Essay / ON THE ILLUSIONS OF PERMANENCE

A walk to Dana Tomečková's thinking

The history of human thought offers us many descriptions of the nature of our reality and the things in it. This special nature materializes depending on the perspectives from which we look and the tools we use. Let us walk together along a slow path, at the end of which Dana Tomečková’s perspective is revealed to us. Her artistic thinking is directed towards this very question, with intuition and metaphor as her basic tools.

Let’s start with the ancient past, around the sixth century BC, namely, ancient Greece. “Things change one upon another according to necessity, and are just to one another according to the order of time.” So went the famous statement of Anaximander, which was followed by all of modern physics. On the face of it, the simple statement represents two moments in the nature of our reality. The things we observe in it change, one becoming the other – transformation is thus their fundamental constant. The plant, slowly dying, has gradually decomposed in the soil. With the new arrival of spring we meet it again, but in a slightly different form. Yet it is still somewhere “here”. Things persist but change – this is the first moment that complicates our reflection. The second part of Anaximander’s theorem shows the dependence of things on time, which is structured – we know that something began in the past, and that something can no longer be changed, as opposed to something that is yet to exist. We, as humanity, have “rewritten” this peculiar structure into clocks, which have made it possible to measure the aforementioned mutability of things.

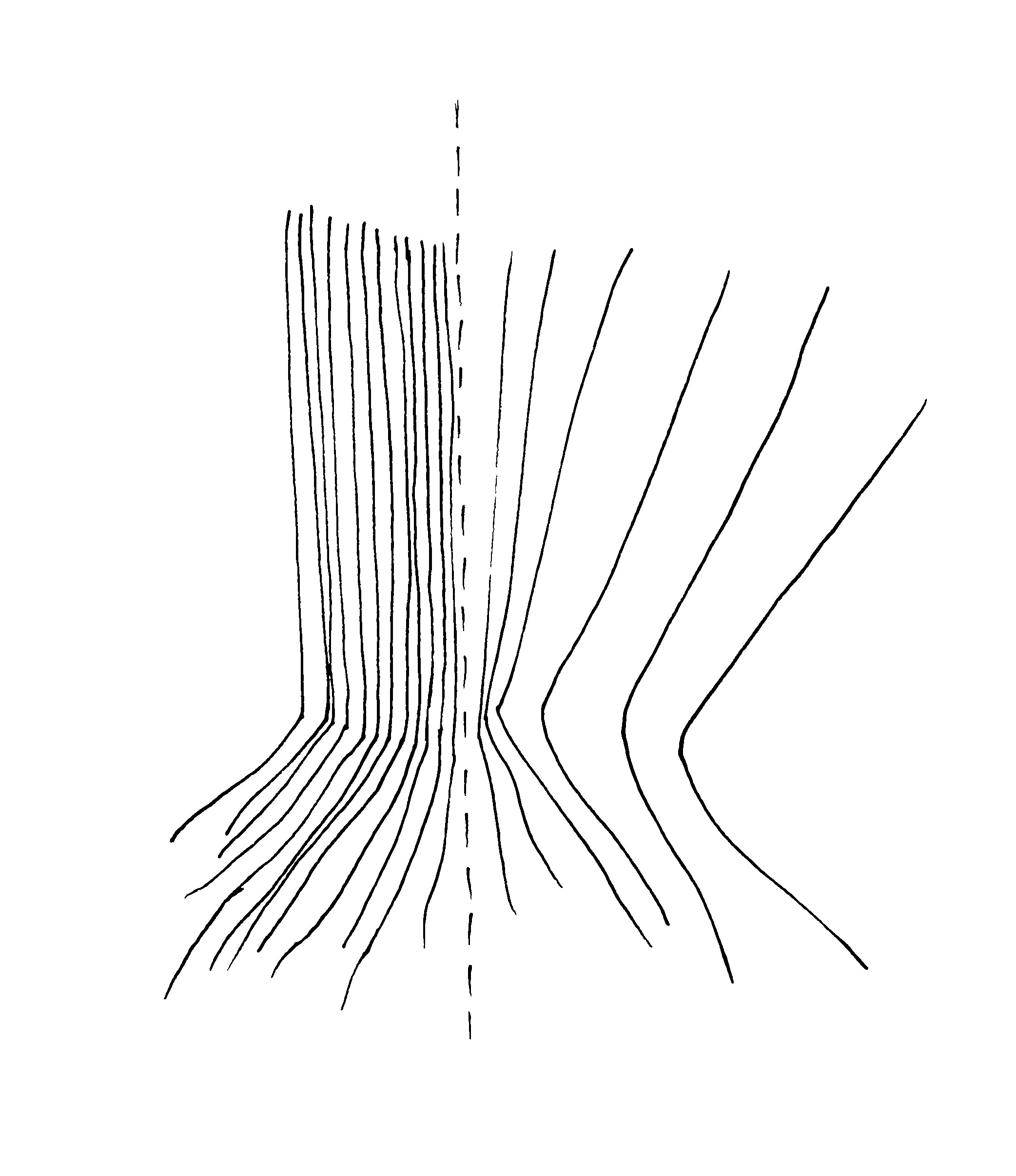

The natural sciences, like physics, have come a long way to finally find themselves at a crossroads created by another famous man – Albert Einstein. His equations pulled another veil off this simple arrangement of time – unity. For they showed us that time passes at a different rate in the valley than it does at the foot of the high mountains. If two people were separated at the same moment, one remaining in the valley and the other high up in the mountains, when they met at the end of their lives their clocks would show a different time. Time is thus fragmented into a kind of horizontal layers, into an infinite number of lines to which different lengths belong. By way of physics, we might pass on to more complicated considerations, in which my competence is already weakened. Let us therefore take the next detour, which is language.

