Review / IT WASN’T THEM, IT WAS THOSE BEFORE THEM

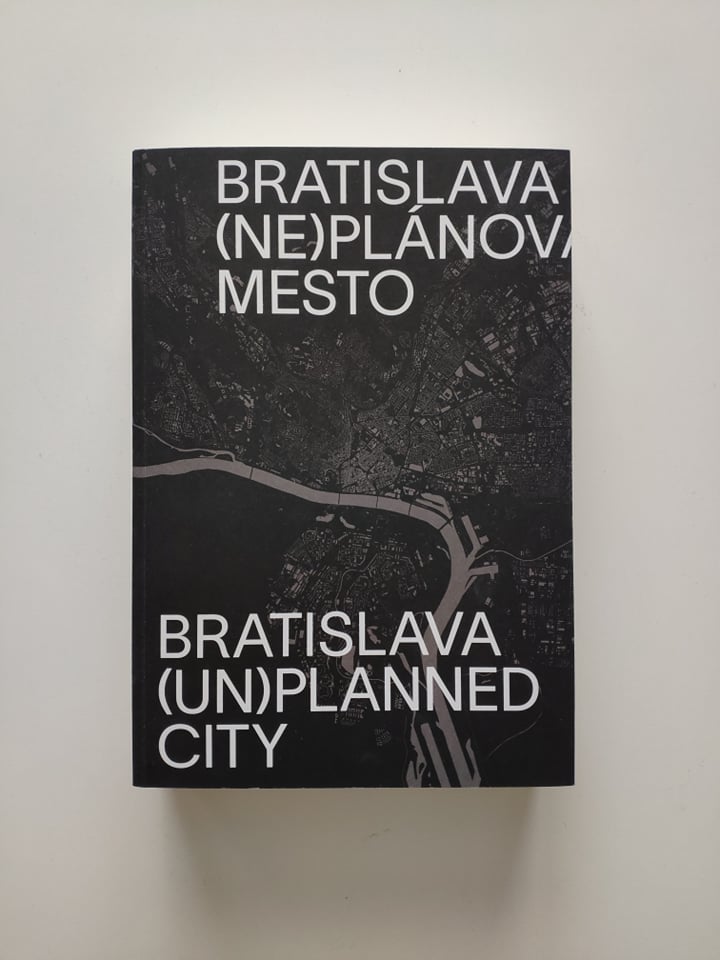

A surprising story of unintended continuity in Bratislava's planning. Henrieta Moravčíková and collective: BRATISLAVA (UN)PLANNED CITY, Slovart, 2020

The relatively recent history of the territory of Slovakia in the 19th and 20th centuries is a strikingly unexplored area. This is true not only in economic or social history, but also in the history of urban planning, not excluding Bratislava. Paradoxically, it was this period, characterised by high urbanisation, population growth and transformation, the development of industry and the associated need for regulation, that strongly determined the structure of contemporary Bratislava. Projects, protocols, competition proposals and texts related to the planning of the capital have been unprocessed and inaccessible to several generations of researchers until now. The reasons for this situation, which are practically still valid today, were described as early as 1932 (!) by the Bratislava city archivist Ovídius Faust: “…data on large public buildings are in the large state central archives, such as in Vienna in the court state and private archives of the former ruling family and in Budapest in the provincial archives. In addition, the chamber archive (Hofkammerarchiv) in Vienna and the archive of the former Hungarian royal court chamber in Budapest also contain precious records and floor plans.” Moreover, the sources scattered in the archives of the former monarchy are kept in German and Hungarian, and therefore their examination is not an easy or attractive task for Slovak historians. Monographs are also a problematic source, as they often did not draw on original archives or contemporary press, but often focused on established explanations, which led to repetition and schematization of interpretation. The study of the development of planning in Bratislava was not helped by the fact that until the 1930s there was no professional architectural periodical in Slovakia that provided contemporary professional reflection.

Incomplete information about the development of Bratislava’s planning has caused the capital to be perceived as unplanned, chaotic, fit for a write-off and a fresh start. Together with the rejection of modernist urban planning practice, urban anti-communism and strong market principles that defined thinking about the city in the 1990s, these views led to a breakdown of trust in institutions. The symbolic culmination of the resignation to development planning was the abolition of the Office of the Chief Architect of the City, including the demolition of its building in 2002. The influx of investment in the following years and weak public authorities caused rapid, poorly coordinated growth and densification, including insensitive treatment of valuable buildings and denial of the city’s urban planning principles and identity.

