Essay / A FLAW IN THE SYSTEM OF THE IDEAL CITY

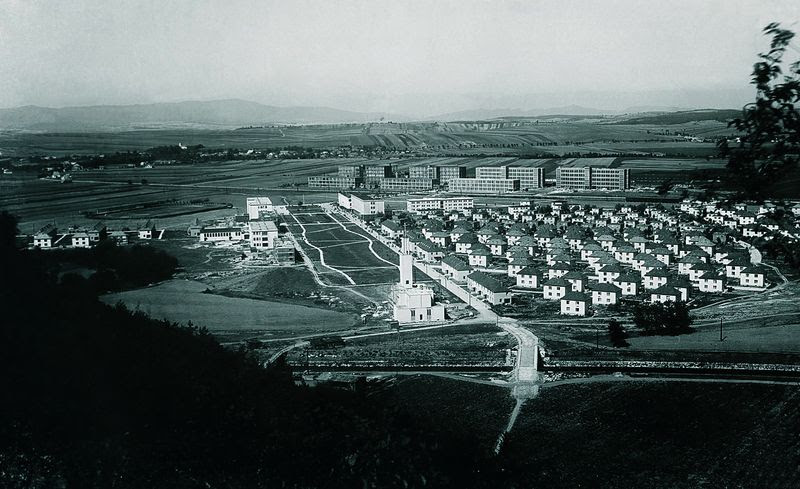

A year ago it was still there and did not escape the attention of even an inattentive visitor. Today it remains only a hole in the centre of the town, not an ordinary town, but the only ideal industrial town in Slovakia. The casual visitor or onlooker may be a little confused. The tower has suddenly become a pit, the monument an anti-monument, the clear memory just a recollection of whether the 13-storey block of flats in the middle of the square in Partizánske was ever really a reality. Let’s just say that the “high-rise”, as the locals call the building, can be seen as a flaw in the city’s system. Baťa’s architects planned it as an efficient organism for 5 – 15,000 inhabitants, with zones of work, living, services and leisure, accessible to each other on foot, with well-thought-out details and clear rules for movement, living and working in it. Excavation work began on 8 August 1938. This day is considered the official date of the creation of the town called Baťovany, which was originally to be the site of a factory for the production of shoe machines and bicycles.

Partizánske, map of zones.

When, at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, the need for another boarding school for Baťa’s well-adjusted type of education appeared, to which students from all over the country were flowing, a decision was made that changed the character of the town significantly for more than half a century. This mistake, gesture, scar, or just another layer of the city, was suddenly something that had to be dealt with, arousing the passions but also the resistance of the locals, for whom the (inherited) memories of a well-functioning, smoothly flowing city with rules and no obstacles are still the strongest motivation to defend it. The building has undoubtedly charged the strong position of the city’s layout and its functions, but its relationship with the strata of the Baťa industrial city is by no means as clear-cut as it appears at first glance. At times it affirms the original plan, at others it defuses, blurs or denies it in order to strengthen its own position elsewhere. And sometimes it may even seem to mock the ideal city outright, only to disappear from its horizon altogether, leaving only an embarrassed trail and a number of untold versions of the future.

After demolition: view from the square on Karfík’s church, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

Confirmation

A new prefabricated building, the student dormitory, rises in the centre of the square in 1963 in the context of the other Baťa dormitories. It is nestled between the existing dormitories for ‘young men’ on one side of what is now SNP Square and for ‘young women’ on the other. Functionally, therefore, it is not out of place, and at one point it may even seem that its location has a pragmatic and efficient basis, just as Baťa’s urban planners would have wished. The dormitories are connected to each other, or are connected by the new building, apart from the fact that some of the earliest versions of the city’s regulatory plans by the architect and urban planner Jiří Voženílek from the 1930s actually indicate a building on the same site. What it would have been according to Baťa’s architects, however, we can only surmise today; it was omitted from subsequent regulatory plans. In 1962, the railway station building was also completed and other buildings were being constructed near the centre, so the construction of the prefabricated dormitory does not appear from this perspective as a purely solitary intervention without context.

Demolition, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

Even Baťa company itself has been active in the development of the panels since the 1940s. In Zlín, experimental 1-3 storey buildings were started with the aim of replacing the labour-intensive brickwork of partitions and walls with bricks. The architect Vladimír Karfík, experienced from his work in Bata’s construction office in Zlín, even supervised the construction of the first prefabricated panel building in Slovakia, a 6-storey house on Kmet’ovo Square in Bratislava in 1955.

