UnArchived

Skopje, Total Plan

Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, was part of the former Yugoslavia during socialism. The author of the new city plan, which laid the foundations of the modern city, is the renowned Japanese architect Kenzo Tange. The progressive brutalist architecture of Skopje built during the communist period was subsequently replaced by the folkloric style of the new national program.

The starting point for the rebuilding of the city was the 1963 earthquake that destroyed the city (2,000 people died and 65% of the buildings collapsed). The reconstruction project was both supported and initiated by the United Nations and was partly carried out by local architects. Kenzo Tange’s project for an area of about 2 km2 came out as the winner of an architectural competition. Other architects from Tange’s office included Sadao Watanabe and Yoshio Taniguchi. It was completed in 1980. Tange’s project was only partially built, but several iconic buildings were still created. Among the realizations is a building by the Macedonian architect Janko Konstantinov, trained by Alvar Aalto. The building was implemented as a state interest and was not well received by the public. That is also why it was publicly condemned after 1989 and the state apparatus decided to return to the period of Alexander the Great when redefining Skopje.

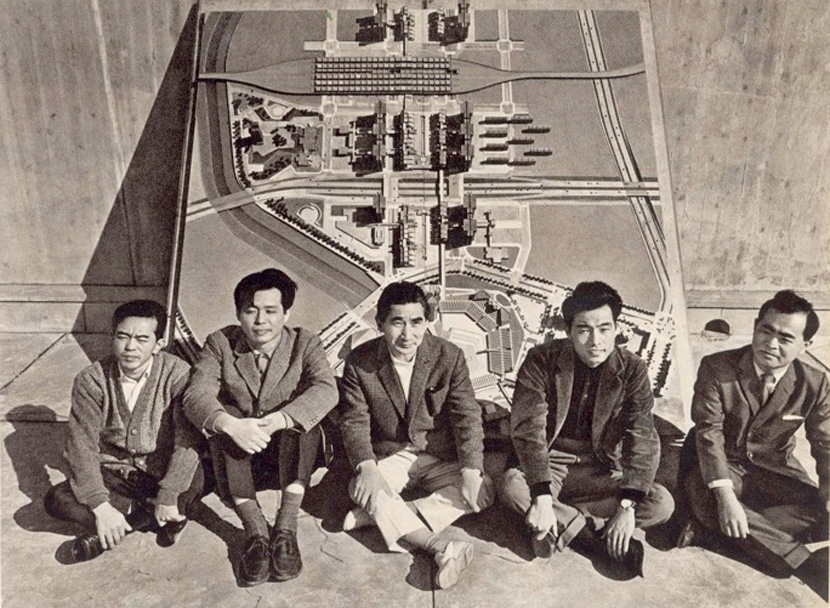

The Kenzo Tange team in front of their model of the eastern area of the city centre, source: tumblr: tststs.

“Therefore a design team was formed, consisting of both Japanese and Yugoslavian architects as well as engineers. Arata Isozaki led the architects team from Tange’s office. Tange’s proposal was based on two metaphorical concepts, the City Gate and City Wall. They referred to the two major elements of the city with distinct characters. The proximity of residential areas to the business district was expected to bring vitality back to the city. The plan for Skopje demonstrated the remarkable continuity of Tange’s approach to city design. The concept of City Gate was based on a linear axis concentrating all urban functions related to communication and business operation. In the middle of this stretch was gigantic gateway structure resembling incoming traffic from regional highways. The axis ended at Republic Square, Skopje’s principal civic space on the River Vardar and surrounded by state and municipal facilities.

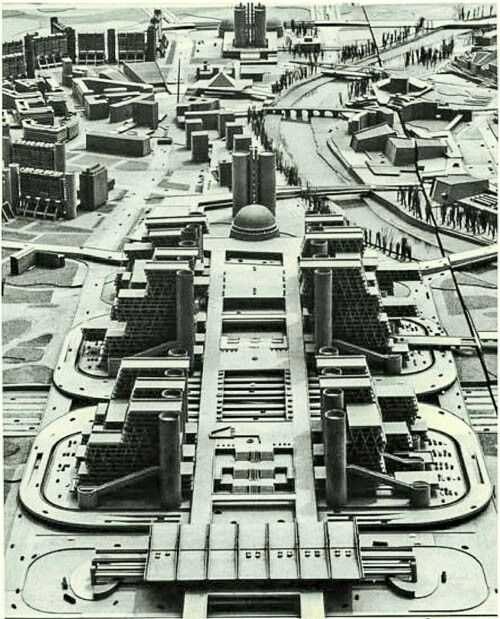

The City Gate literally a gate into the city, would be put in the area where a new train station and gateway structure for highway entries to the city would be build similar to the composite transportation center in Le Corbusier’s Ville Contemporaine, the City Gate was characterized by the convergence of all traffic systems – rail, car, bus and pedestrian movement – and served as the point of transition between regional traffic and local traffic. The railway terminal was designed as an underground structure. Occupying different levels above it were automobile parking decks, transit terminals, and pedestrian zones. The transportation center was joined by a central business district known as City Gate Center, to form the city main axis. Along the axis were clusters of buildings include a number of office towers, a library, banks, exhibition halls, cinemas, hotels, shops and restaurants – all connected to the railway and bus terminals with elevated motorways.