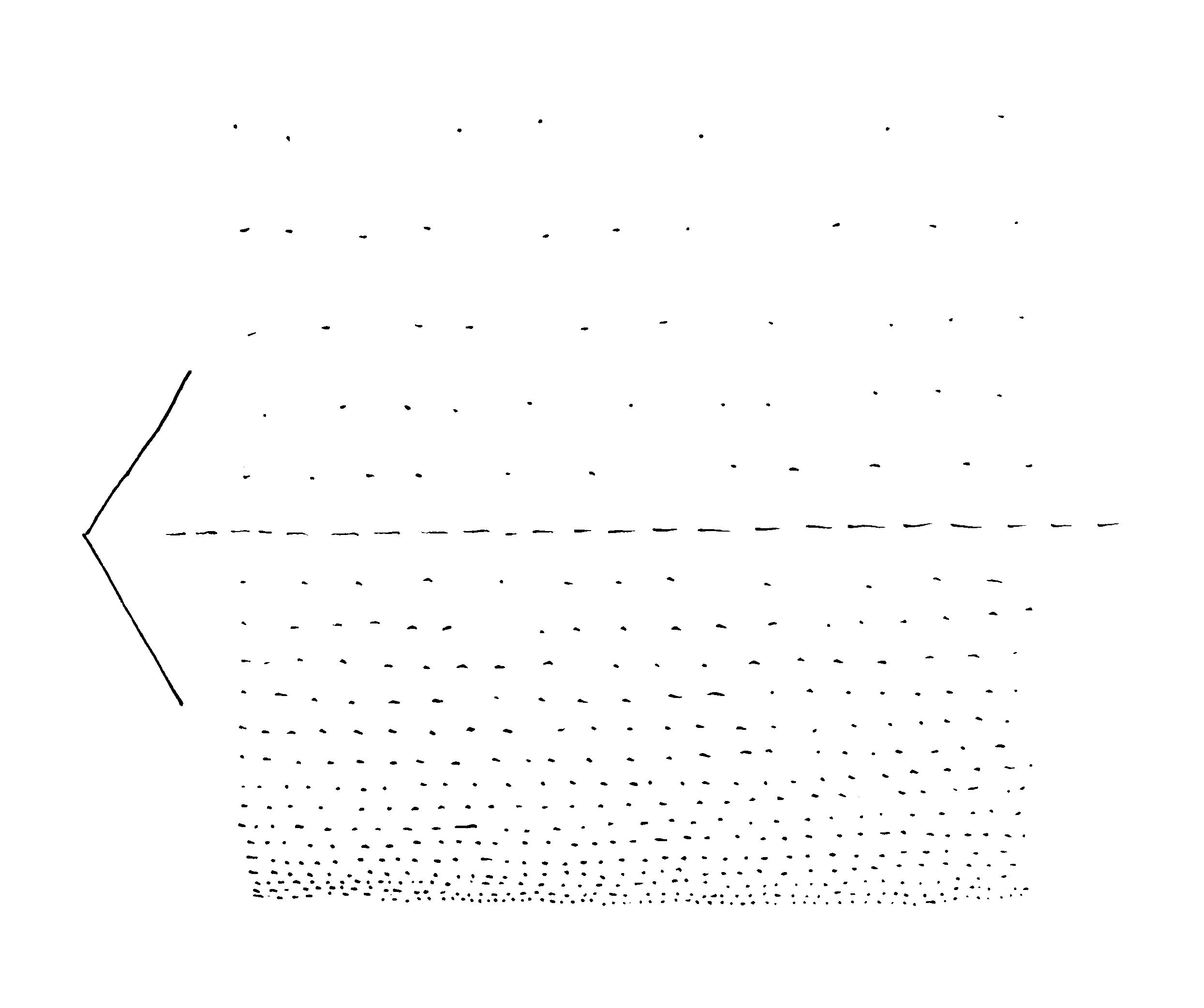

Time also “spills over” into language, the rules of which make it possible to name what has taken place, what will take place, and what has taken place up to this moment. The English language is richer in articulating the sequence of events than, for example, Slovak. Other languages, on the other hand, are narrower in naming sequences of events, but therefore more precise. Does this mean that there are also different tenses in the multitude of languages through which we communicate? If a time sequence described in one language cannot be translated into another, does that mean that it does not exist or that it is in an unknown abstract nebula beyond words?

