INTERVIEW WITH JOS BOYS

“There is no universal design, you can't build something that works for everybody.”

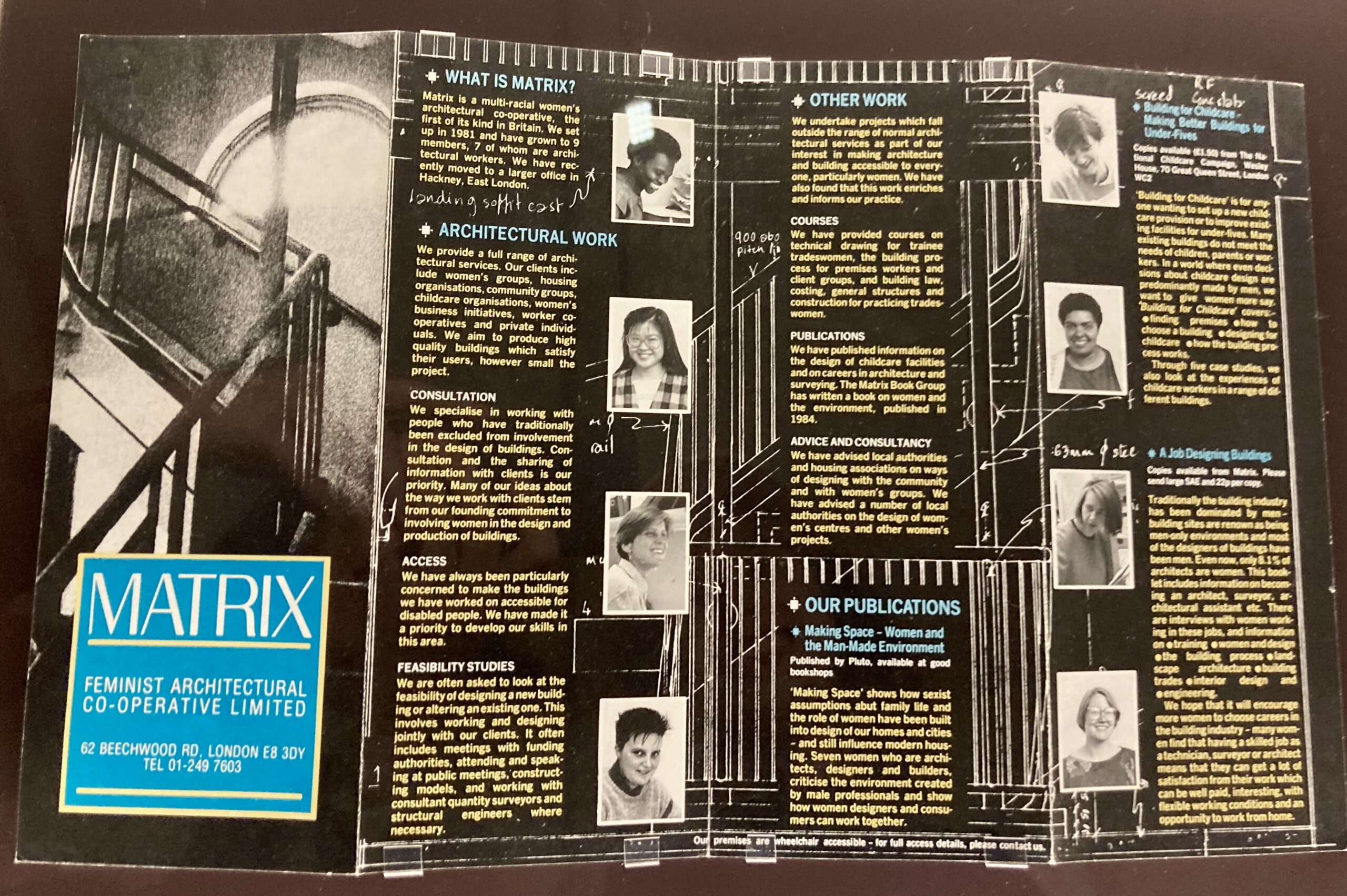

The profession of architecture has been disputed in the critical sphere for decades. Male-dominated, often precarized, profession that shapes our world seems to often neglect the needs of those who live in it. Jos Boys has been one of those who dedicated their work to challenge conventional architecture, by searching for alternative methods, re-shaping the discourse and questioning it in teaching. One of the founders of the Matrix feminist design collective, currently the co-director of The DisOrdinary Architecture Project, Jos explores the lasting problems of architecture, what feminism has brought to the field and where there is a potential for further change.

