Conversation / DEAR ANNA, DEAR DANICA

Anna Cséfalvay and Danica Pišteková, two members of the architectural studio WOVEN, have a continuous (e-mail) dialogue about things between themselves and architecture that are timely for them. The first part is about producing and questioning.

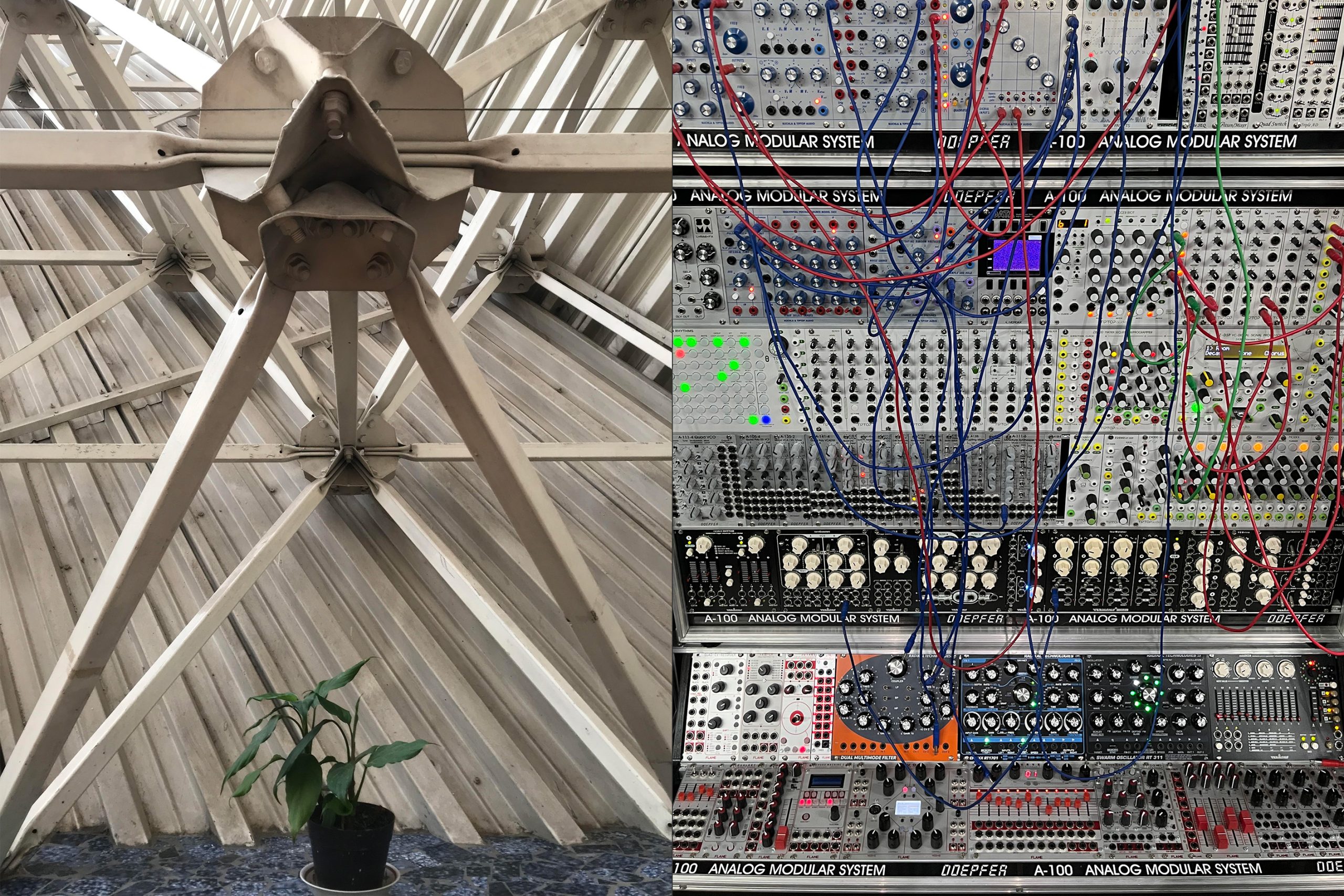

01_structure, source: Anna + Danica.

Anna, let’s talk about what we’d like to do, what kind of things we’re interested in. We could define our future direction in architecture, however broad our definition of it (fortunately) is. We’re women between 30 and 40, probably not “junior” anymore, but we’re also scared to start something completely new and somewhere completely different. I’m wondering what all this debate could contain, or what its goals are. Maybe through it we will redefine what architecture means to us now. Maybe we’ll talk about concepts, scales, materials, haptics, or working in the workshop. Maybe we will be interested in feminist perspectives, because although we honor them, we have never intentionally defined them for ourselves within the profession. Perhaps it will be a journey of self-discovery and rethinking without clear conclusions (because, after all, we know ourselves), but full of new, interesting and fulfilling questions. So who are we really?

Danica, I have been thinking about your words and questions for a few days now. Just last Friday I had an interesting conversation over a beer with one of my bosses. He divided creative people into those who produce and those who question (generators and contrarians in his words). He complained self-pityingly about the other boss, who he said liked to disagree with everything at all costs, and stated that while it was intellectually interesting to always and everything question, without the generators – and here he was implicitly referring to himself – nothing would ever get done. Whether I agree with his theory or not, I started thinking about us or WOVEN, what positions we fill, how we work together and how different we are. Also thinking about how frustrating it can be at times, but also how it is these difficult debates that move us forward. I realize that we also function autonomously as architects, educators, or friends, partners and mothers, but all of these roles are contextual and changeable depending on the environment. And so I ask myself and you, doesn’t who we are depend on who we are with?

