Through the City / A SPACE FOR LONELINESS

They were my alibi from the gaze of others

One day I decided to return two dozen books to the Spolka’s library that had miraculously found their way into my home. I had only read one of them, the others had come to me for fear of other people’s stares.

It started with the habit of going out for coffee with myself after a day’s work and aimlessly observing the happenings around me. Instead of observing the world unnoticed by others, the target of my attention often became me – a young woman sitting in a coffee shop alone – with no friends, book, headphones, computer or cell phone (the latter is almost always dead, so it can’t provide me with the fictitious charm of busyness). With nothing and no one beside me, I felt naked in front of people. In Slovakia, you don’t often see people sitting alone, without a computer or someone arriving soon. So I started taking the lightest and smallest books from our office with me. Behind each one, I just idly read the abstract and sat lazily in between, watching the world go by. Behind the book, I felt like I was behind the miraculous shield of another person’s presence (present, admittedly, only in the lines of the book), no longer sitting alone, and all was well at once. I usually brought the book home afterwards and left it forgotten on the table. Each one met a similar fate; they were my alibi from the gaze of others.

Author: Kristina Roman.

Loneliness in the city is growing

Increasingly, I come across claims in literature and professional debates [1] about how the urban environment, its atmosphere and particular attributes affect not only the physical but also the mental health of society. Loneliness is not a new phenomenon in the context of urban policy-making; it is a growing problem globally, and in our region, influenced by capitalist individualism, all the more pronounced (as reflected, for example, in the ‘zero loneliness’ vision of some British cities [2]). At the same time, the recognition of the costs of loneliness in the context of public finances and public health is a relatively recent phenomenon: loneliness and isolation pose serious risks to public health – they are associated with obesity, heart disorders, physical inactivity, mental health problems and other health complications. In some countries, such as the Nordic countries, the UK and Japan, the risk can reach critical levels. I was therefore interested in exploring the link between loneliness and public space.

Urban planning is often about trying to reduce the subjective feeling of loneliness through more opportunities for social interaction in public space, which can also be observed in Slovakia (for example, just by looking at the number of competitions announced for the creation of public spaces). In response to this, urban design focuses primarily on the design of parks, squares, cultural institutions that bring people together in public space. However, these designs tend to promote sociability among already connected people and do not address the social needs of lonely people, who are often put off by the presence of other people in public space. Attempts to eliminate loneliness may even exacerbate it; conversely, creating more space for loneliness may, according to recent studies [3], alleviate its poignancy. A related issue is that there is generally little space in public for people to feel uncomfortable, with loneliness tending to be one of those uncomfortable feelings. A wide range of other experiences of loneliness and isolation are also neglected, not just those related to social isolation and lack of contact with others. Loneliness can be caused by deep internal traumas, dissatisfaction with one’s life situation and other individual reasons. It can cause lonely people to feel that they do not fit into social norms, which can result in limiting their stay in public space and also in limiting their ability to develop their belonging to a place or community.

This is not to say that urban design, which aims to promote social connections, is not useful in the fight against loneliness. It is about its diversity. Many lonely people prefer to spend time alone because it helps them reflect and cope with their negative emotions and experiences. Importantly, however, not engaging in social activities does not necessarily mean that an individual wants to withdraw into their home (if they have one at all). Ideally, a city’s infrastructure should offer opportunities to connect while living comfortably side by side, but alone. The city should serve as a platform for emotional self-regulation. [4]

Being single

Photo: Kristina Roman, 2021.

Low visibility of loneliness can signal that feeling lonely or wanting to be alone is unusual or unacceptable, which can only increase loneliness. The design of a public space should therefore encourage people to use and visit it, so that they can also be alone. One tool can be, for example, furnishings that are also designed or adapted for individuals and can therefore visually normalise loneliness. While park benches emphasize the non-normativity of sitting alone, solitary seating does not signal the absence of others. [5]

With this issue in mind, the city’s design should convey a message of acceptance and safety to people experiencing loneliness. It is also about safety in the sense of the social safety of public spaces, where one might not feel negatively evaluated and rejected because of one’s loneliness. The solution lies in urban design and public policies that take greater account of the needs of individual users. An important part of the transformation is the push to create places for individuals also in civic facilities, cafés, other places for eating, etc.

Photo: Kristina Roman, 2021.

For example, I often feel too visible or exposed to the gaze of passers-by in public spaces. For a person who gets easily exhausted after interacting with other people (even just passersby), this is challenging. For me, loneliness is associated with shyness, irritability, and social anxiety. Unpleasant exposure can be prevented by plants, different types of vegetation, small architectural interventions, safe nooks and crannies, and urban furniture that signals the right to sit alone.