Spolka: Jos, you have been very active in the field of social change and feminism. Could you define your position on how architecture as a professional discipline can relate to social change?

Jos Boys: I call myself a design activist. I explore how to work with non-specialists in ways that open up the discipline’s assumptions about what makes a good building or public space. That said, I am much more interested in what makes a good life, and how our built surroundings can support that and diverse forms of occupation, centring on those who have historically been most excluded from design processes.

I believe social change happens through a kind of snowballing effect. This starts from changing the attitudes of a few, when considering the most disadvantaged is deemed avant-garde, until it multiplies and multiplies and becomes mainstream. If we value our bio- and neurodiversity as a creative generator rather than a problem for designers, and learn from our many different ways of being in the world, then we have the possibility of some innovative and exciting design shifts. This can start from the immediate – from small creative changes to everyday social spatial and material practices, based on the lived experiences of diverse people outside the norm.

Can you describe this immediate practice, an example of what would it be like?

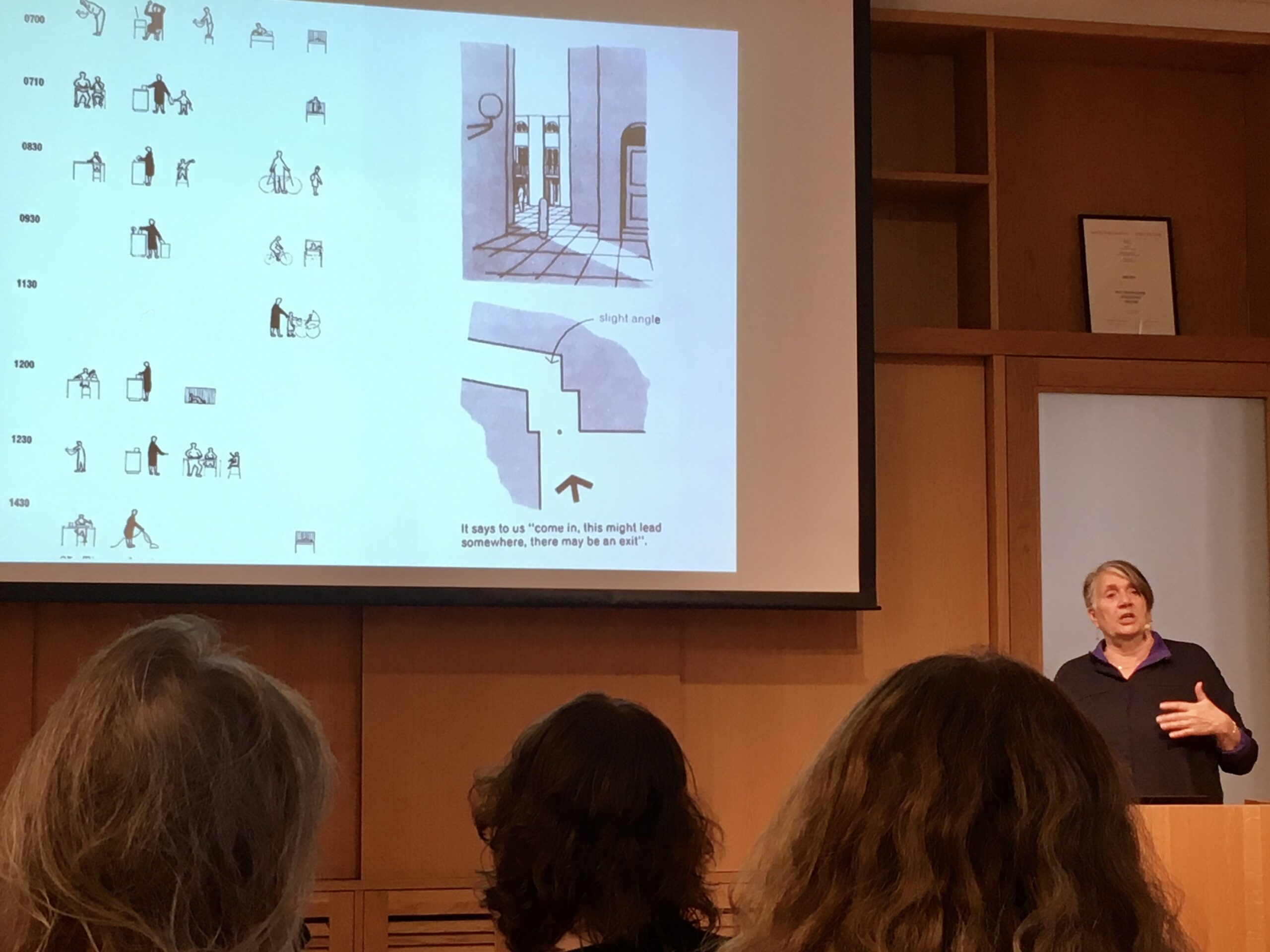

I’ll talk about DisOrdinary and I’ll come back to Matrix as well at some stage, but I think with DisOrdinary Architecture, an example would be Architecture Beyond Sight (ABS) – a foundation course for blind and partially sighted people who are interested in becoming architects that we run in collaboration with The Bartlett School of Architecture at UCL. It’s a very deliberate kind of challenge to the way that architecture normally works. Generally, it’s a very visual subject. There was and still is a very strong idea that disabled people can’t be architects. There are all sorts of barriers to becoming part of the profession if you have an impairment. For blind people, in particular, that seems like an impossibility. So, the aim of ABS is, first, to enable blind people’s confidence to design architecture, and, second, to showcase the quality of disabled creativity. Third, we want to develop alternative non-visual centered design methods, such as audio description, performance, large-scale embodied drawings and tactile sketch models. We want to offer other ways of designing beyond plans, sections and elevations, which are very removed from our diverse perceptions of the world , and our different social encounters with it. We are working with disabled people to explore methods that engage with all the senses, and that could also benefit mainstream architecture. We try to change the way that architecture is taught and practiced through these very small-scale waves.

