Close Things / TOMÁŠ JANYPKA

Dylan's Sorrow and Nina Simone's Bubblegum

The emotions with which we associate a particular music are further enhanced by the enigmatic object of the LP record. Especially one that has already had some life behind it. Tomáš Janypka talks about Bob Dylan discovered in the north of Europe and the book Nina Simone’s Gum: A Memoir of Things Lost and Found.

(Tomáš pulls a close object out of a canvas bag)

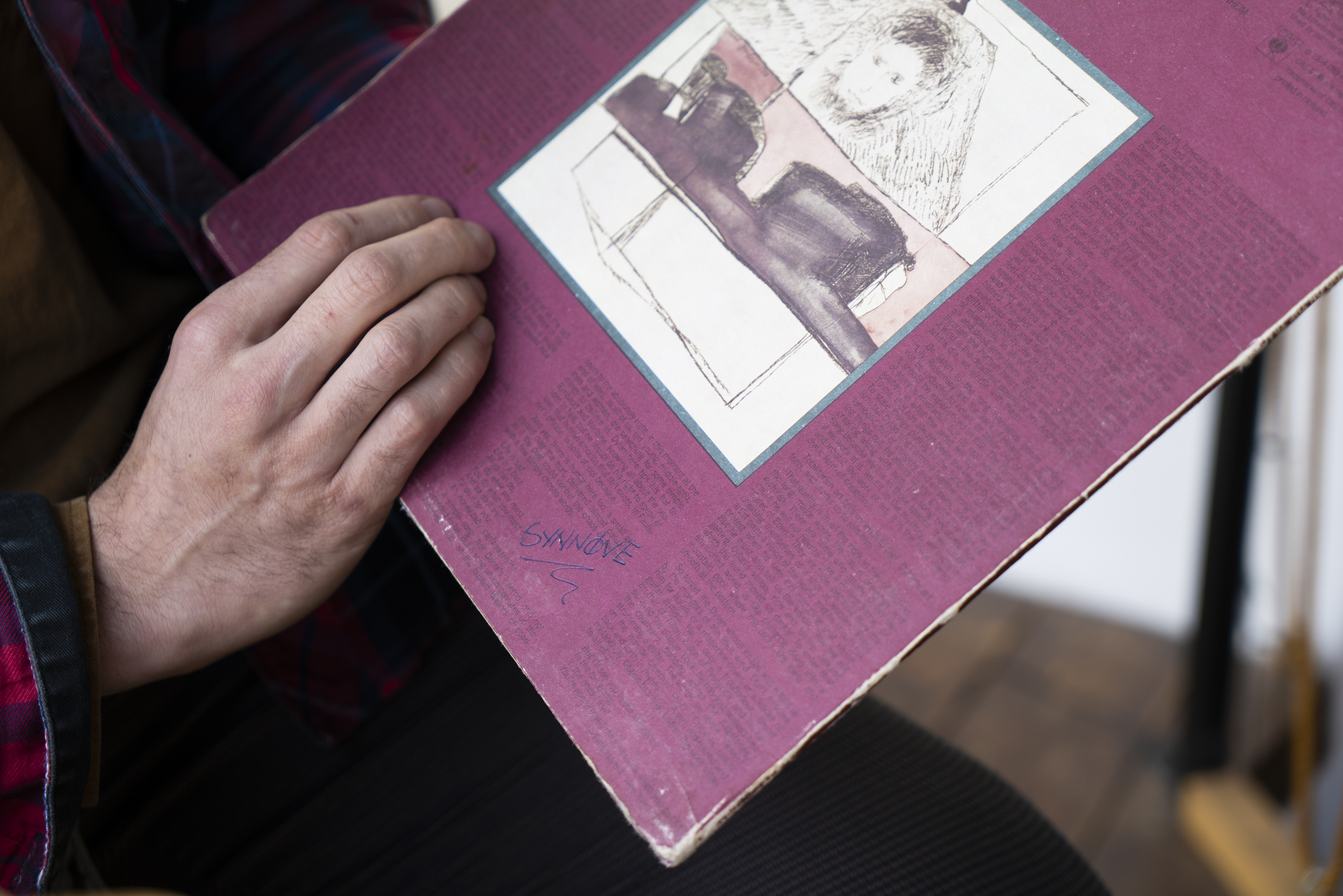

So it’s a record!

