Close Things / JANA BODNÁROVÁ

Closeness woven long ago

In the 20th century, our world changed profoundly and suddenly. All the more precious are the threads that connect us to what our loved ones lived through – so long ago yet so recently. The linen ones and the imaginary ones.

How far will the close thing you chose for our interview take us?

I’ll start by saying that I was born in an almost archaic village, in the 1950s. It was a setting where the village people were still mixing almost pagan customs with the ideology that the new regime was trying to get into their heads.

I remember many details from that time, for example, that women wore headscarves. Even inside the mostly wooden houses at that time. Untied, just draped over their heads. Obviously it was related to customs, tradition. Many probably didn’t even think about it. They had caps under their scarves, it was like a canon, especially the old women in those 50s. They mostly made the caps themselves.

My paternal grandmother and grandfather were small farmers. They worked a lot on their own, too. They kept sheep, so they knew how to process fur as well. And they grew flax, among other crops. The scenes of them drying the flax, breaking it, spinning it into threads, then weaving and sewing it into linen fabrics are still quite vivid in my memory. This hat belonged to my great-grandmother, and it is possible that she made it herself from the flax she also grew and processed. I was fortunate to still know her because she didn’t die until she was 98 years old.

The whole continuous process from the sowing of the flax seed to this object is an amazing spectacle – from the ground up. In today’s world, for most of us, something we can hardly imagine anymore.

It is indeed an ancient, twisted world – but for myself it is not somehow extremely distant – I still carry it in my memory. I lived in the aforementioned village for a short time, some seven or eight years, but really intense for childhood experiences. It was a village under the Liptov part of Tatras, quite cut off from civilization.

The villagers went shopping a couple of times a year in wagons to the city, but otherwise they were quite self-sufficient. They bought flour, sugar, salt and some mixed goods, which he also ordered, at the shop my father owned. As for food, they provided much of it themselves.

Back then they were still living in complete simplicity. But despite the modest conditions, women still adorned themselves a little. For example, I appreciate the element of femininity in their hats, which is also present in this simple cap.

They wore their costumes on some ‘big’ days; they commonly went about in blue or black garments. I remember old women sitting outside their houses. I rarely saw the aforementioned costumes on them. They weren’t even very ornate, probably because it was a poor village. My great-grandmother wore this cap – as she called it – which fits me exactly too. This physical sameness of our heads is a pleasant thought for me.

And many years later, this cap from a forgotten Slovak village made its way, imaginatively, to London. What is the story?

I was in the Barbican once and saw an amazing exhibition by the Chinese artist Song Dong. It was made up of thousands of objects that his mother had collected over a lifetime. She didn’t throw anything away, she also collected washed-up soaps and then tied them up in little clumps that she still used. Anything she could get her hands on in her life, she put away. It wasn’t a mindless obsession with things. In the era of her youth, she had experienced great misery. The fear of it remained in this woman permanently. And this, this “dump,” was put on display by her son as a huge installation. That’s how I was introduced to the Barbican and then I watched this cultural space on the internet.

