House / HLAVNÁ 25, BRATISLAVA

We talked about the house of Olga and Imrich Vanek with Svätopluk Mikyta (SM) and Zuzana Bodnárová (ZB) from Banská Stanica. The house was photographed in November 2015 by Hynek Alt. The interview was conducted by Ľubica Hustá.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Sväťo Mikyta was friends with Imrich Vanek and was a frequent guest of him and Zuzana. After Vanek’s death (2015), together with his family, he is partly taking care of the house and fulfilling Vanek’s dream to turn the house into a museum of Vanek’s work and a space for residencies of young artists working with ceramics.

When did you first visit Vanek’s house and what was the first thing that came to your mind when you walked in?

SM: It was in 2004, shortly after our second intensive meeting at a symposium at the porcelain factory in Dubí. Imrich and his wife Oľga welcomed me on the ground floor of the studio. Everything was perfectly prepared. There were sandwiches on the table, open wine, a kind of mini reception for three people. At that time I was just getting to know Vanek’s work and this was the first friendly visit in private, which they both protected very much from the outside world.

What is the history of the house and who designed it?

SM: Šárka Svobodová, an architectural theorist from Brno, whom we invited to participate in the project of the upcoming book about Imrich Vanek, has written an extensive text about the house and the context of the time. Among other things, she says: “At the time when the Vaneks decided to start building a house with a studio, they were straddling several cities. Imrich Vanek gained a working background at the RAKO ceramic factory in Rakovník, where he had the opportunity to fire large-scale ceramics. However, they lived in Bratislava in a block of flats in the then new housing estate Štrkovec and they also kept an apartment in Prague, where Olga came from. The need for a studio of their own certainly played an important role in their motivation to live in their own house. At that time Imrich Vanek had already completed a number of architectural projects, all in Slovakia, and in the early 1970s he was working on about two large commissions a year.” And about the authorship, he says: “The first sketch for the Vaneks’ house was created by the architect Milan Kukelka. However, due to personal disagreements with Olga, he allegedly withdrew from the project. The surviving original plan documentation from 1973 thus proves that the Vanek family house was designed by the Slovak architect Štefan Svetko.” If all goes well, the book, whose second text was written by Professor Belohradská with photographs by Illah van Oijen and Hynek Alt, should be part of a forthcoming exhibition at the East Slovak Gallery in Košice in November 2020.

How does the house look from the street?

SM: From the street you can easily miss the house. It’s up there somewhere, high up, and you can only get to it by a narrow, rather steep staircase. If you cross it, you are already elsewhere. The noise of the trolleybuses heading to Koliba stays down. The thin façade, the first signs of the author’s ceramics on it, and in front of the entrance a larger-than-life figure of a kind of ceramic Golem, the guardian of the house, which, according to Imrich’s story, was spectacularly fired on coke in a pit dug right in front of the house in the presence of the firemen.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

How is it spatially arranged?

SM: The working, representative and private spheres. It all has a place here and interconnects with each other in a strong vertical. You enter the house and you have the choice to go to the working – studio area or to continue to the representative areas. If one were to go downwards from this level through the interior of the house, one would reach the ‘dirty’ storehouse of clay, glazes, the ceramic kilns and the deposit of works. In addition to the main, formal routes, you can use communication shortcuts, ramps, small staircases and narrow corridors. The technical facilities of the work unit included an industrial elevator for moving bulky materials and finished works, which ran straight down to street level. I have personally seen it in use only twice, when Imrich used it as a shortcut, and no one has been able to lower it since. If you went up a level from the ground floor, it took you to the formal rooms, called the banquet hall and gallery in the architectural plans, with access to the exterior. The upper floor remained closed, private to the visitor. Only Imrich and Olga and their cats could go there, they bred a number of them with great passion.