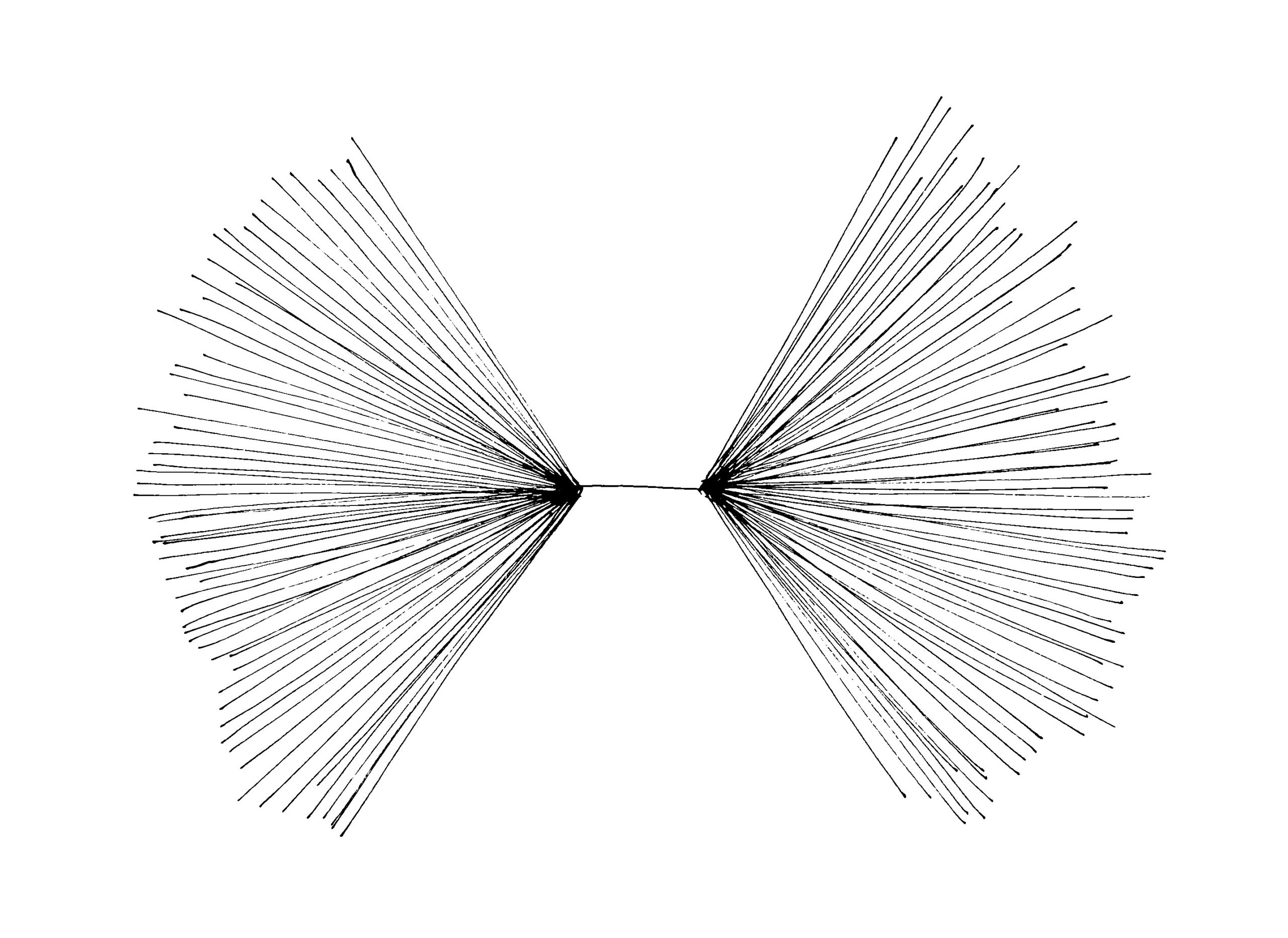

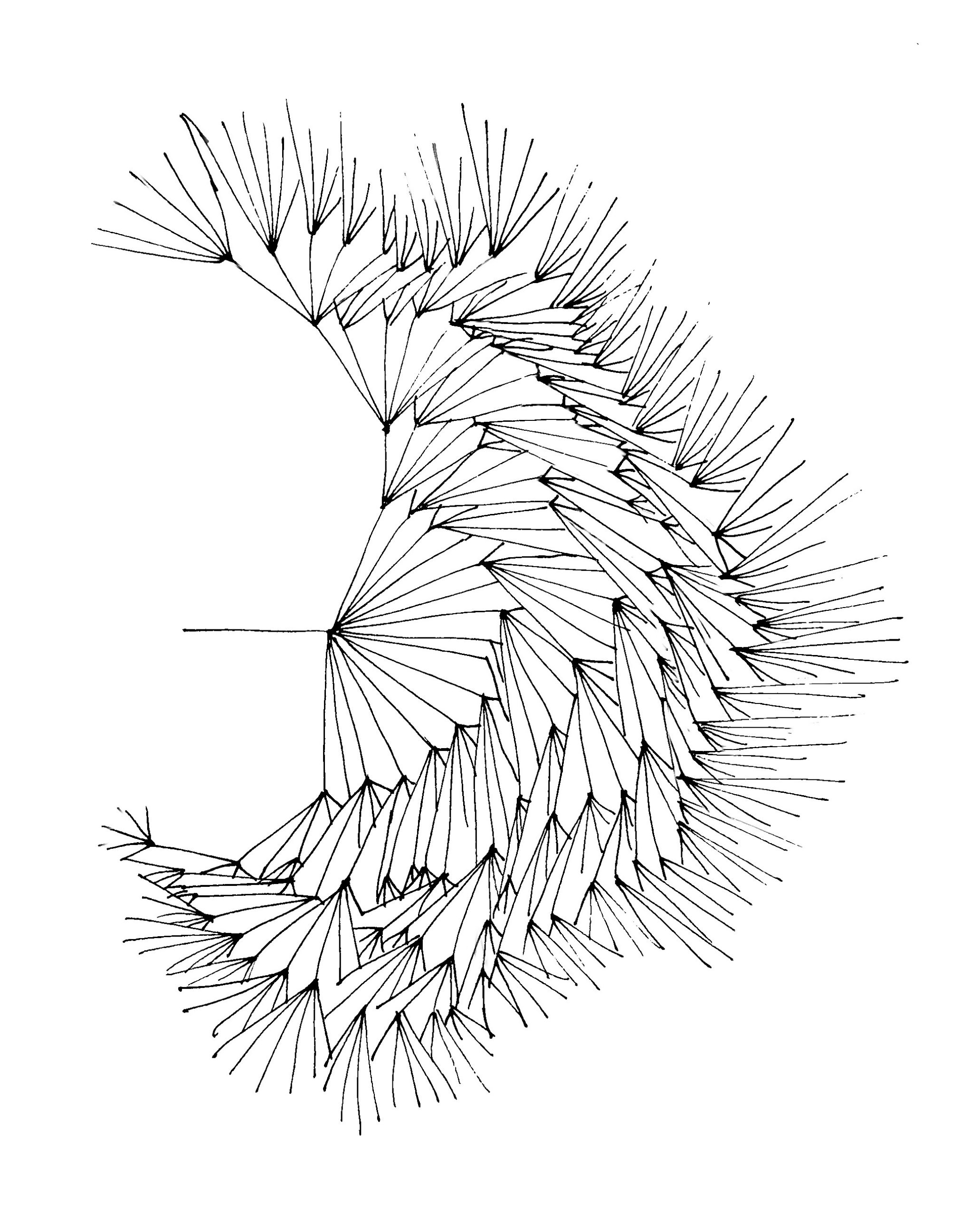

As we can see, even in the case of language, time, and with it reality, has fragmented into a set of grammatical sentences expressing different plot situations. Let us turn, however, to philosophy, which offers us innumerable parallel avenues for our question. I will choose just one – the path of Bergson and Deleuze. The main actors in their account of the nature of reality are words like transition, change, becoming, continuity. Reality is understood as a duration, as a certain current, a flow in which – as in Anaximander’s statement – things change. It is characterized by an inner happening, a dynamism. Reality is essentially manifest in movement, in the constant birth of something new. Deleuze, following Bergson, uses the word virtual to describe this nature of reality. In considering it, we must forget its connotation of being tied to digital technologies and concentrate on the scholastic meaning of the virtual, which suggests a kind of productivity, openness, potentiality, power, emergence. The dialectical double is the actual, that is, the finished, born, real, material or concrete. The actual is something that extends in this moment and that we can directly observe. But things are first present virtually, in an abstract stream of time in which they persist in a kind of readiness of becoming.