How would this traditional perception of architecture differ from the values you are proposing?

I think mainstream architecture too often assumes an equality of experience in built space, based on “normal” bodies and minds that can go where they want, when they want. Once you start thinking about disability as a concept and disabled people as a constituency you can’t assume the agency of taking action or choosing what action to take, either as an architect or as a building user. Some people have agency taken from them, because of how their bodies and minds are perceived, or the kind of situation they are in. So, having ease of movement and agency for me is a kind of privilege that we need to take notice of. There is a critique in disability studies scholarship and activism around the notion of agency and about why we focus on that as the thing that we’re trying to enable. There’s a whole set of thinking around replacing that with the notion of human flourishing. How do we enable flourishing? And that brings a whole lot of connected ideas which are developed by disabled groups like the Disability Visibility Project and Sins Invalid in the USA around collective care and disability justice, as well as many others.

Let’s return, as you mention, to the practice of the Matrix. Matrix was a collective of feminist architects who brought issues of gender to the design of architectural practice in London in the 1980s. How can collectivity encourage agency to change?

You use the concept of agency again. For me, agency remains a term that is very focused on individual self-control and determination; on self-actualization. But if we talk about collective agency as the ability for groups to take action or to choose what action to take, then I think for Matrix it was really central to the design practice. The types of agency that were available both to Matrix itself and to the various women’s and community groups that it worked with was, of course, dependent on context; on the patterns of local government support and funding that underpinned the possibility of any change. But I do think that Matrix enabled, it really did increase the agency of very many women’s groups because it increased their access to resources and their control over how those resources could be used to support women’s needs. As well as undertaking feasibility studies that supported new and radical forms of childcare, for example, Matrix worked in equitable and participatory ways that enabled diverse women to better understand what kinds of built spaces they wanted and to co-design these spaces.

