Through the City / TREES ON THE CITY PLANS

Image generated by the Midjourney graphical model. Prompt by Michal Sládek.

Red and white tape is stretched across the sidewalk, you need to cross to the other side. Beyond the tape, branches can be seen on the sidewalk and a car with a work platform extended into the tree canopy can be seen on the road. The man on the platform is doing the trimming, a chainsaw can be heard cutting through the wood. I watch the act of caring for the trees in the city.

What are those trees? Are they okay? What are they called? The trees have been silent residents of the city since its inception. Few have appeared in it by accident; most of the trees in the city grow in predetermined places. They have often outlived the plans and their planners, and by their presence they act as an unchanging backdrop to urban life. As a pedestrian, I move at the level of the trunks, in which the trees meekly give way to the other creatures and objects of urban life. Their intricate roots cannot be seen through the sidewalk, and one has to raise one’s head to the canopy.

The tree, however, is extraordinary in the city. It harbours symbolic significance and always carries a political layer in the context of the city – the decision to place it. I wonder who might have planned to plant it on this street and how.

Calling for trees

Trees are enjoying a new interest in the city. A million trees for New York! A million trees for Prague, or a million trees for Freetown, Sierra Leone. In just two years! Among them, a modest 10,000 trees for Bratislava. A tree for its extraordinary abilities provides an ideal solution to a city’s complex problems. It shades against overheating, provides food for urban fauna, retains water and binds carbon dioxide. Thus CO2, a gas that has become the unit of measurement of climate impact. Thanks to satellite imagery and smart evaluation of big data, compensatory tree planting can be accurately calculated and targeted. (Tree planting is a popular method of carbon offsetting, whereby the amount of CO2 produced can be bought as an indulgence in the form of new trees.) A measure easier than changing people’s habits – after all, no one can object to tree planting. Cities (or rather their representatives) around the world are joining in and announcing major urban initiatives. At the same time, they are also responding to the new public interest in trees in the city, by making information available or naming them (the portal in the Old Town of Bratislava [1]).

Interest in trees is part of an increased interest in the biosphere around us. Based on biological and biochemical discoveries, more and more attention is being turned to the living aspects of flora, hitherto perceived in a static way. On the communication between plants, on the transmission of information through the understorey, on the richness of plant-animal interactions, even in urban environments. After animal rights, the ethics of plants, fungi and living organisms in general are beginning to be discussed [2]. Under the pressure of the climate crisis, this knowledge is being translated quite quickly into new approaches such as urban beekeeping or the creation of unmown green spaces.

How to draw a tree?

I slowly walk past other trees in the alley. I imagine the drawing on which they were planned. What did they look like? Like circles with a dot in the middle? Showing a tree in a drawing has its pitfalls. The first problem is technical: how to reconcile the complexity of a mature tree, which can have two hundred thousand individual leaves, with the abstract representation of a drawing. In the days of hand-drawn drawings, this problem also had a utilitarian dimension; rendering the complexity of the shape was time-consuming in practice. Therefore, in many drawings the tree is shown only as a circle, possibly supplemented by various hatching. The more detailed rendering of the full canopy in plan view introduces further problems. In a strictly orthographic representation, the crown obscures the layers beneath it, and does not give sufficient information about the height of the tree. Another challenge is the tension between the drawing of the structure, which has to be filled in accurately, and the growing nature of the tree, which grows into a shape that we cannot pinpoint. And is the exact species of tree actually supposed to be part of the architectural design, as is the composition of the wall? Or is that the domain of another profession?

