Through the City / SENSITIVE EDUCATION IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING

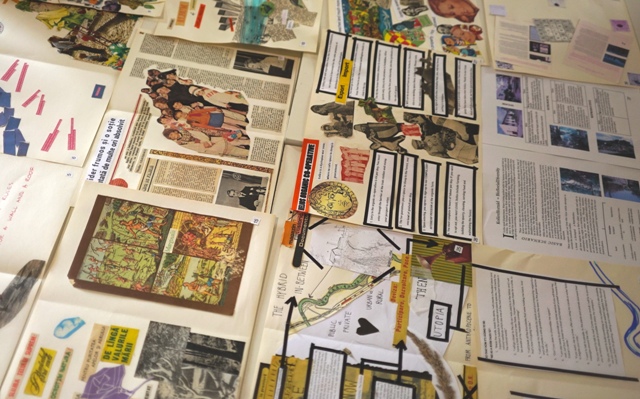

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

Urban design

For us, urban design combines architecture and urbanism, sociology, economics, geography, politics, law, artistic approaches and many others. We start from the conviction that the creation of space can be understood as any activity that consciously reshapes it. Urban design thus places importance on the processes that create space.

The expansion of what urban design means, as well as new forms of such making and learning about it, is not a new topic. It is also addressed in the current concept of the New European Bauhaus, which to a large extent influences the vision for local architecture.[1] It is also addressed abroad by Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider, Jeremy Till and Markus Miessen, for example. In their conception, urban designers are people moving at the intersection of different disciplines that deal with space – geography, architecture, sociology, politics, and many others. They thus also move within other frameworks of place-making, such as community engagement, planning ethics, policy design, research as spatial practice. In doing so, they also make use of the diverse tools of these disciplines. Many other authors have also charted related transformations of teaching in architecture[2].

However, in Slovakia and in the broader context of our region, there is little change in the formal and non-formal education system. At universities, placemaking is still taught exclusively in schools of architecture and urban planning. This learning tends to focus on the physical transformation of space and is often disconnected from other disciplines that focus on all of us – people, systems, animals, plants. The social and political dimensions of the practice are thus largely missed, and with it the extent to which our outcomes affect the daily lives of people and other living or non-living actors. Practices of making space (physical or otherwise) that are interdisciplinary, inclusive, progressive, egalitarian, socially and environmentally just are still not popular among the group of those who have the power to design the city. Indeed, the hierarchical structures of education in architecture and urbanism predetermine and reproduce a narrow delineation of disciplines. The current wave of protests by university lecturers in the neighbouring Czech Republic speaks volumes about the conditions in which teaching takes place, thanks to the severe underfunding of public education.[3] However, there is hope in the air.

In our region, approaches are beginning to emerge that can go beyond this stereotype. For example, in the neighbouring Czech Republic, the Academy of Fine Arts (where the architecture school is also located) is headed for the first time since its foundation in 1799 by a woman, the Bratislava-educated Mária Topoľčanská. Her agenda also focuses on the consideration of social issues such as affordable housing. But it also focuses on the ways in which we learn together. In Slovakia, the ways in which we learn together in urban design, and thus co-create the field, are the subject of our Never Never School. In this article we outline what such a process might look like.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

Why the caring pedagogy?

During school, we go beyond the teacher-student hierarchy and learn together about current challenges that we see as dependent on our caring for each other to solve.[5] For the opportunity to care, to create and develop relationships, and communities in our neighbourhoods, is at the heart of the caring city for us. And in the context of this, attentiveness to the needs of different actors and stakeholders also stands at the heart of caring. For each and every one of us has different visions and needs based on how we have been educated, our perspectives, experiences, or what our bodies allow us to do, for example. These needs are also reflected in ideas about the shape of the making of a good city, which is thus slightly different for each person – these differences and multiplicity put Never Never School in contrast to traditional education in the foreground.