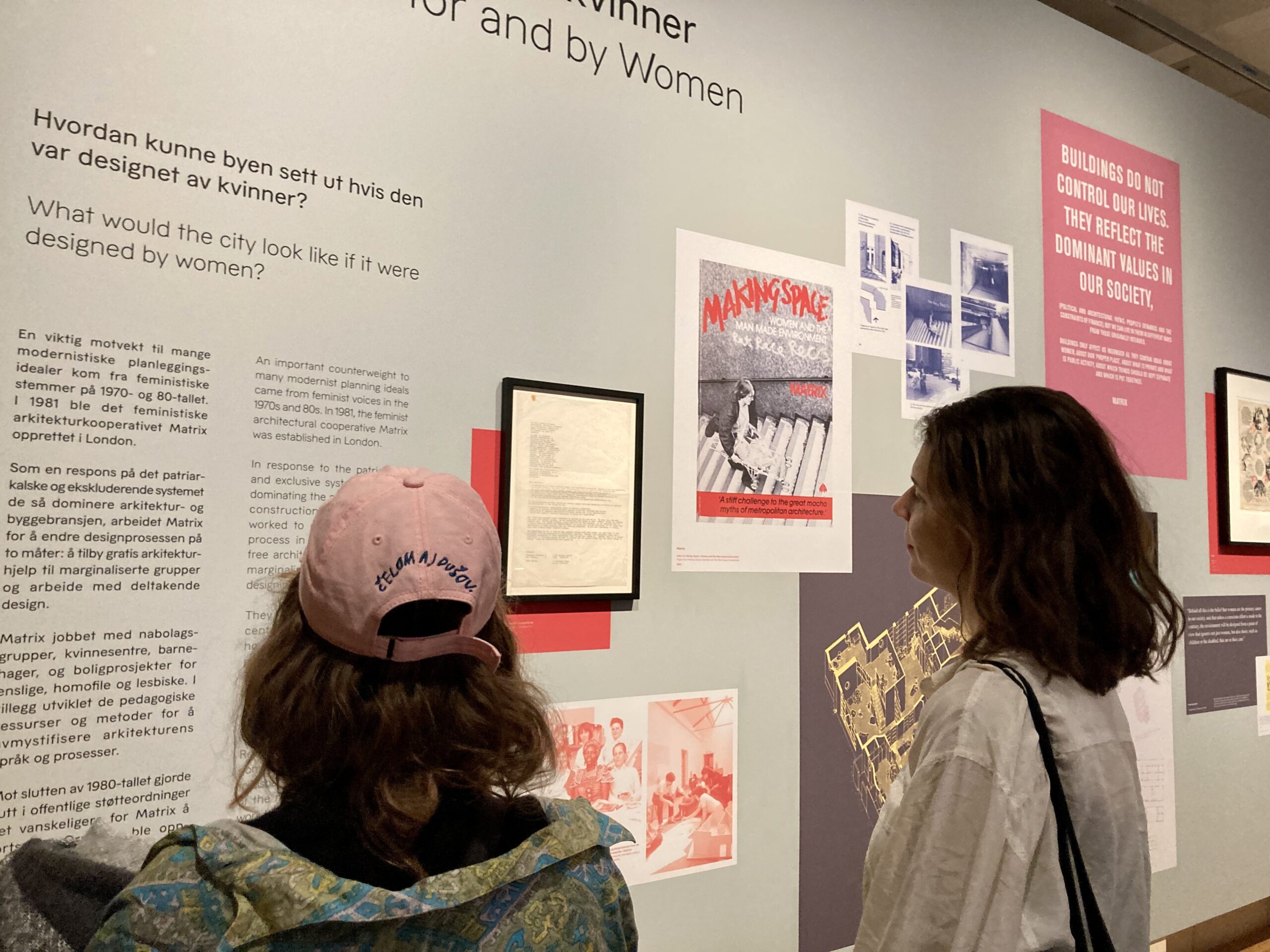

Matrix at Oslo Architecture Triennale – Mission Neighbourhood – (Re)forming Communities, source: archive of Spolka, 2022.