Yes, it’s a record. When you wrote to me to see if we could do an interview, I was just spending the holidays at my parents’ house and wondering what kind of close things I actually have there… And this was the first one that “called” me. Bob Dylan’s album Blood on the Tracks, along with his cover of it, is a very important object to me, emotionally as well. I associate different things with it.

I discovered the record when I first found myself abroad for an extended period of time – specifically in Oslo. I spent half a year there at Erasmus. I found this album at some flea market, where it literally drew me to it. It was a very important time for me, and coming back to that record now, it’s like it’s opening up to me again. Like Bob Dylan and meeting his music.

This album is made up of such “post-breakup” songs, they have a different vibe than the music of his famous 60s. After that big boom suddenly came songs that already had something different in them. I think that’s when he split up with his wife.

Every time I listen to a record after a long time, I feel that those songs have a power that they speak with. Dylan is a great poet to me, and I love his stuff, but this album, the whole album as it is, even with his cover, speaks to me so clearly somehow.

Do you go back to it often?

I have periods when I play it. But it has a specific vibe that gets me in a certain state. And I don’t always want to go there. It’s such an emotionally “stirred up” thing.

There’s one passage on the cover that I like. It’s part of an essay that Pete Hamill wrote in 1974:

Or listen to the long narrative poem called “Lily, Rosemary And The Jack of Hearts.” It should not be reduced to notes, or taken out of context; it should be experienced in full. The compression of story is masterful, but its real wonder is in the spaces, in what the artist left out of his painting. To me, that has always been the key to Dylan’s art. To state things plainly is the function of journalism; but Dylan sings a more fugitive song: allusive, symbolic, full of imagery and ellipses, and by leaving things out, he allows us the grand privilege of creating along with him. His song becomes our song because we live in those spaces. If we listen, if we work at it, we fill up the mystery, we expand and inhabit the work of art. It is the most democratic form of creation.

Totalitarian art tells us what to feel. Dylan’s art feels, and invites us to join him.

That’s very nice indeed.

I actually only got to this essay on the back of the record now that I’ve decided that my close thing is going to be this album. And this passage particularly resonated with me. It also connects to my own work, thinking about the space you offer in your work or in a particular piece to yourself and to the viewer. About the amount of space you open up that the viewer themselves can fill, evaluate, and bring their own activity into.

What kind of things do you like to surround yourself with? Are there any types of objects you like in your environment?

Definitely notebooks. Different kinds of notebooks. And books. As far as domestic space, I like a certain cleanliness of living, but I also like different things that one finds or gets from someone. For example, a postcard. And somewhere I have a football card from my uncle that he had printed and enjoyed (laughs). In our family home, I have a tree made of coral that has been hanging in my room forever.

Things close to me are also close people or situations that I perceive behind them. By being around, they can sometimes speak. Often, just when I need it, I can relate to them.

I’m not sure I’m any great collector, though.

Have you ever collected anything?

I remember now that I collected stamps. And hockey cards. But I guess that’s a different kind of thing. At a certain time I read a lot of fantasy and science fiction magazines, and at that time there was a Slovak fanzine called Fantázia. I remember at some point I subscribed to all the older back. But I never read them, I just had to have them (laughs).

But maybe I do have something after all. I collect tickets from theatre shows or concerts, and I collected travel tickets for a long time. Then I’ve always dealt with that purge that one does once in a while when you accumulate a lot of these things in your backpack. And in doing that, I always got to thinking about some kind of consistency in that kind of collecting. That evaluation of what not to do, what to do, whether I should put down every single ticket, or whether the one between Púchov and Žilina is not so important (laughs). These are such absurd collecting dilemmas. But I also like the purging phase that comes when I need to get rid of things. I’m learning to do that. The act of sorting is very important to me. But I still have a whole packet of this type of stuff, and I always tell myself when I’m looking at it that it can still serve a purpose. And then I say to myself, what would it mean not to have all this stuff, to let it go completely. At the same time, I’m not very consistent in my collecting. I do it because I need to do it, but part of me wonders why actually. It’s such a constant internal dialogue.

The way I think of it is that it’s information about me preserved in some kind of matter, it’s captured time, and it’s actually captured what I was. These fragments can recall some part of me: they remind me that this is also how I felt, this is what I dreamed about, thought about, feared. Something in this feels very important to me. One was somebody when one was seventeen, and it’s impossible to go back to that feeling – to what we all were at that moment. Unless one records an album, like Dylan, for example, that kind of connection is not possible. Perhaps collecting is such a reflex, an attempt to at least have something material when one hasn’t transformed anything into a personal statement.

