that is important for me – reflectiveness. I like to work with high polished stainless steel. It is very high-flown, with a link to mirror which is also glass. I also like matting, whether glass or metal, and then I combine high polished and matt surfaces. It all reflects (literally) the natural phenomena in the cultural environment, like some forever blooming flowers. Glass bending that is often a question of seconds, keeping precise temperature, corresponds with natural processes, either in flora or in volcanic birth of mineral themselves.

BO: How did it come about that you were commissioned to realise the Mariánske Lázně (spa town) lighting?

PL: Ha, ha, ha. A team of the Slovak Television culture section was coming back from Žilina and they found out they had an extra celluloid. The editor Táňa Sedláková convinced them to stop halfway in Trenčín at my solo exhibition (I had that big blown glassware there already) to make a trailer. The local gallery had an excellent avant-garde programme, given our context. The invitation together with other stuff was broadcast by the federal TV in the main news programme. Based on that, an investor from Mariánske Lázně together with the State Institute for Reconstruction of Historical Cities and Objects called right after two days that this is precisely the expression they would like to see for the revitalised colonnade. In three days we had a meeting in Prague. The Institute financed and supervised the whole development. Today it appears as an utter miracle.

BO: Unbelievable! I am wondering about it also because conceiving public space made to measure with a unique individual approach totally vanished in 1990s. Cities thus become globalist non-identities. Urbanism is extremely fabricated, industrialised. It is a developer, not a specialist urbanist landscape architect that takes a lead, price-making and “cash-back”. That’s, in terms of quality, a disastrous regression.

PL: Architects and urbanists used to have a free hand at that time, but they were bound not to make individual components by themselves; those had to be done together with designers, glass makers, artists and other experts. Prague did not look at different public segments one by one, separately; the authorities drew up a concept of the whole of its panorama, taking into consideration all the disciplines. One of the leading personalities there was the phenomenal architect, designer, urbanist, landscapist and ČVUT (Czech Academy of Technology) teacher Otakar Kuča, a planner of the aforementioned State Institute for Reconstruction of Historical Cities and Objects (SÚPRMO). SÚPRMO was also an expert authority for all the Czech regions. So their task was not only to supervise, but also to present visions and strategies of future activities. They were the heads of those delicate dimensional solutions. That’s why Prague still has a soft night skyline from whatever angle. Moreover, the Czech Republic has held the world’s centuries-old leading position in glass making. After Mariánske Lázně, Trója and the Franciscan Garden in Prague, I was supposed to do Vyšehrad in 1990s, but that’s gone. The economic factor traded an artist for a multinational supplier of industrially, mass produced lights. I am not saying they offer irrelevant design, but such solutions are often completely lacking character, impersonal. Usually even lacking dignity. This was one of the reasons that ruined many glassworks.

BO: What were your sources of inspiration? For I can see Castiglione, Moore, Hepworth, Gabo, also Pantona or Noguchi. What strongly manifests in your work is rather incomplete lyrical, geometrical abstraction of a concretist or minimalist course and postmodern touch.

PL: As a student, I had a chance to visit Berlin, Amsterdam and Paris, too. Prague always had some exhibition of some current art glass. We were quite informed about what was contemporary. However, I can’t name some direct source or idol (Brâncuși or whoever). On the top of it, the Kautman’s school was deliberately non-masterful or even anti-masterful. He was always forcing us to be personal, to go our own way. So, the connections you mention are somehow congenial. At that time, design was only in its infancy, so our projects had roots in sculpture. My degree is called “Academic sculptor”. There was no degree for design. I don’t think there is a strict distinction between independent fine and applied art. It’s something that swings in between, as art historian Ľuba Belohradská says. And even if it’s commissioned design, it’s always atypical. Take for example Trója where you can see the signs of my minimalist approach, but it’s necessarily blended in the baroque ambiance. They can’t be contradictory. The sense of a place and of its natural entity (not only of material cultural history) and thinking of a continual change of environment have always been crucial for me. One fixed light that would work well with blooming pink trees or when covered with white snow.

BO: …so Baroque Minimalism just like we say Art Nouveau Baroque, just like in case of the building of The Academy of Fine Arts in Prague… or the music of Michael Nyman…

PL: …yes, let’s say. Moreover, on the example of Trója – you always have to tackle the whole context of things: the horizon of a place, individual vistas; historical buildings and its contents; the garden, two and more parterres, including magnificent orchards and vineyards; the open-air theatre with two stages and one auditorium, where some lights serve as the orientation lighting of broader entities, the others are used to spotlight objects, surfaces, facades and some of them are to light the ground to prevent the incoming actors from tripping on the steps; the height of lamps and planting (to keep in mind its later growth), maintenance plus linking it all with the neighbouring zoo and of course, the economic, technological, safety as well as ergonomic and ecological aspect. The concept of new Trója started to be drafted when it still was a complete ruin; tearing it down had also been one of the options. It was a great job built from the ground up that brought together the discussions of historians, architects, dramatists, gardeners, conservationists and artists. Of course, the split of the Republic also made it less and less possible.

-

Lighting at Troja Palace gardens, Prague, photo: archive

Associate professor, academic sculptor Peter Lehocký, Art. D. (born in 1944 in Drietoma, lives in Trenčín) finished the Academy of Fine Arts and Design, at the Section of Industrial Product Shaping under the lead of associate professor Kautman (1967-1973). His portfolio includes both public and interior lighting, glass and packaging design, sculpture, holography, drawing and painting (exceptionally), tapestries or devising graphic logos (a couple of times). Lehocký is a table-tennis aficionado. From 1986 to 2018, he was pedagogically active at the Department of Design of the Faculty of Architecture of the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava. Exhibiting around the globe, his works are to be found in many collections. Among others, he devised solutions for exteriors and interiors of the dormitories of the vocational secondary school in Stará Turá, the funeral home in Trenčianske Teplice, the Heavy machinery plant (Závody ťažkého strojárenstva) in Dubnica nad Váhom, the Institute for Education in Construction Engineering, the Fórum Hotel and Danube Hotel, Medical Gardens in Bratislava (which had been deinstalled and subsequently stolen), Mariánske Lázně spa collonade, the complex of Trója Palace and Franciscan Gardens in Prague or the fountain for Žilina city and many more.

Answered the questions of Boris Ondreička, artist and a curator.