On Power in Space-making

And how would Matrix differ from the mainstream architecture at the time?

It’s going back to power and expertise. Like, what is our expertise? What is it that we’ve learned from the disciplinary practices that we’ve been educated in and involved in, whether that’s architecture or sociology, or any other related subject? Then, what is it to share that expertise or to use that expertise? In the Matrix book (ed. note: Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment from 1984), there’s a whole chapter on explaining how architects represent built space in a particular way, based on orthography, so that non-experts can understand what these diagrams actually mean. Matrix developed many techniques to help participants understand spatial design more easily, such as exploring scale by connecting whatever they were designing to the size and shape of the room everyone was in. I think that it still stands out as quite a radical understanding of participation – that you don’t ask people what they want and then design it, you actually somehow set up a process where you share and co-develop. In doing this, the architects still recognise their own expertise, but also give non-experts the tools to express their own expertise through lived experience. As a young person interested in a socially engaged practice both during and then after architecture school, there was kind of an idea around about community architecture that you could just be a neutral conduit – that people would tell you stuff, and you could just turn that into a design. And that would be exactly what they wanted, which, of course, turned out to be completely not the case. And I think that those really basic techniques for having equality of the tools that you’re using that Matrix developed, I think, it was very powerful.

When talking about equality, care and space, we also touch on feminist philosophy. Would the notion of feminist space-making work for you personally? Are there any typical features that are important for such space-making?

I really like the fact you call it feminist space-making because when Matrix was around we always got asked what a feminist architecture looked like. That you could give examples of a feminist style – probably that buildings would be round rather than phallically pointed. And it somehow always seemed a very unsatisfactory response to our audiences, particularly conventional architectural practitioner audiences, that a feminist practice was about the process rather than the product.

DisOrdinary emphasises a similar centring on the process rather than the end result. Disability studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson uses the concepts of fitting and misfitting. Rather than universal access “solutions”, built space is understood as dynamic and relational; we fit in some situations and not others. So, space-making is about understanding how power relations are played out across the material world, through how people fit and misfit. This is really valuable for rethinking assumptions about disabled and non-disabled people. But it is also intersectional – how we can misfit through, how spaces are gendered or racialised. And it is about space-making critically engaging with misfitting and then creatively exploring provocative and practical interventions that make it possible to fit – opening up new possibilities in how society could be organised, reframing what counts as fit.

Matrix at Oslo Architecture Triennale – Mission Neighbourhood – (Re)forming Communities, source: archive of Spolka, 2022.

The Path to “More Fitting” Architecture

When we look at the beginning of this all, how did you become a feminist architecture scholar?

Well, I wanted to do photography and they said I couldn’t because I was a girl and the equipment was too heavy, which tells you something about historical change. I never regretted doing architecture, although I knew quite early on that I didn‘t want to be a conventional architect. I was part of a whole new generation of young middle-class white women in the 1960s and 1970s in the UK, who came into architecture in much larger numbers postwar. Those were still quite small numbers in comparison to today, but there were enough of us to realise that the profession was inhospitable to women, as we experienced different degrees of misfitting, also entangled with race, sexuality and class. As someone with a non-standard middle-class upbringing, it was class, the gentleman’s club aspect of architectural education and practice that I found very confusing.

I can’t remember what the initial group that Matrix grew out of was called. There was a feminist collective and I remember there being a first meeting of, like, 65 women in London. We had very different attitudes about what feminism meant to us and what we wanted to do with our lives. It was important, though, just getting together and sharing experiences and recognising how these were based on systematic inequalities not individual inadequacies. For me, my main involvement was in the very early days of Matrix and as a co-author of the Making Space book. So, building on the whole feminist practice of consciousness raising as women together, but also undertaking research that could help us better understand how built space was gendered.

