Close Things / KVET NGUYEN

About a postcard whose edges we will never see beyond.

Found photographs are a special category of close things. They are anonymous moments in time that we stumble upon by chance and speak to us in some way. A found photo represents a brief moment in the life of someone whose life reality – before and after the shot was taken – we will never know.

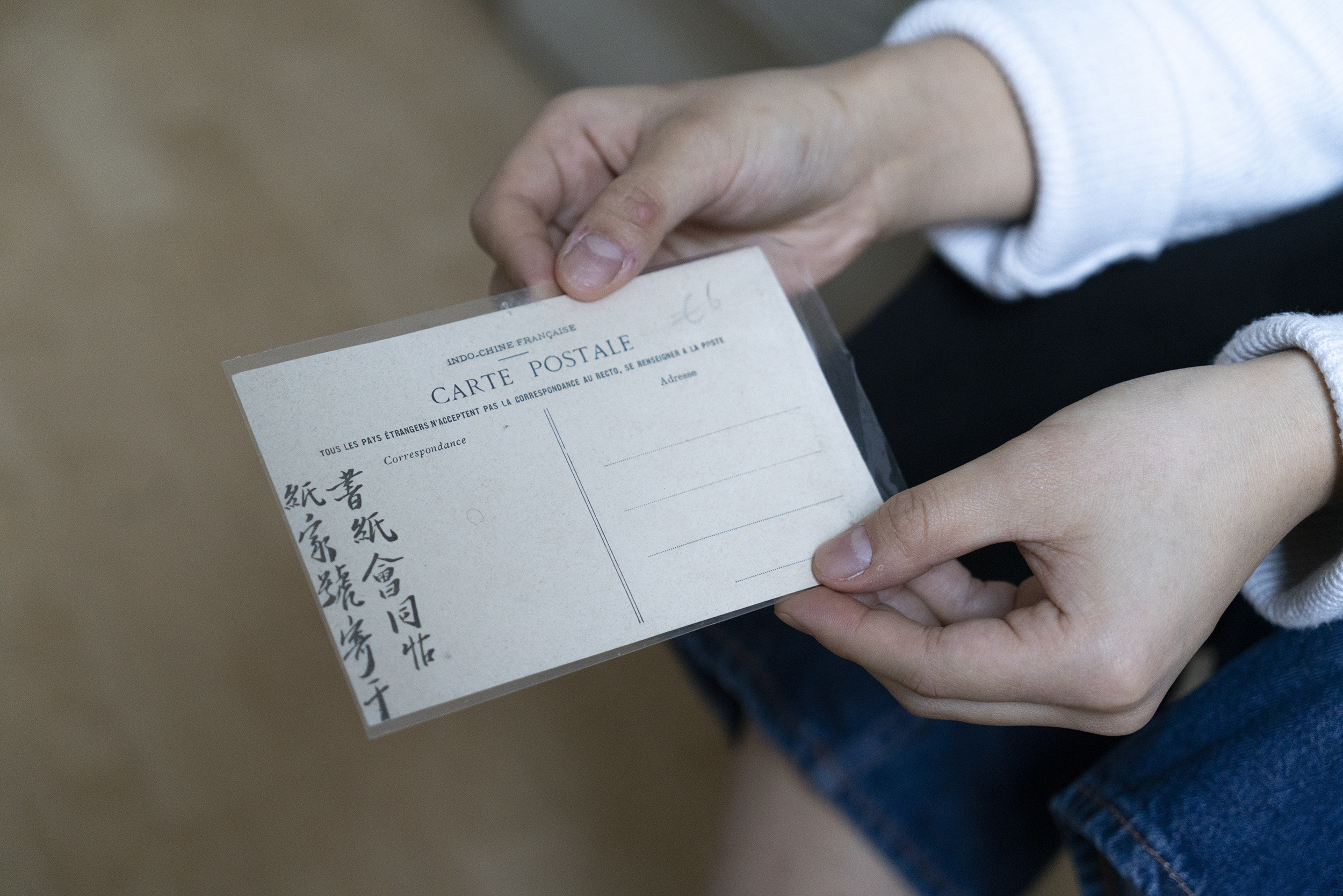

If we could peer into the moment when the photograph Kvet has chosen was taken, what would we see beyond its edges? In this case, too, only a slice of the (staged?) reality of what was once French Indochina remained, a shot that traveled through three countries to end up in the hands of another photographer, provoking her with questions.

Have you ever collected anything? Or else: is there a tradition of collecting in your family?

I usually start and stop collecting, I can’t be systematic about it. But my parents collect everything (laughs). Especially now that they’re older, they need to surround themselves with things, like surround themselves with security. And they really collect everything: clothes, necessities of life, plants, food…

When I think about what I have the most of…it’s scrapbooks of papers, texts, notes, various sketches, photos that I think I’ll get my hands on someday, that I’ll process in some way. Gradually they accumulate, and then I don’t know what to do with them.

So it’s pronouncedly stuff related to your work.