I was also thinking about how it relates to what we’re living in, that nowadays everything can be captured on a cell phone or recorded. But that’s already connected to a book I have that’s also related to this conversation we’re having. It’s about objects – things that are close to us, and at the same time about the inspiration related to what they hold. In the sense that their presence, their relationship to them, can bring other, new things.

What kind of book is this? Do you want to show it to me?

I can.

Nina Simone’s gum. Good title.

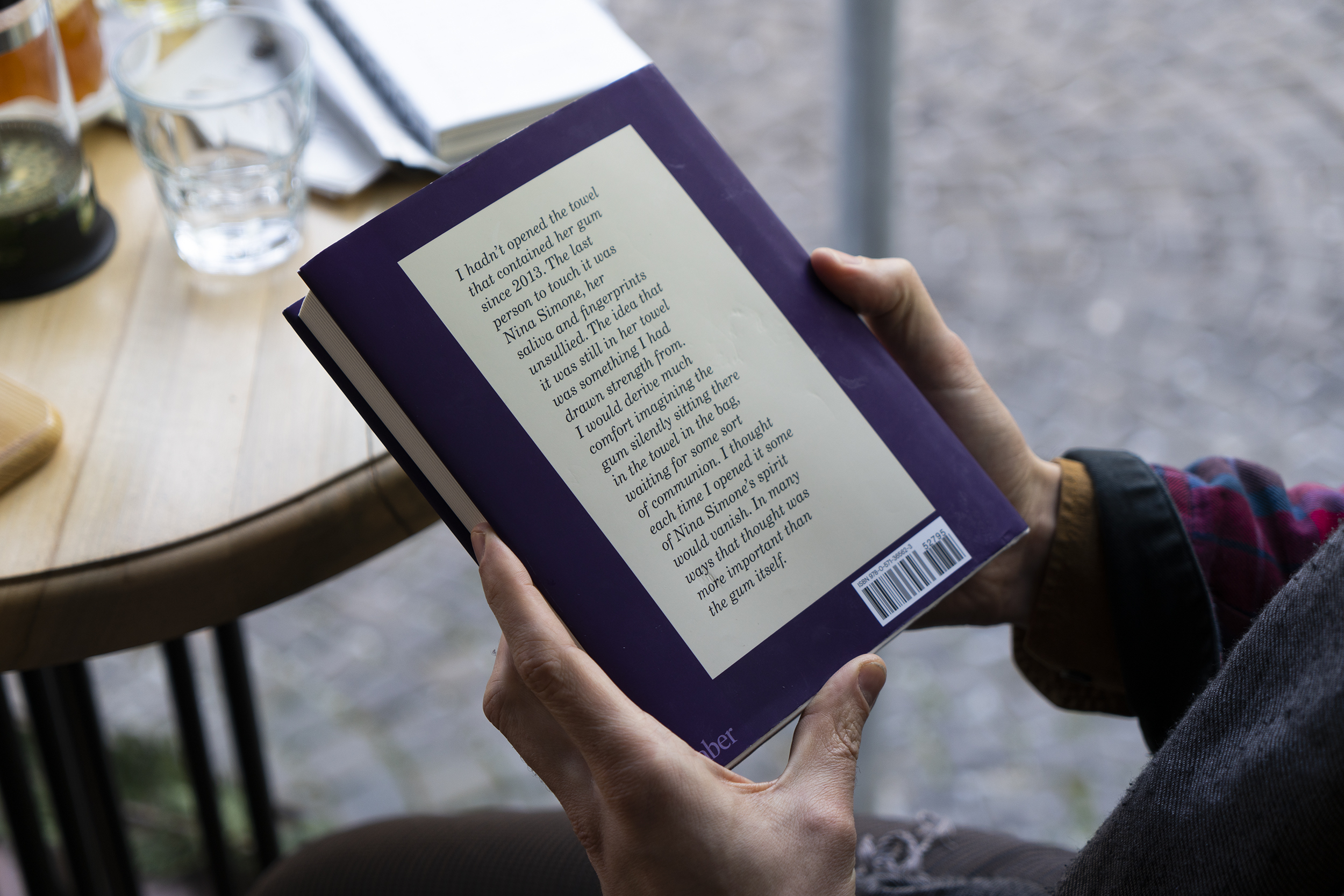

I will try to say something about it briefly. It’s called NINA SIMONE’S GUM and it’s written by Warren Ellis, Nick Cave’s musician.