In this situation, a collective of architects and historians around Henrieta Moravčíková begins their research on the planning of Bratislava: Peter Szalay, Katarína Haberlandová, Laura Krišteková and Monika Bočková, who are not satisfied with a simplified narrative of an unplanned city. The result of their almost ten years of work is, besides numerous articles, papers and conferences, a comprehensive bilingual bible of the urbanism of the capital city – the book Bratislava (nn)planned city, published in a beautiful graphic form by Slovart publishing house. As the authors declare, the aim of the research was not only to summarize the knowledge about Bratislava’s planning, but also to strengthen the position of the public interest and the ability to compete with investors and market players in deciding the future shape of the city. Because the latter have bent regulations in their favour throughout the period under study.

Weak city, leaky plan

Although Bratislava’s first regulatory plans worked with themes of modern urbanism such as zoning, traffic systematisation or the organisation of urban streets, the plans failed to be implemented because decisions on new construction were taken by the city council on an ad hoc basis, based on the demands of private developers. There were also not enough resources for expropriation and the application of grand plans. There was criticism of the contractors of the projects, and new and new plans were drawn up, which included direct suggestions from the factory owners. Even at the time when the city officials had in their hands the regulatory plan of the town hall and also the second, Palóczi’s plan of 1917 (which was never officially approved), they “weighed in each case the possibilities offered in both plans and decided according to which solution was considered by the majority to be the right one”. New partial and conceptual competitions were launched, the proposals were not implemented, everyone was dissatisfied, and planning proceeded in a continuous pause. Bratislava avoided being bound by rules and found it difficult to reach consensus between groups. It makes one smile how many parallels with today we observe in this story. Neither 150 years ago nor today is it possible to enforce plans in their entirety in the capital. Visions divide society into camps, plans change on the fly based on moods or capital, each new city leadership rewrites the plans. The result is a collage of different approaches that shows that the endgame just isn’t going our way.