And what social conditions would you say enabled Matrix to constitute feminist architectural practice?

There was a particular political moment with the Greater London Council, under Ken Livingstone as Mayor, who wanted to really change and improve the built environment for non-normative groups. It meant that there was funding for women’s and community groups, which was essential to supporting alternative forms of architectural practice. At the same time, a whole set of things made it possible. We could live quite cheaply, a lot of us were squatting. We were learning building work by adapting the houses that we moved into. London was so empty and derelict. There were lot of community action campaigns anyway for trying to save parts of the city from redevelopment or to support working-class people in providing better housing. Nowadays it is much harder for people who want to work for change in somewhere like London because it’s very oversaturated with projects. There aren’t any more derelict buildings. It is very expensive to live here these days.

You mention contemporary social and political situation. How is it allowing the radical practice in architecture?

With The DisOrdinary Architecture Project, we’ve just won a project for the London Festival of Architecture with a group called Refabricate who focus on the waste economy. And it’s really fantastic. It’ll be really amazing to work with them. But almost everybody in Refabricate is in a full-time architectural job and the more radical work they’re doing has to be a kind of side hustle. And again, I don’t know what the situation is for you and for the different people in Spolka because what I’m doing is that I’m working with people who are trying to do something different in hard circumstances, including an increasing number of disabled architectural students and practitioners . Originally, when disabled artist Zoe Partington and I set up DisOrdinary Architecture (in 2007) we came to this idea that we would bring disabled artists in, because there were so few disabled people in architecture, as a way to co-explore disabled creativity across the discipline. It was also to intersect art and architectural practices, to open up for debate how architecture is taught and practised, and how it could be done differently. As part of that, DisOrdinary Architecture began to make safe spaces for people with impairments already in architecture, or wanting to study it. So, in parallel, and not just because of DisOrdinary, but also because of other disability activist networks and scholarship, more disabled creatives are now visible and vocal across education and practice in very exciting ways.

How would you describe the impact that diversity in architecture can bring in the built environment or in policy making?

I’m completely aware that increasing diversity is vital and that to actually change policy and practice around getting things built is essential. But we also need tools and tactics that don’t just “add” more diversity to architecture, but challenge its norms. DisOdinary Architecture has had a project floating around for a long time because we’ve never found any money for it. It is to do a kind of alternative building code, a beyond legal compliance publication, which instead of being just a lot of technical guidance with instant answers and very simplistic “universal” design solutions is an incredibly rich compendium of different and innovative ideas, led by disabled artists, architects and activists internationally who are already rethinking disability, access and inclusion. It’s like a rich inventory that you can flick through when you run out of ideas about accessibility; something that enriches your design, imagination and is not just a technical requirement that you add to a design from a standard template at the end of the design process. We are now producing a prototype called Many More Parts than M! Reimagining Disability, Access and Inclusion Beyond Compliance (Part M is the title of the UK building code on accessibility), which will launch in February 2024.

We are quite opposed to universal design, we work with the plurality of needs and thus have to ask. Do you think that there could be design solutions that could be universally accessible for all needs of all people?

There is no universal design, you can’t build something that works for everybody. There is no such thing, there are huge differences in people’s access needs, in our preferences and our roles in life. There’s a lot going on there and it just doesn’t make sense to aim for some sort of a single final answer. We need to have better co-designed ways of valuing the rich bio- and neurodiversity of both humans and non-humans. Also, to see that we all have access needs, it’s just that the conventional built environment only meets the needs of “normal” people. This means accepting that diverse access needs are intersectional, both across disability and between disability and other non-normative identities, and that these can both align and conflict. Design becomes about collaborating on a range of multimodal and equitable alternatives that allow for – even celebrate – different ways of being in built space. Which will always be a work in progress, uneven and unfinished. This means thinking about the design process in a very expanded way, based on multiplicity and adaptability –connecting into sustainability and the climate emergency. Not just building things and leaving, but a whole way of working based on adaptation, maintenance, care and repair – a process of enabling, that we will never get completely right, but need to keep trying.