We can help ourselves with the work Untitled by Dana Tomečková. Her white cube was made with a loose material, powdered sugar. We thus recognize it as a cube whose edge is distorted on one of its sides and loses its precise shape. This work existed originally in an imaginary form, for example when Tomečková was contemplating an upcoming exhibition before going to bed. The very next morning she wrote it down and drew it in her notebook. Until that moment, the work existed virtually. It was about to become real, but it still had to wait for its opportunity – the exhibition situation. Yet it remained in a certain abstract nebula of Tomečka’s imagination, in which it waited for the precise contours and the concrete density of the powdered sugar particles that would predetermine its stability, and therefore its durability. The cube itself was eventually “materialized”, first as a test in Tomečková’s studio, then at an exhibition in Banská Štiavnica and later at another exhibition. And it is at this point of reflection that we are already moving in the plane of the actual. In the studio, the shape of the cube was the most perfect, as its floor was absolutely flat. In the same way, the sugar particles inside it were perfectly packed together and contained a minimum of air. At the exhibition in Banská Štiavnica, the floor was curved, and so the right side of the cube began to crumble more quickly. Ants smelled the sugar and gradually began to take sugar grains from the lower parts of the cube, which accelerated the cube’s disintegration. In another exhibition situation, the cube resisted the touch of the viewer until it changed into a rounded shape through repeated contact. As we can see, the individual cubes on display (actualities) differed, for example, in their degree of durability, the density of the sugar dust, the precision of the sides, the humidity of the air, and the interaction of the viewers, but their common denominator was a kind of strange “pre-existence” in the artist’s imagination (virtuality), in which it persists to this day.

The virtual and the actual thus represent the possible and the real. The number of updates of the virtual is unlimited. Even if this work exists in a museum in 300 years in the form of a manual, it will be able to be exhibited countless times, each time in a new constellation. Perhaps at that time its lifespan will be shortened due to the warming of the planet. Thus, actualization takes place through differentiation, in which facts (realities) diverge, change size or other properties. Reality, which is a duration, a constant emergence, is multiply fragmented into lineages. Things simply change.

Bergson and Deleuze approached the nature of reality with respect and found a “tailor-made” interpretation of it. They did not try to squeeze it into a preconceived structure, but retained its essential attribute – mutability.