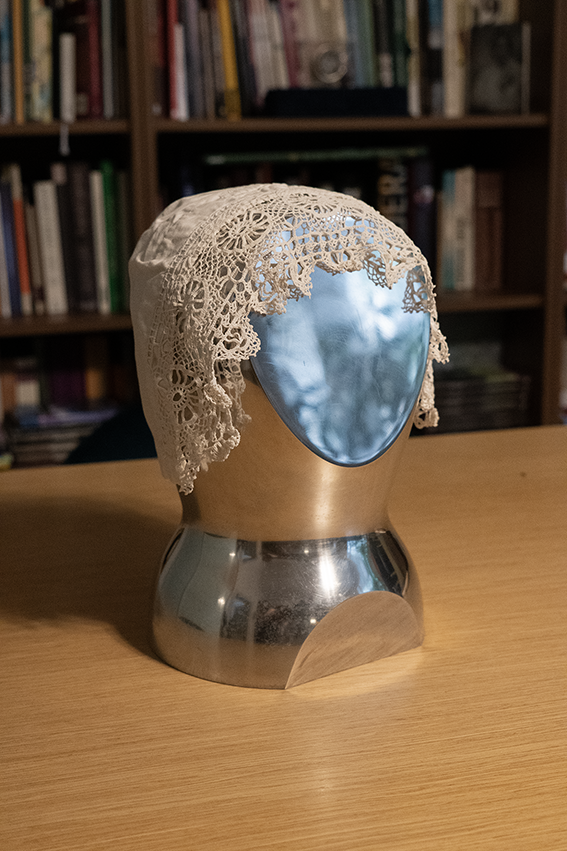

One day they put out a call for people to send them photos of objects they love, and write a short text about why that is. I wrote specifically about my great-grandmother, who was also an herbalist and therefore considered by some villagers to be a witch. Also, how I treasure a hat from her that reminds me of her. Then I photographed the cap on this aluminum statue of the Cosmic Head of Juraj Bartusz, my husband. It seemed like an amazing and multi-dimensional contrast. Of meanings and materials.

As if it couldn’t get any bigger, but at the same time it’s strangely harmonious.

Yes, in a way. A human object and an anthropomorphic sculpture.

So your great-grandmother was an herbalist. Do you know anything more about that?

She made various teas. For common ailments. She wasn’t particularly skilled at it, she didn’t make any salves or tinctures. She just gathered herbs that grew in the beautiful meadows, and that other villagers seemed to know. She collected plants for a very long time, until she was very old. My children sometimes said to me, you have a great-grandmother witch. It’s true that she had such piercing eyes, it was as if she could pierce through them. Or see something of substance.

How did this cap come to you?

I asked for it from her. She had quite a lot of them. But none of them were the same, each one had a different lace, with a different pattern. The caps were a kind of bottom layer. I remembered that the women put scarves over them, and the only thing you could see over their foreheads was the lace decoration. When caps were no longer worn, women often wore just scarves on their heads – untied, especially in the summer. I haven’t looked into whether this is related to any deeper religious layers, as with women from other religious cultures.

My great-grandmother was, is…a woman of our bloodline close to me, so it has a lot of emotional power as well. This simple thing makes her very present to me, even after many years.

Has it inspired your own writing in any way? If not in a completely straightforward way, perhaps in some bottom layer?

I can’t say that it was overall, but in Tiene papradia [Shadows of the Fern] I explicitly targeted her. What I knew of her, how I felt about her, remembered her…how, for example, she used to dip my bread in water and sprinkle it with sugar, which was the biggest treat for me. The way the children screamed you have a great-grandmother witch – and it made me, as a child, feel funny in a strange way. Those piercing eyes of hers! Then, too, the fact that she knew the power of herbs.

Tiene papradia is the story of an environmental journalist who travels to see the rainforest as she remembered it from the archaic village of her childhood. The journey evokes many memories… Just and of her great-grandmother, the alter ago of my great-grandmother.

My mom and dad were busy with business, so they didn’t have much time for me. So they used to put me in her care. And she, when she was tired and wanted to be away from me, she used to give me poppy seed decoction to make me sleep (laughs). I say I’m a “junkie”, abstinent since childhood.

You are perhaps the first person I know who has experienced this old “soothing” method first hand.

And I slept exactly as much as she wanted. She was able to work this out exactly. But then I didn’t sleep at night, my schedule was reversed. That’s how even my parents figured out what my great-grandmother was doing to me. And I was definitely affected by the fact that I was given “opium” for a couple of months. And perhaps later, indirectly, it affected my nervous sensitivity as well as my creativity.

Great-grandmother was a prominent figure in the village. She was simply different. Very distinctive. My great-grandfather and her husband were in America for a time. He worked in the iron works, where he died. She lived on her own from a young age, raising two daughters.

Do you have a photograph of her?

I don’t have any. Only occasionally did she appear in some group photos – miniature ones, on photo paper with a serrated edge.

And do you remember what she looked like?

She lived and died sort of unnoticed, quietly. Only those eyes, vivid, penetrating, remain in my memory. She had narrow lips and a very wrinkled face. She died when I was already in high school, attending the gymnasium in Liptovský Mikuláš. One day I met an older sister who told me that my great-grandmother had died a few hours before. I remember how I fell into a deep crying right there on the street. I felt terribly remorseful because the day before my mother had told me that great-grandmother was not feeling well. I should have taken her an aspirin. That was the cure for everything back then. I refused to go because of homework and studying, so my mom took the medicine to her. To this day, I’m very sorry about that. I lost my last touch with her. So at least – when I occasionally pick up this cap, it’s like a fleeting caress.