Jos Boys during her talk about the Matrix collective at Oslo Architecture Triennale – Mission Neighbourhood – (Re)forming Communities, source: archive of Spolka, 2022.

Joy in the Making

Personally, I’m very academic, I even came into feminism from a kind of academic questioning point of view, wondering about how space was gendered, how it “worked”. And what needs to happen, to create more equitable spaces. It was a kind of curiosity that drove – and drives me.

And with disability, I realised that we’ve got feminist studies about architecture and the built environment. We’ve got some critical race studies, not much, but we’ve got some. We’ve got queer studies. We’ve got stuff about queer space and queering space. But when it comes to disability, there is almost a complete blank. It’s seen as ahistorical, apolitical, acultural, as just a functional and legal problem for designers, not as an area that can offer any criticality or creativity. Then I discovered disability studies and found lots of brilliant scholars out there, and disability activists and artists, whose work started from diverse embodiments and difference. And they were writing about disability, access and inclusion in very energetic, very angry ways. DisOrdinary Architecture has learnt so much from this. Everything we do starts from the embodied and experiential. We get people to move around a lot. We get them to invent spaces using their bodies. It’s very energising, it’s enormous fun and it’s a great way to think about access and inclusion, which is usually seen as very dry and boring. What we get is people just playing around with their bodies and minds. The aim is to show how nuanced our relationships to our bodies, minds, encounters and spaces are. By experiencing space differently – including being frustrated as well as finding new pleasures. Like, if you’re carrying a lot of things, you get tired quickly and it’s really hard to get through a door, but it’s also about the very creativity that it produces. Like when you work out, you can get through the door by using your knee.

That is a very nice example. Do you think that joyful methods themselves are also feminist?

I think joy is an important tactic. Finding methods that are themselves energising, just as Matrix did with some really enjoyable ways of explaining orthographic drawing techniques. Ann Thorne, a co-founder of Matrix feminist design collective, used to slice a cake into pieces, showing what its plan and section looked like. So, having these very inventive and enjoyable methods, I think is also part of how you bring understanding.

With regard to your time in the Matrix collective and our experience in the Spolka collective, what is your advice on how to maintain a collective life? How to maintain values that we translate in our work inside the collective and back to the practice?

Doing this kind of work is both very energising and joyful in terms of working with a range of people that are committed to the same things and where you can really work those things through, but it also does lead to burn out. It does get exhausting sometimes because you’re just fighting against or trying to resist normative ways of operating or you’re having to compromise with those ways of operating, which can be both valuable, but also quite tiring.

What were the most present obstacles for the collective work in Matrix?

With the change of political power in the UK into the 1980s, with the Conservative party under Margaret Thatcher, a lot of the opportunities that were open to Matrix began to fade, such as the funding streams for feasibility studies. Before, we could work with women’s and community groups on what they might like and actually help them get their funding and increase their ambitions. Then London-wide funding was cut and it became the responsibility of individual local authorities, who had much less money. There were times when it was really tough. And it’s also possible for some people to do poorly paid radical work and not others. Matrix had a principle of paying everybody the same and that worked for many white middle-class women, who didn’t have debts or financial responsibilities for others, but for some women it wasn’t possible to be part of the collective, or they had to take on two jobs to survive financially.

Are there any strategies that could contribute to healthier working conditions in architecture?

I don’t know whether it’s true with you too and across Europe, but there is a whole movement in the UK at the moment to unionise architectural workers – through the Section of Architectural Workers (SAW), part of United Voices of the World. In a way it’s what the New Architecture Movement – one of the forerunners of Matrix in the 1970s – also did. It is bringing the importance of being in a collective of workers to a profession which remains based on a very strong competitive and individualistic and obsessive element; which in turn justifies low pay. So, the idea that people can actually come together to resist low wages and very long working hours is being revitalised again in the UK, which seems to me to be really valuable. And it is done very explicitly. It’s not just about pay, it is about shifting the capitalist models of mindless productivity. So, I’m very excited by that and I think that’s a key way forward.

Spolka and Jos Boys during an interview in Oslo, source: archive of Spolka, 2022.