Yeah.

And how did this close-distant object come to you?

I was working on my Reframing Possibilities series and this postcard was one of the photos I analysed in it. It came to me about six months before I started consciously searching for archival photographs from the colonial period. I found it in the Netherlands, in a flea market in Hague, where I was living at the time. At the time I just thought – wow, cool, a postcard from Indochina, but I was completely unaware of the historical context, i.e. that Indochina was a French colony and all that behind it. I liked the visuals of it. And it was only gradually that the whole complexity of what the postcard meant came to me.

What exactly was your Reframing Possibilities project about?

The project had two parts. In the first one, I analyzed archival photographs. This initial part was never officially presented and was more of an experiment with found material. But I remember it fondly, as it was created during the pandemic and that was when I had the opportunity to really dig into the work. Exceptionally, I was not disturbed by any other activities. I wish I could do that again.

The archival photos from Vietnam (or former Indochina) that I discovered hit me quite hard. It’s as if that Barthes “arrow” that Barthes keeps mentioning in terms of how a photograph can strike a person has entered me. And I really started to cry over those photos, as death was present in some of them. It connected me to the history of the Vietnamese. It was a strange feeling. Even though I didn’t really know the country – I’d been there about four times so far – I felt a connection, something was still alive in me, and that’s what I wanted to analyse further. I opened an archive that I discovered on the Internet, through a gentleman who had been collecting photographs of Vietnam in large numbers – from the beginning of photography to the present day. In this archive, I found the most difficult images for me and printed them out. And then I wanted to “correct” that history through these photos, by physically manipulating them. That was the first part of the project. In the second part, I made self-portraits in which I was mirroring what I was feeling.

How exactly did you “fix” these shots?

For example, there was a photograph of women who were depicted naked, but in such a way that they were seen as objects, not subjects. I twisted the paper so that their bodies were not visible. Elsewhere, I cut out, taped over, folded the paper. It was such an experimental game, I enjoyed it also because I exceptionally didn’t take pictures, but worked directly with my hands.

Let’s talk about that particular photo – the postcard you’re holding in your hands. What exactly attracted you to its visual appearance?

It’s a black-and-white analogue photograph, and it shows women who were living in Indochina, which is Vietnam at that time. I thought it was strange that I only found it in the Netherlands. I was intrigued by the object they are holding, which resembles a twig – it is an opium pipe. But I didn’t find out what it was until later. I can’t even describe it, but it’s so strange that I came across it in a completely unfamiliar place; I would have rather expected to find it in France. I imagine that she travelled from Vietnam to France, and from there she travelled through various paths to Hague, to the gentleman who sold the photos. And finally I found myself there, and I was impressed by her strange, attracting energy.

What struck me about it is that it depicts women spending time together in some kind of ritual, and it is the arc of the pipe that connects them. I imagine that there is some sort of conversation going on in the background.

Yes, what’s interesting about it is that I chose that postcard based on that nice, romantic visual. But realistically, there’s a dark side to it. That shot has controversy in it.

Metaphorically, one could talk about the other, or the flip side of the postcard. What do you think is hidden in the background of this scene?

These postcards basically served as a kind of mass propaganda for the French presence in Indochina and how life was lived there, showing some kind of superiority to the Indochinese people. The postcard was, in a sense, a power tool.

Like other postcards that depict cultures far from Europe (but colonized by Europeans), this is essentially just some small slice of reality that exoticizes the locals…

Yes, we’re still talking about photography. I’m wondering if the women were actually using opium, or if it’s more of a scene created for a photograph. Because at that time women didn’t have any high status in the society and opium was more used by men. At the same time, one of them seems to be the more inferior one, probably a maid, and the other one holding the branch is either a housewife or a woman in some higher position.

Now that you say that, I sense that as well. There’s a certain dynamic or hierarchy present there. Despite the fact that they are equally dressed.

I saw another postcard similar to this where there was a man taking opium and he had a naked woman next to him in a strange position. That shot evoked different emotions in me, I can’t even describe them. I have no idea what the actual reality of those photographs was. I guess I would like to know.

In those times, the sources of information through which one could get to know the world were limited, and that is why even an ordinary postcard had a certain power, because it displayed, offered a part of some distant reality. And this is how it shaped the knowledge of the world…

Exactly, these images had a manipulative character, they offered a vision of the world that was limited to those who ruled, namely here the French colonialists. The photographs were thus deliberately used to their advantage. It was very widespread, and now there is a growing literature in the field of postcolonial studies that talks about how the exotic was perceived, how exoticism was manifested. It was really about showing through these images: look at how different they are. And often it was meant negatively.

Kvet Nguyen (Hoa Nguyen Thi) – was born in 1995. She studied photography at the Bachelor and Master level at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava. In 2021, she won the Tatra Banka Foundation’s award in the Young Creator category. Kvet Nguyen is actively engaged in the topics of otherness and identity not only in her artistic projects, but also tries to talk openly about it and open a discussion within interviews or other platforms.