Sitting alone

The only public place where I feel like myself is a cemetery. There no one will judge me for the sad look on my face, or for doing nothing and being alone. I never hear a disrespectful remark. I sit alone and no one comes near me. People respect each other here, they like each other a little more than in the city. I feel safer here.

You will rarely find just one chair at a table in a café or restaurant, and there are no reserved seats in public spaces for single people. Seating tends to encourage sociability. In many ways we are used to being together, just not in our solitude.

Sitting alone, which implies a quick snack and moving on (e.g. in a café or at lunchtime in a bistro), is a fairly common practice and the stigma in these circumstances is not perceptible or outwardly visible for most of us. However, as soon as there is a demotivating and sustained enjoyment of one’s own company, there is a significant change in the perception of such an experience. The absence of tables for individuals in the restaurant suggests that being alone is unusual and undesirable in this setting. The status of a single person who is not in a relationship (voluntarily or involuntarily) and functions as a loner for long periods of time is not part of the generally accepted order of things. However, the stigma of singleness seems to extend beyond relationship status. After all, being out in public with friends is usually just as acceptable as being with a partner or family. For example, people who want to dine alone may feel uncomfortable and therefore be less likely to come and stay. Observing another individual who seems content to dine alone can help to understand that the absence of a partner is not a negative experience. The element of solitary seating, although spatially invisible, is an ideologically important element. It will signal to the system as a whole that solitude is also accepted and welcomed.

Sitting in parks can be seen as places of self-care and connection with nature. They allow one to sit and observe public space without actively interacting with others. In reality, however, there are relatively few spaces where one can be alone. With a few exceptions, such as public transport or libraries, the concepts of ‘public’ and ‘solitude’ in architecture are usually seen as opposites. Public space in cities is largely defined by its spatial characteristics, but also programmatically for gathering rather than spending time alone. [6]