Model of the city by Kenzo Tange, source: tumblr: tststs.

Skopje linear axis stared from the transportation terminal also linked central business district and civic square that formed the backbone of the city. Like Tange’s previous urban projects, the plan for Skopje granted the city infrastructure . monumental scale and sophisticated details, organizing various transportation modes on a three-dimensional system. Following the prototype developed in Kofu, architectures in both the City Gate and the City Wall were characterized by the repetitive pattern combining cylindrical towers housing circulations and services and horizontal inhabitable spaces for residential or business uses. What distinguished the Skopje projects from Tange’s earlier schemes, however, lay in the symbolic meaning of the the urban structures, which the architect had started to explore in his Tokyo Bay project but had not fully developed until the Skopje project. The entire city was bound together with the symbolic concepts of its gate and wall, serving both as programmatic features and metaphors for the urban form. In fact, these metaphors constituted the springboard for the whole design. Tange recalled: We made ample use of this [symbolic] attitude at Skopje. For instance, in applying the name City Gate we not only gave ourselves the hint that we should use something physically gate-like in this area, but we also planted in the mind of the people the understanding that this is the gate through which one enters the city of Skopje. If the design is false to the name, the citizens will reject it.

The City Wall, too, gained fame, and even though at one point the opinion emerged that perhaps the Wall was an obstacle that we should abandon, the people of the city were opposed to doing away with it. They understand the city wall, and it became the center of our image of what symbolizes the city. Now we are told that we definitely should not abandon the Wall. We learned through experience that it is necessary for a variety of symbolic processes to emerge during the operation of structuring.

Tange contended that, through the metaphors of a city with traditional constituents, his plan conveyed meaning beyond the level of physical form and enabled communication with residents and visitors in order to recover the vitality and humanism of the city. Tange’s symbolic return to the classical vocabulary of urban form recaptured some characteristics of Louis Kahn’s 1961 plan for Center City Philadelphia. Kahn called his project Viaduct Architecture. The plan developed from his studies of traffic patterns and earlier projects for Philadelphia, and it envisioned that the whole city would be surrounded by a multilevel highway loop (the viaduct). The concept of viaduct reflected an abstract mastery of Roman forms, as Kahn wrote: “This architecture of movement may be compared to the Viaduct architecture of Rome which was of a scale and consistency different from the architects of of other useful buildings. The viaducts in his plan for Philadelphia, carrying high-speed automobile traffic, defined the boundary of the modern city while allowing unencumbered connection between areas on both sides of the boundary. Several gigantic parking towers standing beside the viaducts served as gateways to the city. Kahn believed that the city would flourish with the viaducts serving automotive traffic and protecting downtown from the invasion of incoming traffic flows. Like Kahn, Tange used the metaphors of classical form to to reinterpret modern infrastructure, providing those large- scale constructions with legibility and cultural significance. Transitions in Tange’s attitudes toward historical context and locality can be detected between his two monumental plans: the 1960 Plan for Tokyo and the 1965 Plan for Skopje. The Tokyo project was dominated by a strong forward-looking aspiration. Tange criticized the city’s existing organization as a “closed structure” which belonged to a “medieval town,” obsolete and dysfunctional for a city of Tokyo’s magnitude. In Skopje, the architect turned to the construction of a City Gate and a City Wall, seeking to recover the meaning of a traditional town. The urban scene in Skopje after the violent earthquake could not be less chaotic than the urban scene in Tokyo in 1960. However, instead of rebuilding the city, Tange tried to preserve the remaining structures in Skopje and used the City Wall to frame the historic areas. He also treated the city’s geographical characteristics in a delicate manner.

Political factors in Skopje also influenced Tange’s decision. The architect later wrote: “Yugoslavia is a Socialist country in which land is not privately held, the city government had sufficient power to make it possible to introduce our total plan.” He believed public land ownership was on his side in realizing his grand plan . Tange’s comment to a certain extent echoed Le Corbusier’s admiration of the authority of the Soviet Union in the interwar period, to which he dedicated his Ville radieuse. In Japan, dispersed private land ownership made it difficult to carry out large-scale urban redevelopments within existing political parameters. Tange’s and the Metabolists urban projects thus remained theoretical speculations. Just as Le Corbusier had turned to Soviet Russia.”[1]

The main post office building, source: tumblr: tststs.