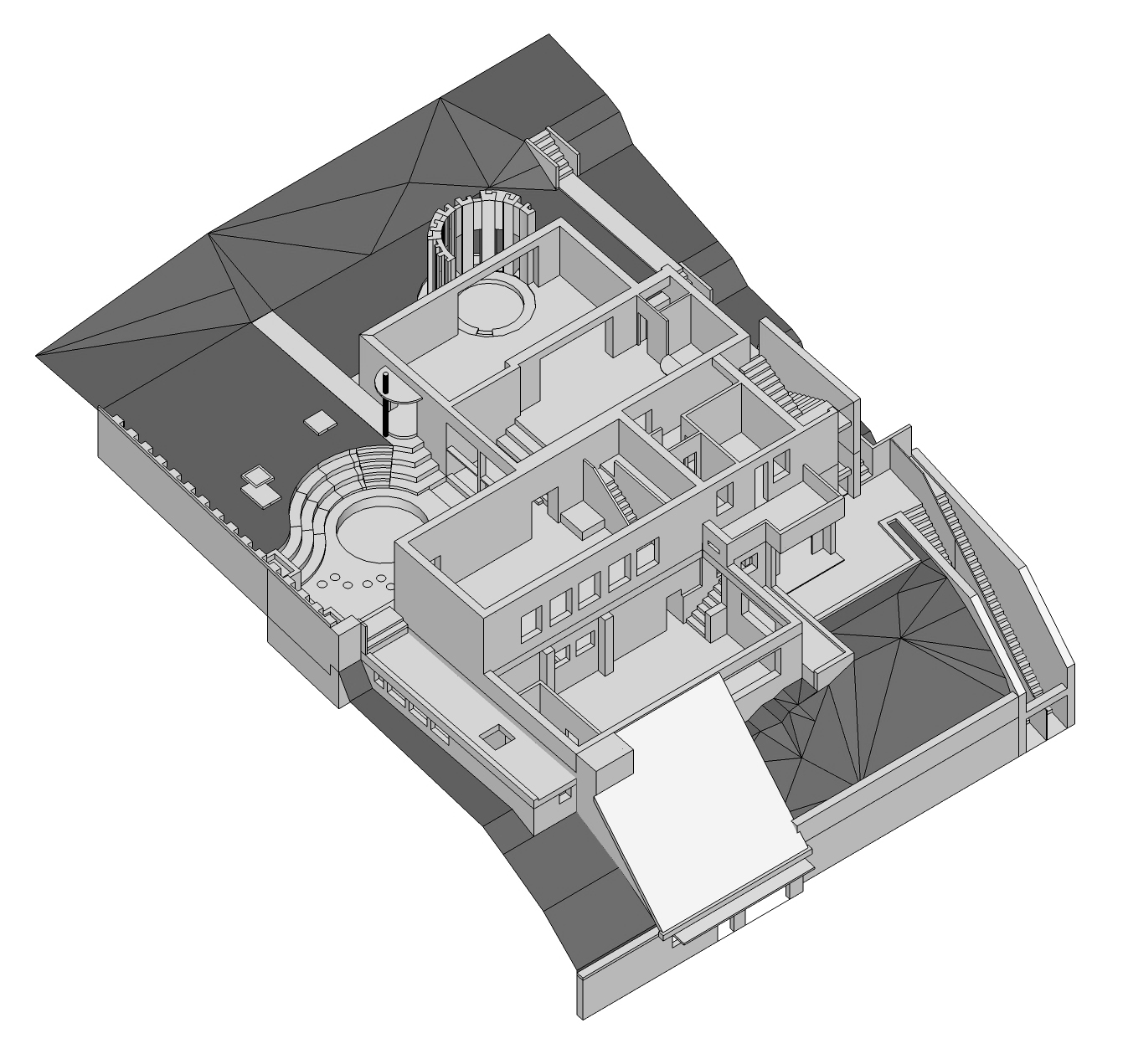

Source: nla architects.

Wherever in the house was his artwork asserted – did Vanek realise any monumental works here too?

SM: The author’s work can be seen everywhere. Everywhere, everywhere, everywhere. Smaller details, also large bulky sculptures and relief monumentals. I think he tested things here on private ground, verified things before he made them outside. On large surfaces, floors and walls we find hand and machine modelled and painted tiles. There was no escaping the author’s ceramics here. I remember that the ubiquitous visual and material made an immediate impression on me. And there was still a level of “decay”, semi-decay and a kind of building incompleteness that was directly related to the social changes in 1989.

What was the idea of the use of the house before 89?

SM: From the beginning, Imrich planned the operation of the house as semi-public. Even when it was being built, it was thought of as a place that would one day open its doors to people interested in art and culture. With one exception, none of this has come to pass.

What was the exception?

SM: In 1994, there was a side event to the meeting of the participants of the International Academy of Ceramists (I.A.C). There is a series of photographs of the whole event which show how suddenly all the details of the garden found their meaning. A receding staircase of ceramic segments served as seating, fountains with running water cooled the atmosphere.

Let’s go back inside, to the gallery.

SM: The most representative spaces in the house aspired to represent his work and to welcome the company, the curator or the collector – for example, the unfinished large banquet hall with gallery had distinctive sculptural realisations; the wall with the Golden Throne was situated between the studio and the banquet hall.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Warehouse of works, photo: Hynek Alt.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

The Golden Throne, photo: Hynek Alt.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Imrich Vanek and Svätopluk Mikyta (2015), photo: archive of SM.