It starts off by saying that in 1999, one of Nina Simone’s last concerts was in London, and Warren Ellis was there. Nina Simone was getting on in years and when she came on stage it was obvious that she was finding it difficult, that she wasn’t feeling well. When she walked up to the piano, she pulled gum out of her mouth and stuck it on. And then she started to play. In the course of that playing, something changed, as if some great transformation had taken place. At least that’s how people who experienced the concert, including Ellis, describe it – that it was one of those great transformative experiences. The music, the communal act of that concert changed something, something happened there, and they witnessed it.

When Nina Simone finished playing, Warren Ellis ran onstage, quite spontaneously, took that piece of gum from her piano and wrapped it in her towel. At that point, no one knew about it. He then carried it around with him for the next 20 years, like some kind of talisman. First on tour, then he had it stored in some place, he describes the whole process in the book.

There was a documentary about Nick Cave called 20,000 Days on Earth that came out in 2015, and I think that’s where Ellis first mentioned this thing. Until then it was just his, such a very important artifact tied to his inspiration, basically like a time capsule of Nina Simone with her spittle-stained, gum-stained teeth. And it was at this point, in conversation with Cave, that he began to share this precious thing of his with the world.

Finally, Nina Simone’s gum was on display at Nick Cave’s exhibition in Copenhagen last year.

Did they exhibit that original gum, along with her towel?