In the context of Baťa’s architecture, the high-rise building as such is nothing exceptional. Right in Zlín, the hometown of Baťa’s visions, Vladimír Karfík built a 16-storey office building, one of the first high-rise buildings in Europe, nicknamed the Zlín skyscraper or 21 – Twenty-one. Karfík, the head of Baťa’s construction department, found a lifelong passion in high-rise construction. He caught it especially in his studies with modernists Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, or right in Chicago, at the Holabird and Root studio, which concentrated on skyscraper projects.

Demolition, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

Denial

The high-rise building, located in the centre of an urbanism that has its own specific rules, comes up with confrontations in which it (seemingly?) acts as an opposition to everything that has been defined in the city until then. It outgrows it, it struggles with it, it denies it. The urbanism of the ideal industrial city has clearly defined rules. A system not working with a set of these principles, entering into such a coherent or closed programme, is confrontational by principle alone. And if a new system emerges at the very centre of such urbanism, it draws attention to itself and demands new and new interpretations of its presence in a context that does not reckon with it, and that is not set up for layering and mixing.

During demolition, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

The reinforced concrete skeleton became the basic construction unit in Baťa’s construction. It uses a column span of 6.15 x 6.15 m, or 20 feet, a reference to the adoption of the construction system from the United States. This well-known Zlín module transcribes the spacing of the concrete columns of American factory buildings into the metric system. Such a design allows construction to be done quickly and efficiently. Baťa architects used three such bays for the width of a factory building and thirteen bays for the length. The scale used in the construction of the halls is also carried over by the architects into the rules of urban planning. It was the spacing of the 13 bays that determined the width and length of the square in Partizánske (multiples of this spacing), the length of the social buildings that flank the square, and the spacing between buildings. In the case of a high-rise building we naturally do not find such parallels; the building is a solitaire with an autonomous system of panel technology. The grid or grid consists of solid prefabricated elements, load-bearing panels and partitions.

The diagram of the use of the Zlín module in urban planning, according to P. Andráši’s diagram, was developed by the authors.

The prefabricated building here comes as a solitaire to the finished city, which is a rather rare situation, as we know from the history of the construction of prefabricated houses and housing estates that they were mostly built without the necessary infrastructure and amenities, in larger complexes and structures, basically on greenfield sites.

The original Baťa urbanism also retains the height of the buildings, which is exceeded only by the church tower. It rises at the end of a long square and encloses the town from the south. Already the position of the church and the choice of its architect, who is again Vladimír Karfík, indicate the dominance of this building. The ingenious technical solutions of lighting or heating, the use of a reinforced concrete skeleton, or the distinctly vertical character of the façade only underline this fact. It was the high-rise building that robbed the church of this specific position. The division of the square, the obstruction of the view of the church and the significant height created a situation that suppressed the dominance of the church in urban planning.

Red Street (the first realized street within the construction of the colony) vs. high-rise building, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

The most striking denial of the previous context of the city is thus the disregard for high-rise development. In addition to the 3- to 4-storey buildings, there is a tower with 14 storeys above ground and one underground storey. It cuts the square in two, forms a visual barrier, the church is no longer visible from the community buildings.

The prefabricated building enters in the middle of a concept that represents everything that was uncomfortable for the regime in which it was built. It could also be seen as an ideological symbol. After the advent of communism, the name Baťa is associated with exploitation, it is denigrated, it is a history that is denied, often fabricated. A capitalist, after all, cannot remain a hero, even (or rather especially) if he was the founder of a city. In the literature of the period, when describing the founding of the city, there is always a section that portrays Baťa as an exploitative capitalist firm that is not worthy of claiming allegiance to. Placing a building in the very centre of the city to symbolise the new regime is an excellent demonstration of power. A building that will be visible from every corner of the city, a building that will block the view of the church, one that will be created by a new technology. It will become a symbol of all that is new and a negation of all that is old. It will be the planting of a triumphal flagpole demonstrating the arrival of an ideology that has all the attention on it.

SNP square before demolition, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

It seems that denying context also means strengthening one’s own position. The prefab is an (infinite) multiplication of its footprint as a Manhattan skyscraper. It becomes a city within a city, an island unto itself, even though here, in the middle of a green square, there is no pressure on its verticality. It is like a watchtower that controls the life of the city more than Baťa’s manual. Koolhaas says that once a certain critical mass is crossed, every building becomes a monument. One does not need to cross any magic threshold to discover that the mass of a prefabricated building far exceeds that of just a few-storey building in a square. Does the prefab thus become an automonument? Koolhaas argues that this type of monument does not represent any abstract ideal or exceptional institution; it is not a monument but an empty symbol, celebrating only its own existence. By its presence, the prefab in the middle of the city also breaks the inhabitants out of the stereotype, out of the usual meticulously set day of an employee of the former Baťa factories, demonstrating power and progress in the form of a new type of construction, making it a prototype or even an experiment. It thus refers to the ideal of prefabricated construction, of which it is one of the earliest prefigurations in what was then Czechoslovakia. Could it be a monument to these prefabricated buildings? Is it actually too late in the 1960s, 8 years after the first ever prefabricated house was built in Bratislava? Is the ideal city an urban utopia? Is a pragmatic utopia an oxymoron?