The Golden Throne?

SM: At the centre of the monumental narrative relief, where, in addition to the author and his wife, there are also cats, is an integrated “sitting” in high relief. A golden throne with a target – a powerful, irrational element in a villa emerging in the grey era of socialism.

ZB: The Golden Throne struck me as some kind of precious excavation that is a reference to a long-vanished civilization.

SM: That’s what it appears to you, perhaps, from what the throne presents as such. For me, there was a glamour and hyperbole to it, something bohemian, bon vivant, but at the same time ironic. We never talked about it, it was just there and it shone “it” at all times as some clear, given constant. Vanek also liked and often used gold and platinum glazes on large units and complete objects. Now and then he mentioned to me that people were always taken off guard, charmed and taken aback by it. He liked to offer them the opportunity to sit on his throne. I also read a certain amount of irony in this. To build a golden throne in a grey, unfinished villa. But surely the chair/throne was not a design, but a crude, sculptural piece of work.

ZB: And when you talk about glamour, or that bon vivant feeling of it, this character’s life after the Velvet Revolution took more of the opposite direction.

SM: Yes, it ended after the Velvet revolution. The public architecture contracts ended, the system under which he was surprisingly free to create, earn and travel ended. The incredible work commitment that Vanek pursued and adored was over. He also had several monumental works in different parts of the country going at once. And he was moving behind them in a very action-packed way. By not having a family of his own, he was not limited by anyone or anything. After ’89, he seemed to have turned off eighty percent of the gas. By the end of his life you could feel that he had incredible energy, potential, he had the drive, the overpressure to create, he just had to deal with other, existential things. Quite simply, and I know this too, if you want to make on a large scale, dimensionally and materially, you can’t be limited by the amount of electricity you need to fire it, or the cost of it, you can’t calculate whether your pension comes out at the end of the month, for food, you can’t limit creation and its form to practical life.

We’ve already gone through the office and the representative part. Where were the private parts of the house?

SM: On the top level of the house, all the way up, were the private areas, a simple living room – a TV room with a fireplace, a bedroom, a generous bathroom with a so-called Roman bath, and a small, very space-saving kitchen, which consisted of a counter where you could chop, cook, and there was a small table for a small breakfast for two.

ZB: That spatial disproportion is interesting. The private spaces were purposeful, austere, actually minimal, such a basic microcosm for two people. And the representative ones seemed to have no limits.

SM: Yes, more important than the size of the kitchen, which had “prefab standards”, was the possibility to go straight out onto the terrace, which was roughly thirty square meters, and enjoy an almost 360-degree view of Bratislava. This is the exclusivity that made sense for Imrich. Our communication intensified after the death of his wife Olga in 2013, when I had the pleasure of having dinner with Imrich on that very terrace several times. He would roast a duck or cook some smoked knee, open some red wine and we would sit there, discuss art, look down on Bratislava. I must add that it was the dining, everything that we drank and ate from – that is, plates, cups and so on – that was always his own original porcelain.

Did he also have ambitions as a designer? Were there any other more design-oriented designs in the house besides ceramics, e.g. furniture, lighting fixtures?

SM: Certainly not, and I know that from many conversations we had together. Vanek didn’t want to be a designer, he wanted to be a sculptor. Now and then he made an award, or a mug for a mug symposium or a tile, but his basic ambition was clearly sculpture, he was a sculptor, and he always wanted to put the perception of ceramics as a material on the same level as bronze, for example, or other sculptural materials.

Did Vanek have other hobbies besides creating?

SM: He didn’t. He was absolutely devoted to ceramics, he was literally obsessed with it, absorbed by it. As well as his relationship with Olga. The only thing that can be considered a hobby is breeding cats. As an allergy sufferer, I suffered quite a lot from their presence, and Imrich tried to accommodate me by always diverting them to other rooms before my visit. The only thing he knew how to leave the ceramics for was travelling. He saw it as a source of updating views, attitudes, knowledge. Like me. Already during socialism he was very active, within the limits of his possibilities, in travelling. He brought home a lot of books, catalogues, experiences. It was clear from our conversations that when they travelled somewhere, he, like his wife Olga, insisted that it had to be classy. He used that word a lot – he hated substitutes, plastic utensils, he stressed that. Service was always ready, even when it wasn’t necessary. They wanted everything to have a standard and they emphasized it even during trips abroad. The hotel had to have a standard just like the show. He tried to carry this approach into his work, I mean quality, not snobbery. Exclusivity, yes.