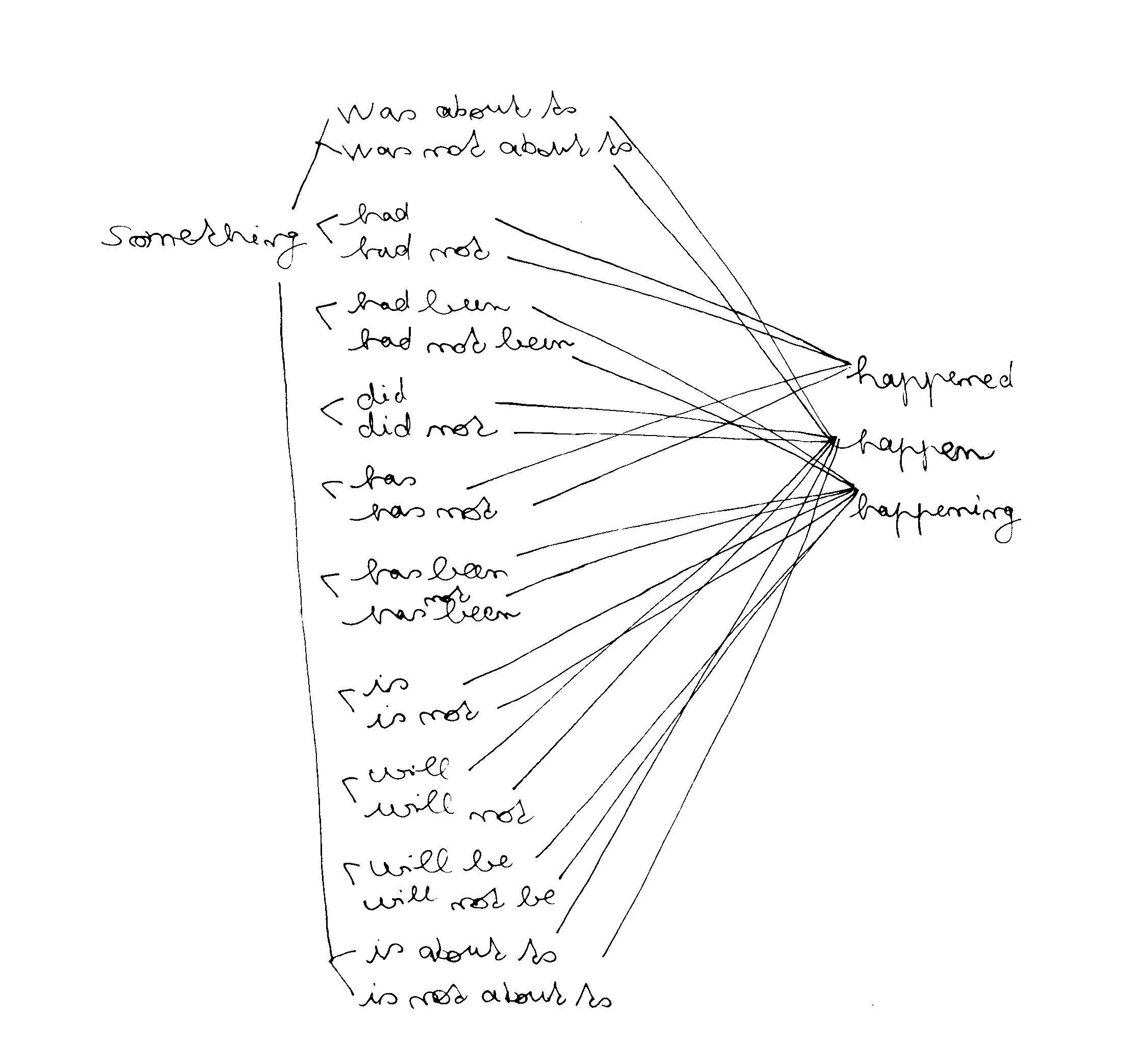

Variability is a long-standing thematic interest of Tomečková’s, who reveals it in slow but focused steps. In her thinking, the nature of reality and things takes on contours both in objects and in text or performances. The presented textual works Something Was About to Happen capture almost all the named attributes of duration – not violently, but sensitively, empathetically and intuitively. The work consists of a vast number of sentences that contain a temporal/ideal break. The latter fragments them into potential sequences – as if they were variations of cause and effect, creating intricate webs and also revealing the limits of language in articulating the temporal sequence of events. He lets us immerse ourselves in a density of probabilities and possibilities in which even nothing has its own self-conscious status – being. Negative notions such as nobody or nothing are abstract in her thinking – unrelated to reality. Tomečková has also “written” this very mutability into her objects, more precisely, into the process of artistic creation. Working with “bulkiness” gives them a fundamental quality – ephemerality. Her objects are born to disappear. The fragments of the human torso are different in each exhibition realization, they are destined to extinction, decay, entropy and to a new actualization. It is no coincidence that Tomečková’s works defy adjustment and that they are not easily absorbed by the market… It is the market that demands the opposite – durability, precise parameters within which the works will be measured and financially valued. Rigidity and precision simply do not do these works justice. And that’s a good thing.