Erasure

Erasure occurs when we focus on the person and their bodily or visual experience of the city. The generous central square follows the garden cities and is now conceived in different types of parks, namely the park with a central water feature in the northern part in front of the House of Culture, the “official” and strictly geometrically arranged type with the SNP monument flanked by a tree line, and the wilder park with an almost rural character stretching in front of the Karfík Church. The apartment block disrupted this very continuum or sequence of experiencing different green environments when it massively disrupted this experientiality and stood in the way of it without any permeable filter. The square is no longer a single entity; the building has cut the visual connection between the two structures that delimit it, the house of culture and the church. The distinctly horizontal movement in the city has thus been disrupted by the vertical movement inside the tower, so symptomatic of (large) cities. The apartment block becomes a kind of observation tower with a whole new opportunity for bird’s eye views of the city.

SNP square before demolition, view from the House of Culture towards the church, photo: Katarína Janíčková.

Coexistence

These two systems, the ideal city vs. the prefabricated house, are the dual presence of powerful systems or figures. In trying to understand the city as a whole, they elude each other, one flickering into the other without an interface to soften the differences or blur their boundaries. Neither wants to be a backdrop for the other. But could they live in symbiosis? In a mutually beneficial coexistence? Maybe all they had to do was look closer, preserve the existing qualities, and add what was missing. Ownership relations could have been an advantage for such a transformation. In our country, most of the flats are privately owned today, but the prefabricated building in Partizánske belonged to the city. A similar situation of an apartment building from the 1960s was solved in Paris with the winners of the competition for its redesign, the architects Lacaton & Vassal together with Frédéric Druot. The key was the replacement of the non-load-bearing façade cladding and the repositioning of the lightweight steel structure, creating spacious and light-filled apartments with balconies and conservatories. The addition of an extra layer reduced energy consumption and created a high quality space between the interior and exterior. And most importantly, at half the cost of demolition. Similar types of transformations are happening all over France today under the baton of the aforementioned architects, and even while they are in full operation, with a clear vision not to demolish but to add, transform and reuse.

We don’t have to go far, we have a nice example of redesign of a panel building in Rimavská Sobota by gutgut studio. Part of such redevelopments is often a concern for their public space, adding gardens, greenhouses or parking under pergolas. The issue of social housing is particularly associated with the peripheries of cities, and therefore their improvement is an injection with immediate effect.

Although the prefabricated building and the ideal industrial city seem to work separately, one cannot be separated from the other. Here the public and the private bump into each other from every side, the space of the square meets the spaces of rooms and apartments without mixing in any in-between space or filter. The collective and public interest of openness and accessibility clashes with individual needs for intimacy or the social bonds of community life.

Construction of a high-rise building using sliding formwork, source: Archives of the Partizánske Municipal Office.

Confusion

The most (un)surprising dimension of the high-rise building remains its ambiguity. It constantly forces us to question the claims we have made, both in affirming and denying its existence. If we claim that the building’s location follows the first building plan designed by Voženílek as Baťa’s architect, we have to consider the possibility that in the new political system, which is highly critical of the history of the city’s founding, no such follow-up is attempted by architects (and municipalities). The latest Voženílek plan envisages further dormitory construction to the west in direct continuation of the young women’s dormitory. Thus, if the location of the high-rise dormitory follows the first Voženílek plan, the later one contradicts it. Nor can it be argued that the building is without context on this site, as it originally served as student accommodation and is a continuation of the two existing dormitory buildings. We refer to the height of the building as negating the high-rise development of an ideal industrial town. However, towers are not unusual in Baťa architecture. Even the industrial, factory part of Partizánske has its office building. And if we call the panel construction too contrasting to the brick Baťa construction, it should be noted that the Baťa company has been experimenting with panels since the 1940s.

After the fall of communism, on the one hand, we want to remove the “scars on the faces of our cities” in the form of housing estates, but on the other hand, we see the uneconomic and brutal nature of such solutions, nostalgia and a compelling argument that the lifespan of prefabricated buildings is not infinite and at some point they must necessarily be reconstructed, transformed or rehabilitated.