Anna, I’ve been thinking about the contextual nature of (architectural) positions and I don’t know if (their) mutability is a measure of high flexibility or an inability to stand one’s ground. Or the other way around: whether the variability is a matter of fixed character and opinion, or whether it is an inability to step out of one’s comfort zone. When you’re with someone who is different in opinion and outlook, that’s when I think you really realize who you are and what you want, and what your positions actually are. Like one year at CE ZA AR (Slovak Chamber of Architects Architecture Award) for example, when the “gentlemen architects”, even though no one asked them, lectured us on how to do “great architecture” so that we could really understand “what it’s all about”. That pisses me off enough as it is. But also that the “real” architecture is supposed to be “big”, like when an acquaintance on a train once asked me a long time ago if I was doing a skyscraper for my thesis. And in doing so I was addressing the Smallness Manifesto, XS architecture and how (architectural) thinking doesn’t have scale. You talk about producing and questioning as opposites, do you think questioning is unproductive?

Danica, I’m wondering about the unproductiveness of questioning, and if we assume that being productive is from the word product, it could be said that questioning in some way slows down the process of getting results. However, this would have to mean that architecture is only a product and not a service (from the word serve). You know, the height, price or floor area of a skyscraper is quite easy to measure, at the same time it can be nicely photographed – but no one has ever won an architecture award for a well-asked question.

I, however, like to tell myself that as a licensed architect, I have become an author of services. Otherwise, service is defined, among other things, as work that does not result in a product. To be honest, I aspire to be much more progressive than productive; but I do believe that through critical observation we can create value on multiple fronts. After all, thinking is perhaps the only way to dream up alternative scenarios (and scales), which we probably need more than anything else in our current state of skepticism. Or do you think artificial intelligence will do it for us?

Anna, I think the product is one of the communication tools of architecture. But it evokes for me something finished and unchanging, something that is used, that serves. I’m more interested in comparing architecture to a labyrinth that always makes you think and experience rather than use. Experiencing even uncertainty (am I outside or inside? in an enclosed or open space? where am I actually?) is much more valuable to me than the desire for instructions, explanations and permanence as such. That’s why I think of architecture as a culture, a value, or an autonomous way of thinking, perhaps just of situations and scales, as you say. AI is already generating alternatives, but (for now) it is still us who translate and interpret its images. I find it interesting precisely in the debate with it, in the search for the limits of this debate and “negotiation”. I see it as a good opportunity to define what it actually means to “think architecture”, what is the language of such thinking, as new factors come into play, input data – prompts – as instructions in the form of texts or images, which is a different way of communicating and arguing. And in general – can we experience AI? Can we experience along with AI? As Monika Mitášová once said: “Someone had to live those data”. In the studio, we also talked about this with the students as a layering of memories. It could be a kind of memory glitch, not only in relation to an image that connects different databases, periods, eras or styles, both artificial and natural, but also to one’s own or social memory (I associate something with something, something comes up, I remember something clearly, I forget something, something connects wrongly, incorrectly, bizarrely), and such an element of temporality or even spatiality could be akin to surviving in or with AI.

What do you think all this might have to do with materiality or even the hapticity and sensuality of spatial/architectural experience?

Danica, I’m glad you outlined hapticity because I’m currently fascinated by the theory of embodied cognition, the basis of which is that our consciousness is shaped by aspects of the whole body. Just as who we are depends on where and with whom we are; our cognition is very much intertwined with the physical experience of the material environment. Thus our memory remembers not only images, events and feelings, but also sensory and motor systems – from breathing to recognizing objects that I can sit on, even if they are not shaped like chairs. I feel that it is this kind of unspoken knowledge that the AI lacks, and so relies on the experiences of other bodies. Just think of all those generated hands and fingers here!

The word “architecture” is often used in other disciplines to refer to systems, the logic of relationships, and the structure of objects, most often data. These are concepts of ordering that are largely influenced by our bodily understanding. For example, in probably every culture and language, “value” rises to a high place, while “low” evokes something drawn to the ground. I am interested in how such architectural thinking operates in architecture itself, where many layers of concepts, forms of physicality and corporeality intersect. Perhaps architecture can only be experienced when you are present in it. But what does presence and regionality mean in a world where our bodies are interconnected, enriched and expanded by new dimensions, often without horizon? And do you think the softness, fragility or finitude of spaces needs to be redefined in a new context?

Anna, it probably needs to be redefined anyway. It seems to me that the return to analogue, handmade crafts is huge today, and certainly intertwined with current technological possibilities. I’d like it if AI didn’t just generate a series of results, but also different processes or methods (of design, discovery, interpretation). For materials, for example, new recipes for making them, combining different previously unthinkable “ingredients”, where it would draw on a broad database of their properties. A cookbook of experiments, hybrids, speculations – such a bestiary. Today, it turns out that contemporary themes and issues such as ecology and sustainability, post-human strategies, or issues related to post-anthropocentrism and feminism are also communicated through (new) materiality. This seems to significantly derail entrenched views of architecture, especially those of the more privileged (white males) – see Schumacher’s Facebook post about the ongoing Biennale. It becomes more communal, without hierarchies, often temporary or even degrading, subject to change, weather or other interactions. Is it this new fragility/softness that so derails them? Or the loss of control and power? Thus, even creation itself is no longer based on the act of a sovereign individual, but on a process with many actors and forces involved in shaping their environment and each other. I think that alternative bodily spaces thus no longer emerge as traces of effective movement, but as envelopes of rich interactions. They no longer serve our bodies in the typical Neufert diagram of (seemingly) ideal kitchen counter heights, workbench heights, or appropriate windowsill heights in a near-sterile space that minimizes wasted energy and greatly eliminates friction between humans and their environments.

02_language, source: Anna + Danica.