Such an approach can be a way of strengthening the department’s capacity towards inclusion and social and environmental justice, and thus a chance to better confront socio-economic crises in terms of a vision of creating the conditions for a ‘good life'[6]. To zoom in, we outline the perspectives of caring pedagogy according to the individual members of the Never Never organizing team: Our colleague Susan, an architect, sees caring pedagogy as supporting people to learn what they and they alone are interested in, based on their needs, or linking needs with the perspective of their potential interest. The key word in such teaching is to guide. To direct what those people want to do, in different ways. Sometimes that means discussing with them for an hour and a half, other times it means drawing with them for 15 minutes, or putting them together with another group or individual… We put everyone’s teaching in the context of the needs of other people and things around them, including our own needs. As our sociologist colleague Lydia says, it’s also about helping them to acknowledge their current attunement, their previous experiences, their political views, the ways in which we work… and being able to express them based on that in their other work.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

According to Viktória, again an architect in Spolka, some form of emancipation is important in careful teaching. In Slovakia, everything in schools is defined within a hierarchy. In contrast, a more emancipated, democratic process of discussion can encourage learning. But the context where we learn is also important. In the case of Never Never School, we are creating a space for learning in a place that no one has previous experience of. The possibility to create a different and own space to learn, where there are no clear rules about what we mean by architecture, for example, is in itself emancipatory. Also according to architect Kristina, informal methods and personal experience provoke a more sensitive, deeper relationship to space, to civic engagement and connection to the story of the city around. The traditional hierarchical framework disappears and so everyone or every one gets a chance to express themselves in the most comfortable form.

However, creating a space where the rules are not clearly established is very challenging. The basis of ‘caring pedagogies’, according to our collaborator Hana, is giving freedom to the person who is learning, but also giving them the tools to manage this freedom, because we are not used to such freedom. In short: you have the freedom to do whatever you want, but we don’t just leave you to it. You can turn to us, count on us. An educator creates a safety net. She thinks of people’s individual needs without evaluating what they are. And that’s one of the hardest things about the caring form of teaching others that we talk about. For example, we also pay attention to the person who shows up and has little involvement in the discussion. We also adjust the room itself according to whether the learning is being attended by, for example, a person who cannot hear or see well, and so we have to adjust the size of our presentation. When the person involved is not caring, you should be able to detect this early on and start to work with it openly and patiently. Think about the detail.

Co-creation doesn’t just belong in after-school practice

All of this translates into our teaching. At Never Never School in 2018, the learning formats were blended. On one day we were learning to map a place by listening carefully to it, on the other we were recording the landscape through a movement workshop… These were formats that created alternative ways of expressing and discussing the topic. Discussing in verbal or written form were the most commonly used ways. However, people who are not naturally good and good at them are not given the space to engage in discussion. Having the opportunity to express my opinion and expertise in a different form was liberating and personally very beneficial. Information and experiences absorbed from a non-traditional method of teaching or observation stay in the memory longer and offer room for free analysis and interpretation.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

One manifestation of good caring teaching is that each and every one retains his or her ‘handwriting’ in the metaphorical sense, but deepens and develops it even further. In 2021, during the summer school, we practiced caring teaching through offering consultations for participants’ projects. Their results did not differ from their initial proposals. But they were deeper, more developed, and… really very different from one another. That was what pleased us the most.

Caring pedagogies are strongly linked to the practice of co-creation and the leadership of participatory projects: in them, we conceive a space where people can think with us or contribute in any way to the making of the city. Never Never are a test of methods of what can work and what can’t, where one feels comfortable and can think arbitrarily and where not, … and these are all different positions of involving people in the making of cities. Pedagogy and participation are linked and we often use the same methods for them. Both are about co-creation and not about one-way perception of information. But participation, facilitation, and urban design, like careful learning, all take time, time that costs us something. To prepare ourselves for them, to take something from them and put it into practice, to personalize our experiences and to be able to handle them in the long term.

‘School’ originally means leisure (from the Greek). It is the time we need to be free. It cannot be done without it. As Susan says, learning through the shared experience of caring pedagogy is the kind of learning that not only works well, since we learn by imitation from a young age, but that we continue to learn through our being and stories. We’re kind of going back to centuries past, but there’s nothing new to add to that.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.

Photo: Gréta Čandová, 2021.