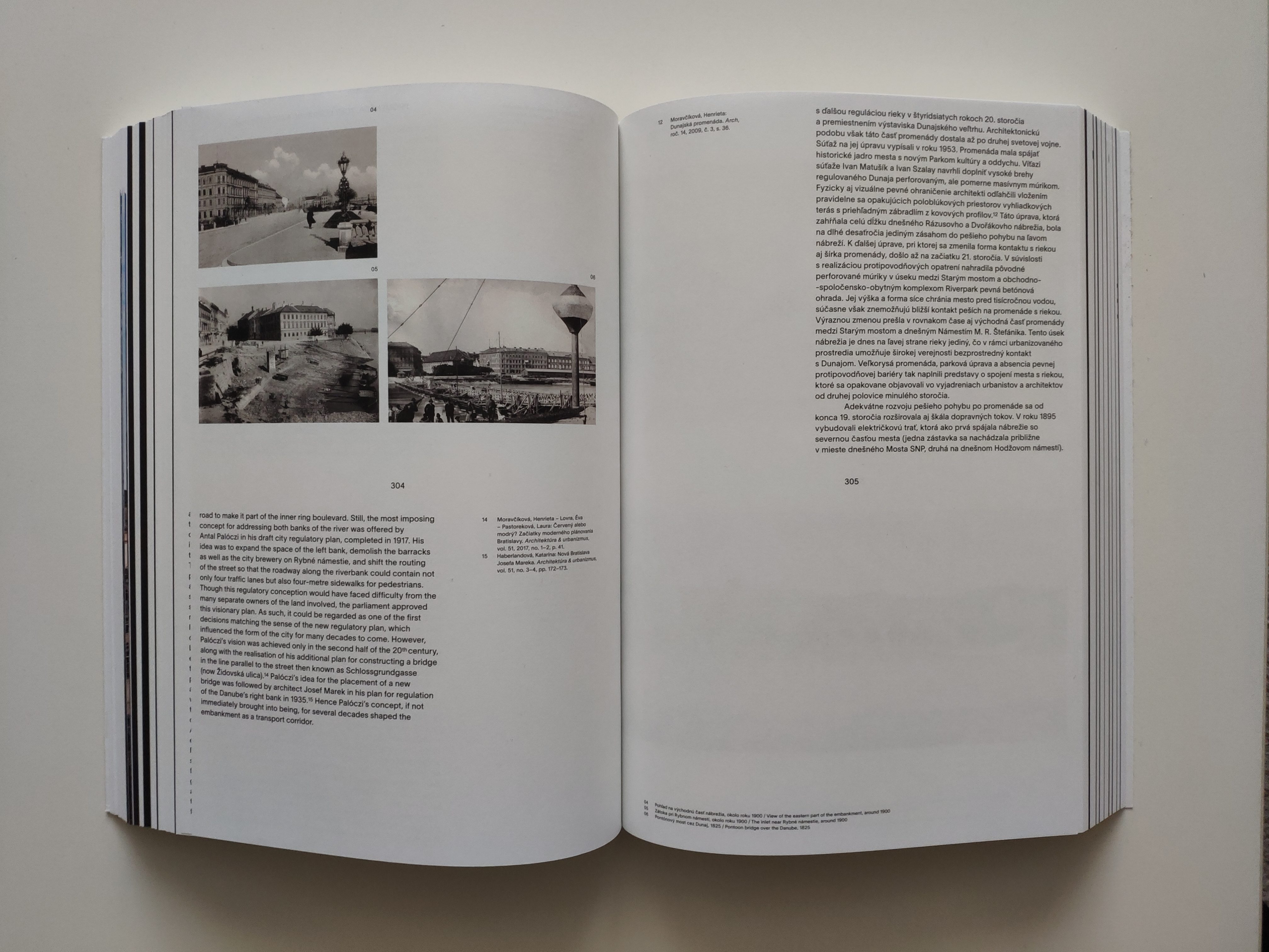

A prerequisite for overcoming the childhood illnesses of spatial planning is a good knowledge of the immediate past. The book Bratislava (un)planned city is exceptionally helpful in this respect. It is the first time that hundreds of materials on Bratislava’s planning history have been compiled to provide an overall view of the city. In addition to internal City Hall documents, texts, competitions, commentaries and contemporary press, it includes the main urban planning documents from the first regulatory plan of the city in 1774, through the first modern plans of 1906 and 1917, several inter-war comprehensive plans of the city and smaller regulatory plans, post-war guideline zoning plans up to the current zoning plan, and many more. Perhaps the greatest contribution to further research lies in the application of a method of a kind of critical digitization, layering documents from different periods into the form of a spatial model, which the authors analyzed and compared with the real urban structure. In this way, they could verify the consequences of planning (mostly depicted as a 2D map) on twelve specific locations, urban situations. They divided these into the categories of mutation, flow, habitat, container and terrain vague, following the example of the architect and urban planner Ignasi Solá-Morales, and used them to explain the turbulent changes that the case studies represent.

The phenomenon of unintended continuity

The team around Moravčíková concluded, in the context of comparing planning on paper and in space, that “several urban or architectural solutions that determine the current form of the city and are considered to be the product of informal planning are actually the result of the transfer of information from different historical layers of formal planning of the city”, which translates to the fact that Bratislava is not so unplanned after all. On the contrary, it is rather over-planned. Bratislava is not a city that grows without a plan, “but a city where competing, contradictory or, on the contrary, mutually supportive plans are implemented, which are at the same time applied piecemeal, sometimes even differently from the way the authors envisaged them.”

The capital is characterised by a phenomenon of unintended continuity – an undeclared but legible continuation of visions across the political establishment. However illogical it may seem to us, the position of today’s Old Town Street was not invented by the communists, but by Antal Palóczi. The demolition of Podhradie was advocated by Dušan Jurkovič and the regulatory study of Greater Bratislava during the First Republic. The idea of preserving the Castle, the position of the university campuses or the bridges over the Danube also survived from earlier plans and was not set by past governments. The impression of discontinuity may have grown because the creators of the new planning documents, who applied the basic ideas of their predecessors, did not refer to the older plans. It is only by comparing the documents that we find that the ideas continue. But did this continuous character of Bratislava’s planning stem from a detailed but hidden study of the documents or only from incomplete information about the development of urban planning? The planners may have been inclined to come up with new solutions, but determined by external factors, the topography, the location of the city by the river, the position of the circular class, their plans still became (unintentionally) similar to those of the past. The partial or no implementation of the land-use plans in Bratislava can be perceived in two ways. We can notice all the shortcomings of the city, the constant destruction of its identity, its incoherent character, full of the torso of unfinished plans. Or, on the contrary, we can look for beauty in its imperfection, accept its discontinuity and even see it as a typical feature. We can appreciate Bratislava as a fascinating laboratory of different urban approaches, a vehicle for new beginnings. The overview of the story of the capital’s development offered in Bratislava (un)planned city anchors thinking about urban space in its historical context, offering a pathway to both approaches.