Column / AGAINST THE AESTHETIC OF LOBOTOMY

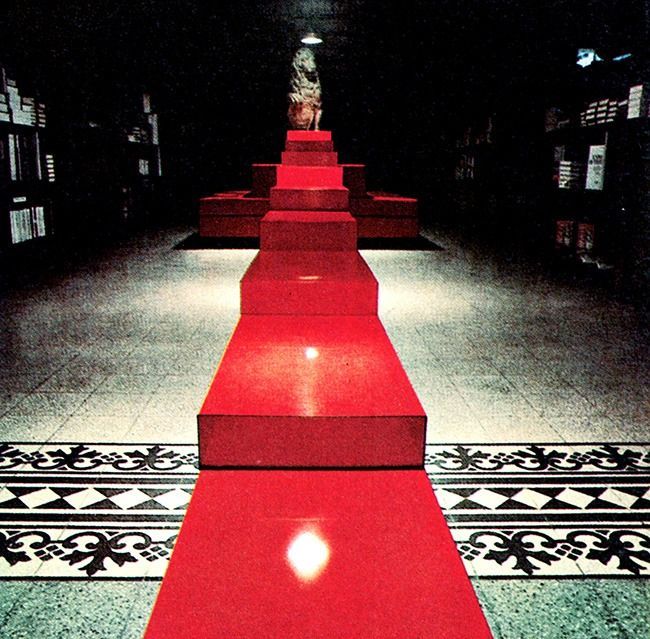

(Marzocco, Superstudio 1967, archiv Cristiano Toraldo di Francia)

If we look at the spatial production these days, it seems quite difficult to experience disturbance or shame. Joy of kind of beauty that feels almost embarrassing to admit. As Rem Koolhaas mentioned at the 2014 Venice Biennale Monditalia exhibition:

“In the Fall of 2006, I felt a sudden urge to revisit, or visit for the first time, the Italian Renaissance (…). By far the most disturbing space I experienced on this journey was the vestibule of the Laurentian Library by Michelangelo. This space was terrifying, almost like a nightmare. Nothing worked, everything was ‘wrong’.”

Architecture used to embrace these qualities quite openly. The violently lavish landscape of dark green structured marble and dark wood hidden behind the indifference of the Müller Villa by Adolf Loos. The crushing heaviness felt under the pyramid of Svetko’s Slovak Radio building. Dark metallic and glass clad corridors of the metro in Prague. Rich spatial and material vocabulary used to reflect the neurotic and perhaps decadent nature of our synthetic environment. Beauty used to be associated with such language of indulgence.

Contemporary spatial rhetorics could be described by the Google motto: “Don’t be evil”. Comfort is the ethos. Topics as fragility, material purism, cuteness, lightness, human scale dominate the mainstream discourse. Interiors are being refurbished either in cheap swarowski decor, mid century nostalgia, or clinical pseudofuturism. Modernistic estates are demolished and post modern facades lobotomised. The language of progress is not heroic anymore, because true indulgence is dangerous and danger is not marketable. You cannot make an ad for opium. In the quest for acceptable appearance, we are depriving ourselves of the rich, intense spatial experience. The vulgar, nightmarish horror.

However, such places of intense vocabulary do exist, if we look at the city more closely. In fact, they could be appropriated as a question of architecture. There was a time / link https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/nov/22/radical-disco-architects-italy-nightclub-design-60s-70s-ica /, in the 1960s, when Italian practices, such as Superstudio and Gruppo 9999 embraced the qualities of nightclubs for radical and vital architecture. Compared to this, OMA’s approach for the recent design of Ministry of Sound II / link http://oma.eu/projects/ministry-of-sound / feels as sensible as the marxism of Miuccia Prada.

What this shows is rather the problem of the architectural discourse. It still aspires to describe the city as an entity with homogeneous cultural values (identity), leaving much unnoticed and accepting the mainstream desire for lobotomy as a given reality. But these intense spaces are not ‘other’, they are not part of some ‘alternative’ universe, deep strata. They are here and crucial to everyday life and as carriers of certain aesthetics that has become disassociated with our environment as we think about it broadly.

(Biblioteca Laurenziana, Michelangelo 1525, Autor foto neznamy)