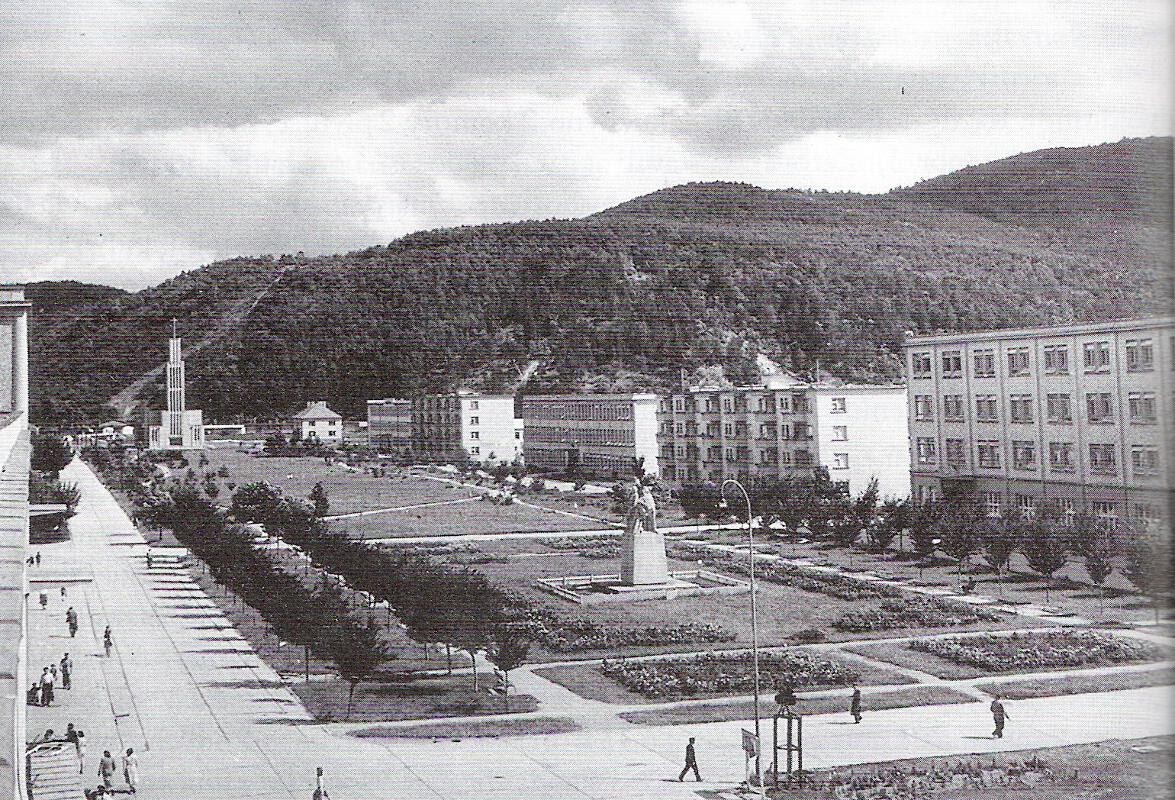

The square before the construction of a high-rise building.

Equally, we can question the demolition of the house itself. In the 1990s, the dormitory became housing for families from difficult social circumstances; the dormitory rooms began to serve as small social apartments. However, the building is located in a beautiful park and square setting with an emphasis on pedestrian movement, with the best views in the city. However, it is often deliberately damaged, the flats are of an increasingly lower standard, and in 2017 the municipality closed the building and demolished it three years later. Over time, the term “hollowing out” comes up in conversations about the high-rise. This refers to the behaviour of residents from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. There is a further unease here, which relates to its end. The story of a building that obstructed the view of the church is used in the communication of the local government. It is an argument that distracts from the problem at hand, it is an argument that works. But what fate would await the building if it had not become social housing with a distinct lack of systemic social work (more of a community-wide problem than a local one)? Would its removal be called for even in a scenario with standard housing? And what other program scenarios would this tower be able to accommodate?

Was the building really built to obfuscate and obscure? In its creation, the view of the church, an architectural analogy of faith based on love of neighbour, was obscured, and in its removal and re-discovery of the view, the social problem of the lack of addressing the situation of marginalised groups in the city is again obscured.

View of Baťovany from behind the river Nitra.

The prefab has brought too many problems to the middle of a small town. A mass of people that is hard to control in a regulated place where they are to be obeyed and represented. A distinct mass into the void of public space, but one that is a fluid assemblage of different ideas, environments and conditions of openness or accessibility rather than just a free space to stop. And perhaps it was enough to see in the problems the potentials for new situations that needed to be named, cleaned up and supported. Or is Partizánske resisting other visions and any new form of urbanity, its internal stumps and extensions? And what is actually the urban vision of the 21st century? Are we afraid of the future and spasmodically defending the past as an open-air museum that is crumbling under our hands? Or are we not paying enough attention to either the past or the future? And could the forthcoming competition to redesign the square be a real opportunity to move beyond the status quo?