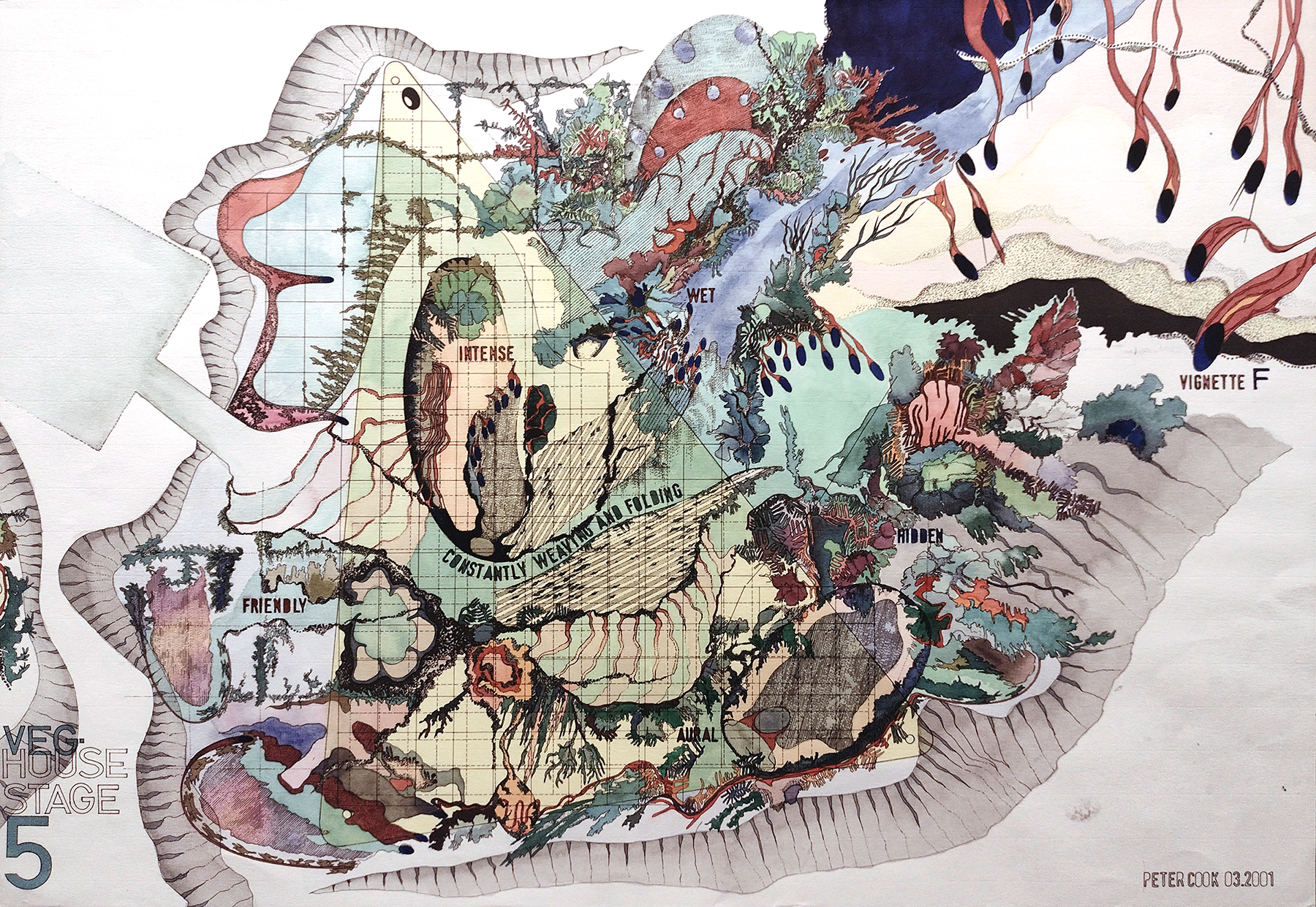

Last but not least, the political level permeates the drawings. As with mapping, the decision of what and how to depict in a drawing is a political act. It has the power to highlight or render invisible some aspects or some actors in the space. The drawing of a proposed state can also be understood as a mapping of an imaginary space in which the author or author depicts what he or she considers important. For communication with builders this tends to be the agreed language of the design documentation, but the drawing may look different. Peter Cook’s Veg-House drawings abstractly highlight very different aspects of vegetation. And without a legend, it is clear what the living and organic parts of the space are.

Peter Cook, Veghouse stage 5, reproduction from the exhibition at the Triennale of architecture Oslo, photo Michal Sládek.

Trees and plans of Bratislava

How does the theme of trees work with the design of new spaces in Bratislava? The design drawings for the current competitions are a good basis for current thinking about the future. How did the competition teams approach the design of new trees, and how did they deal with their imagery? What intentional and unintentional messages can be gleaned from them? What types of imagery are now being used? In addition to floor plans and sections, visualizations are also telling.

If an abstract representation is not chosen, the tree often appears in an idealized form. In adulthood, with a perfect crown shape and always with leaves. Contemporary computer work also has its influence; architects can reach for a ready-made, perfect predefined tree that can be repeated in the model. It is easier to use one model for all trees than to simulate their diversity. For example, as in the Urban Park proposal (U/U Studio, 2021). This way the trees have the same height, shape and colour. Although they are rendered perfectly, they look mechanical and thus affect the overall appearance of the drawing… Trees are not only shown in their cycle at the level of the year, where they alternate between flower, leaf, fruit and bare branch, but also in their life cycle. Trees in youth and old age need different protection and support, and look and feel different at different stages of their lives.

Project Urban Park Tbiliská Bratislava, U/U studio, source www.uustudio.cz

A tree has a specific value in the city, which can be accurately quantified and capitalized as the social value of trees[3]. It is the price at which its felling can be redeemed, or how much we would lose as a society if something were to happen to the tree. At a time of heightened interest, the real estate market has also taken notice of the economic value of trees. Idealized images of promised trees can attract clients. Thus, some project visualizations do not attempt to depict future realities, they fall to the level of advertising where the aesthetics of exaggeration and cliché are accepted. The sun’s rays shine through the slender green crowns of beautiful trees, under which healthy and beautiful people play and rest. However, this aesthetic also permeates public projects, such as the visualisation in the competition for Jurigovo námestie by 2M architecture studio. In this context, such a depiction looks almost untrustworthy.

Project for the competition Jurigovo námestie – 1st place: 2M ateliér architektúry, source: www.mib.sk

However, there are projects where we see a sincere interest in the drawings to show the intended diverse greenery. The project for the competition for the revitalization of Námestie Republiky (Amulet + sustektecl + Veronika Brabcová, 2021) is definitely one where the detail of the green design is surprising. Each specimen is identified by number and the drawings are accompanied by a tree legend. Existing and proposed stands are interspersed. The visualisations are not afraid to show trees, presumably a collage, of various irregular shapes. This suggests that various professions were probably present in the creative team enriching the design.

Project for the competition for the revitalization of Námestie Republiky – 2nd place: Amulet + sustektecl + Veronika Brabcová, source: www.mib.sk

The arm of the work platform drops down to a pile of trimmed branches. I hope the tree is okay and will grow here for a long time. I continue my journey through the town. I notice the many trees around me and reflect on the amount of care that needs to be given to them and on all that they bring to us. Their representation on architectural designs varies, but always can only come close to the complexity of the life of trees. The images generated by artificial intelligence (Fig.1) will bring the technical possibility to plant trees – individuals in different life and cyclical periods – into the visualizations. This will make it all the more necessary to think about the abstract part of the drawings. How could we depict the impact of trees on their surroundings, their relationships with other living beings and above all how to capture their needs. How not to forget the roots, the water, the pollen and fruits, the insects and birds and the whole ecosystem? Representing their needs would help to make them visible as important inhabitants of the city who should have a voice in its future planning.

Michal Sládek

Collaboration Viktória Mravčáková and Kristina Roman