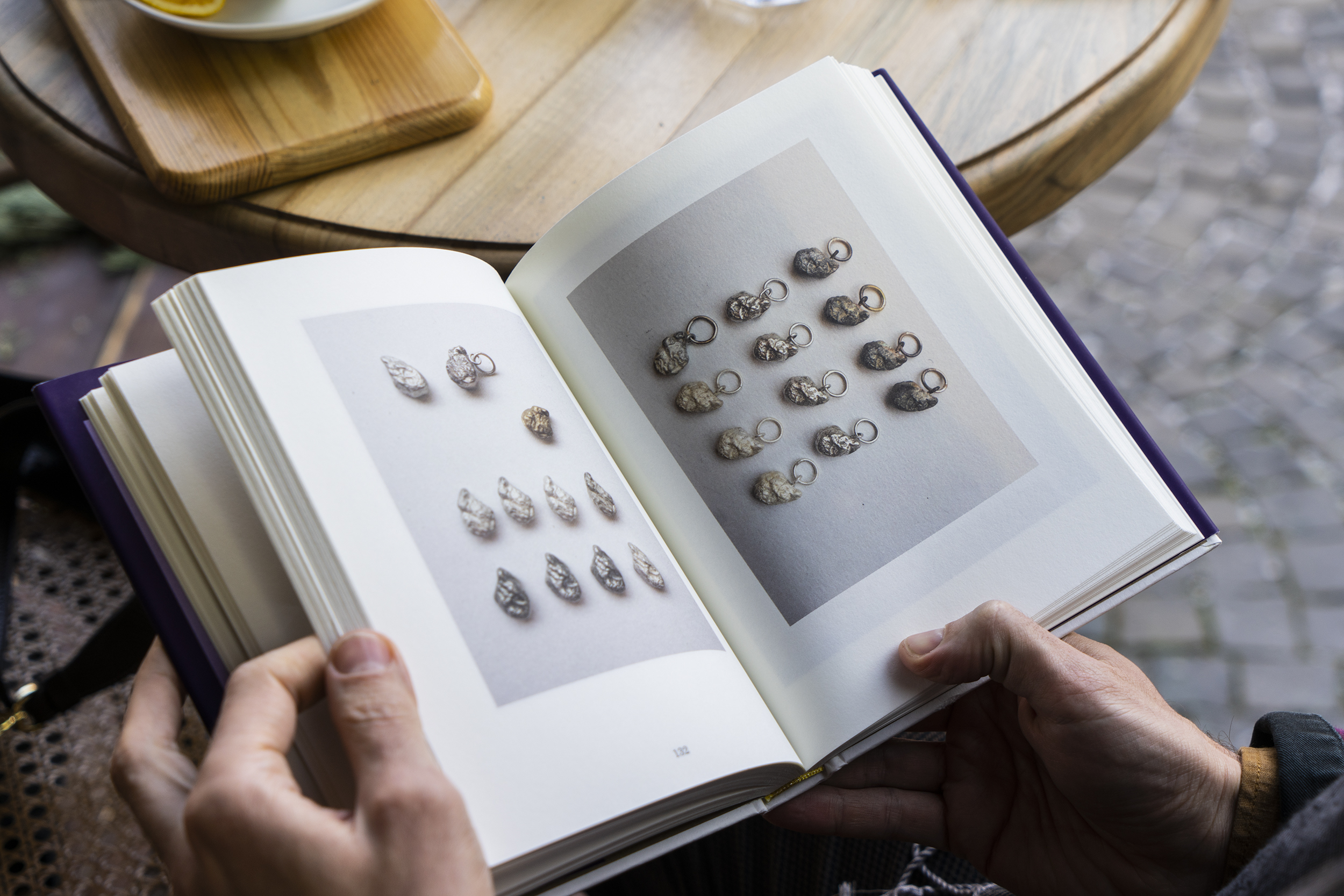

Warren Ellis decided to make a copy before that. In the book he describes the whole process, how he found a jeweller he trusted, how they then worked together – the way he describes this process of transforming the object is a very interesting part. It’s clear from the way he talks about the relationship that he has with the gum that this is a very important thing for him. Just the very beginning of it – when he climbed on stage to get it and didn’t think about it at all, he just had to do it.

I get the feeling from that that it wasn’t just about taking away a memory from the gig, but there was another force present.

The energy of that particular moment captured in the object.

Yes, and the care he took with it is also remarkable. In the book, he recalls the moment he and the jeweler first opened the gum wrapped in a towel. She also contributed a letter to the book describing that moment. Although it all sounds rather bizarre, she said it made a strong impression on her as well. And that’s why this story fits so well with the concept of close things for me. But this is such a transcendent object, such a modern relic.

Chewing gum may be the central point of the book, but Ellis writes about other objects in the book as well, opening up a kind of thinking about things there, describing very nicely just our relating to them. So overall he talks about these processes, about inspiration. It’s in some ways a good metaphor for art – how you can create from almost nothing, or how much can grow out of some ordinary thing.

Here’s one very good passage from the book:

The things we collect are the things that are of significance to us first and foremost. Outside your orbit and people connected to it they have no significance. They’re specific things. These things that are precious to us are really just precious to us. For some reason I have a hard time throwing out shoes that have served me well. I had a cupboard full of worn shoes in the corridor, and eventually I started photographing each pair to allow myself to get rid of them. There’s a connection there. I can’t just let them go. Shoes I have used only for concerts, shoes that you can’t repair any more, shoes that have been repaired one too many times. I threw out the shoes. A few years later I lost the photos.

Tomáš Janypka (*1989) is a creator, choreographer and performer who primarily works in the Czech-Slovak context. He graduated from the Studio of Physical Theatre at JAMU in Brno. His main strength is his subtlety, openness and ability to collaborate with artists from different fields. He deals with issues related to our intimate events, the perception of the body and its limits, the weight of things on the physical and spiritual level. He considers how these experiences can be shared physically and emotionally in a shared space with the viewer. He is fascinated by authentic and personal moments in public space, which he captures through photography and text.

In 2020 he created together with Sabina Bočková the authorial work song lines: expedition 97/18, opening the theme of absence-loss of a close person. With Roberta Štěpánková, he has been organizing IMMEDIATUS – a series of instant nights since 2018. For Festival Kiosk he co-created the immersive group Guides from 2018-2020. In 2021 he led a year-long research in the architectural and visual project Completing the Sphere by Juraj Gábor. His work has gone on to be featured in festivals including 4+4 dny v pohybu, Malá Inventúra, Hybaj Ho,…

As a performer and co-author, he has worked with Jaro Viňarský, Sonja Pregrad, Dominique Boivin, Petra Tejnorová, among others. He works as a feedback mentor and artistic consultant at DAMU in the international program MA DOT. Under the guidance of Berrak Yedek, he is becoming a facilitator of Somatic Dialogue. He is the co-founder of Z druhé strany, which represents the work of the emerging generation of artists in the field of contemporary dance and live performing arts.