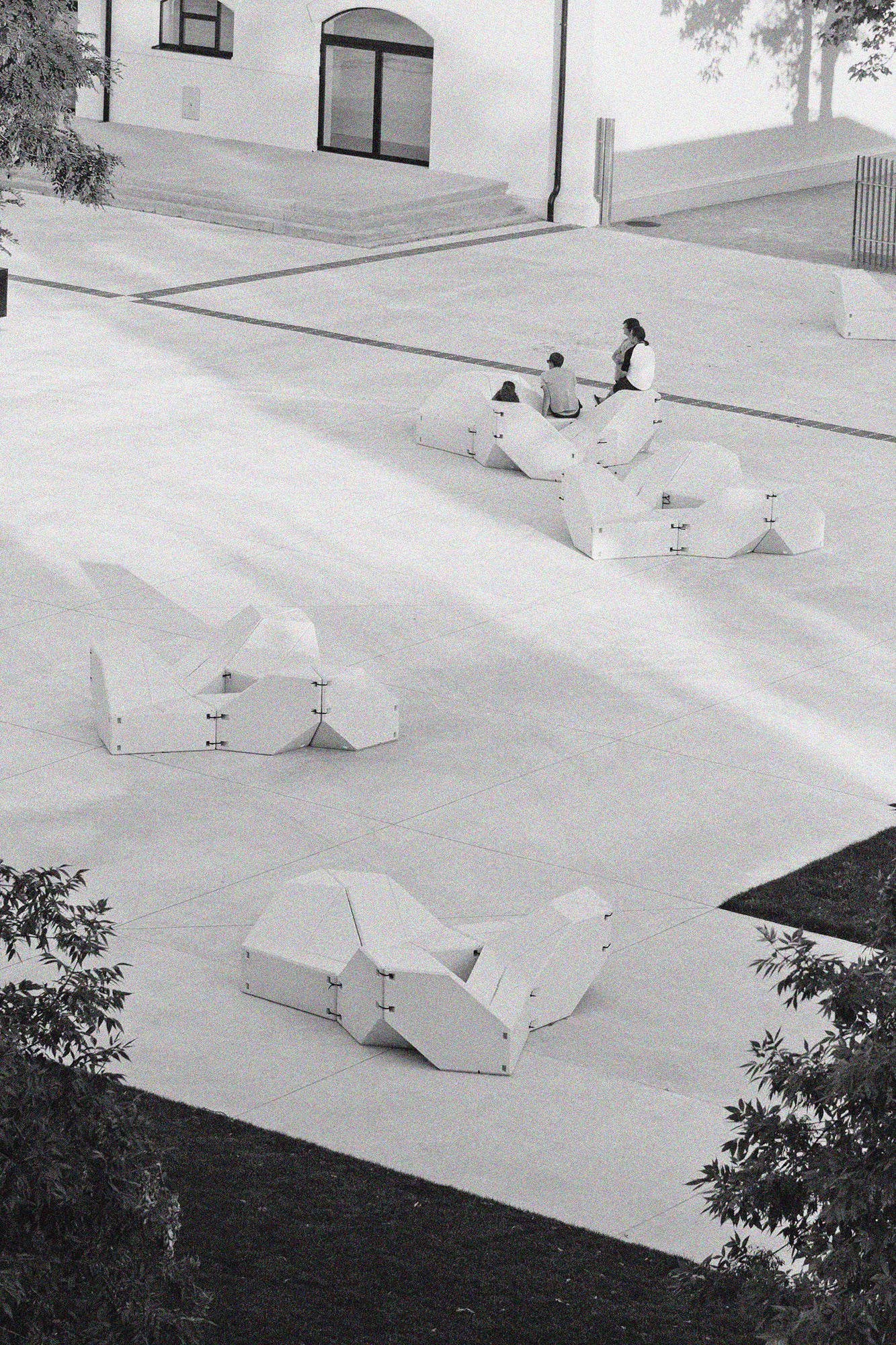

Kulturpark, Košice, photo: Ján Tekeľ.

A positive example is the urban initiative Sadni si! [Sit down!] in Bratislava and many other similar projects in metropolises. In Vienna, for example, there are sofas in front of the Museumsquartier, which do not have a strictly defined way of use – whole groups can sit on them, or individuals can lie on them. Similar furniture can be found in Slovakia in front of the Kulturpark in Košice. In line with this principle, Starbucks offers round tables rather than rectangular ones, which define the number of people seated more clearly. Even such a small change as the seating typology can manifest and change the issues of loneliness and solitude, creating the prerequisite for a more favourable and sensitive future.

Being vulnerable

The feeling of loneliness is familiar to all of us, but some groups are much more vulnerable to it. Often these are groups that do not have active tools at their disposal to combat loneliness. This is due to the increase in the number of elderly people, or also to intensive urbanisation and modernisation. Another important finding is that higher levels of loneliness are observed in lower income or stigmatised groups. Many studies, as well as personal experience, argue that women who enter public space alone are stigmatised more strongly than men.

Conversely, people who can afford paid services have more opportunities for social interaction and participation, and are less at risk of loneliness. Other protective factors, such as large household size, strong family ties, friendships, marriage and good health, reduce people’s vulnerability to loneliness. While loneliness at home is another topic for discussion, it is important to at least be aware of the link between the atmosphere and circumstances in the home and the opportunity to interact in public spaces. Particularly for older people, household composition is a strong predictor of loneliness, compounded by the fact that aging residents have a smaller radius of action and are therefore limited in their mobility and ability to interact socially [7].

Another characteristic of mobility that includes the opportunity to socialize is walkability. People who live in walkable neighborhoods are more likely to participate in events, know their neighbors, and be socially engaged. Residents of walkable green neighborhoods have more social interactions and are less prone to loneliness than people who live in less green neighborhoods. Particularly for vulnerable groups of people, neighbourhood social cohesion is an important indicator of life satisfaction.

Conclusion

I like to leave messages on traffic lights for other people. I also like to read them. They help me not to be alone, to communicate with people without actually speaking to them.

After reading the text, one might think that I am exaggerating a problem that is not so well-founded. However, when one starts to look at the city through the lens of loneliness, one will find that loneliness may be undesirable, or at best unacceptable, for the city or the people living in it. Loneliness comes in many forms and does not always mean being sad and crying, but also being at peace, observing, enjoying one’s own company. We fight loneliness unconsciously, almost like death – we avoid talking about it, we confine lonely people as far away from parks and squares as possible behind the walls of our apartments, institutional facilities or in virtual space. It is as if we pretend that loneliness does not exist, and so a city adapted to happy and sociable people acts as normality. In doing so, loneliness is felt by each and every one of us. We can argue that loneliness is as much a part of the human experience as joy or sadness. It is experienced by most of us at some time in our lives, and is common to people across cultures. Overall, however, there seems to be a disconnect between what many people who feel lonely need and what urban design offers and communicates.

It is important that we move towards a more diverse understanding of loneliness and include in our planning, among other things, spaces for solitude, spaces for observing others, and various small additions to urban furniture that allow users to engage interactively with their environment. The role of the city is to offer all its inhabitants a safe space that reduces social stigma. A sense of belonging can be fostered by design solutions that create space for solitude as well as various integration initiatives. These can be, for example, the possibility to exchange information with others through graffiti, artistic interventions or posters, or the possibility to participate in social and cultural life without an input investment (free film screenings, concerts, etc.) It is important that each of us has the right to feel loneliness and not to be alone in it.

Author: Kristina Roman.