What other materials were or are in the house?

SM: Everything there is oversized, customized and subordinate to the clay. The latter is the basic medium of expression. If only the walls and clay, ceramics and porcelain were left, it would look very interesting. Only artistic realisations from monumental to smaller objects to plates and mugs, his utensils that were commonly used in the home.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

He remembered that he didn’t garden. So what did the garden look like?

SM: The garden was conceived again as an outdoor party space with two fountains and some monumental realisations with facilities for relaxation and barbecues. No flower beds or growing vegetables for salad. However, everything was relentlessly taken over by the wild encroaching nature, which neither Imrich nor Olga could fight. When we organised a symbolic mowing of the garden in the summer of 2019 as one of the side events to the exhibition at the TIC gallery in Brno (Imrich Vanek: …when ceramics wasn’t cool yet / TIC gallery), only a few people came. We experienced what perhaps the Vanek family once experienced.

What does the house look like today and what is the intention of its future use?

SM: The house is in an in-between stage, within reason, with a positive future, with cultivated heirs from the family who have the ambition to respect his wish to make his sculptural work available to the public. They are also open to more progressive plans, which I see in linking a permanent exhibition with a vibrant residential centre. After Imrich’s death in the fall of 2015, architects Halada and Bradňanský of Studio N/L surveyed the house and created a renovation project. The axonometry of the house reveals at first glance the complexity of the building. The architects simplified the individual functions and added a temporary housing function for the resident in the working part. The idea, which was shared by the heirs, is that there should be a living ceramics residential centre alongside the Imrich Vanek Ceramics Museum. Our experience from the residential centre in Banská Štiavnica is an example of how this could work on an international level here.

How did Vanek perceive the position of the work in public space?

SM: Quite fundamentally, he showed it with all his work, with all his efforts, he actually gave his whole life to it, and there is a lot that remains of him. I think that the realisation of the work in public space was not pre-planned, rather it was a gradual spontaneous development. After the first successful collaboration with an architect, there was another one, then he got absorbed in it and adjusted to it. The works that are still in public space today have lost none of their freshness. Unfortunately, there are also those that the new owner, in the interest of modernising the building or its energy efficiency, has covered with plasterboard or straightforwardly “deinstalled” with a hammer and a sledgehammer.

In the context of works in public space, how did Vanek perceive the change that came after 1989?

SM: He didn’t despair. Of course, it came upon them and they felt it. It was probably disappointing, but they didn’t lament. He never spoke on the subject, he never opened it up in debate, we just talked occasionally about the fact that times and laws had changed, the market had changed. I guess the times sapped them and led them to the point where they didn’t continue because they couldn’t. And what I think weighed on them more was more disinterest and not being appreciated. On the one hand, his house was full of the work to which he had devoted his whole life, on the other hand, there was no interest in it, no reflection on it. And this was frustrating for the author.

Why is Vanek close to your heart?

SM: I am an author two generations younger, with different ideas, plans, ideals. My work has a different starting point. With him, I felt and saw what it could be. What it is like when an artist has not only talent, but also conditions and his own artistic “engine”. We took each other as equals, in discussion, in work, in creating together. We initiated our collaborations with each other and planned for more. The intense friendship that arose between us by chance had meaning and value for both of us. It was only in retrospect that I realised that this was something special. The Vanek family lived a very closed life and did not communicate with anyone else. I also always perceived a kind of personal parallel between his life with Olga and mine with Zuzana.

Putting friendship aside, what interested you about his work?

SM: When I first saw the elderly gentleman with the beard “in action” in 2000, working with clay at a ceramics symposium in Kalinovo, how he sovereignly modelled with generosity, how he hardly rested, I didn’t know who he was yet. He definitely “got me” with his monumental expression of material processing and absolute commitment to art. Uncompromising. I consider his work to be timeless and I see its value in a broader than Czechoslovak, local context.

Photo: Hynek Alt.

Photo: archive of SM, 2013.

Academic sculptor Imrich Vanek (1931 – 2015) was born on 20 March 1931 in Nové Zámky. He studied at the Academy of Applied Arts in Prague under prof. Otto Eckert (1956 – 1962). He was engaged in chamber ceramic sculpture and is the author of several design proposals and numerous sculptural works in architecture: a relief for the Krym Hotel in Bratislava (1964), a relief in the House of Mourning in Nové Zámky (1971), a relief for the building of the CSA Travel Agency in Košice (1975), a relief in the Istropolis House of Trade Unions in Bratislava (1980). His work has been awarded many times and is part of collections at home and abroad.

See also:

View of the house from the street