Essay / EVERYONE LIKES A GOOD STORY

Filipe Magalhães telling a story of the collective rebirth of architecture

Once upon a time, in a city far in the east, a distinguished architect won a competition for a new synagogue. Some say that, despite such honor, the prestigious figure never visited the building site, nor the completed piece. Naturally, such a memoir contributes to the mystification of the building, the protagonist of this story.

(Taken from a more pragmatic point of view, we could say that Peter Behrens had more important things to worry about in 1928. Nevertheless, we are not interested in this version since pragmatism is the enemy of a good romance.)

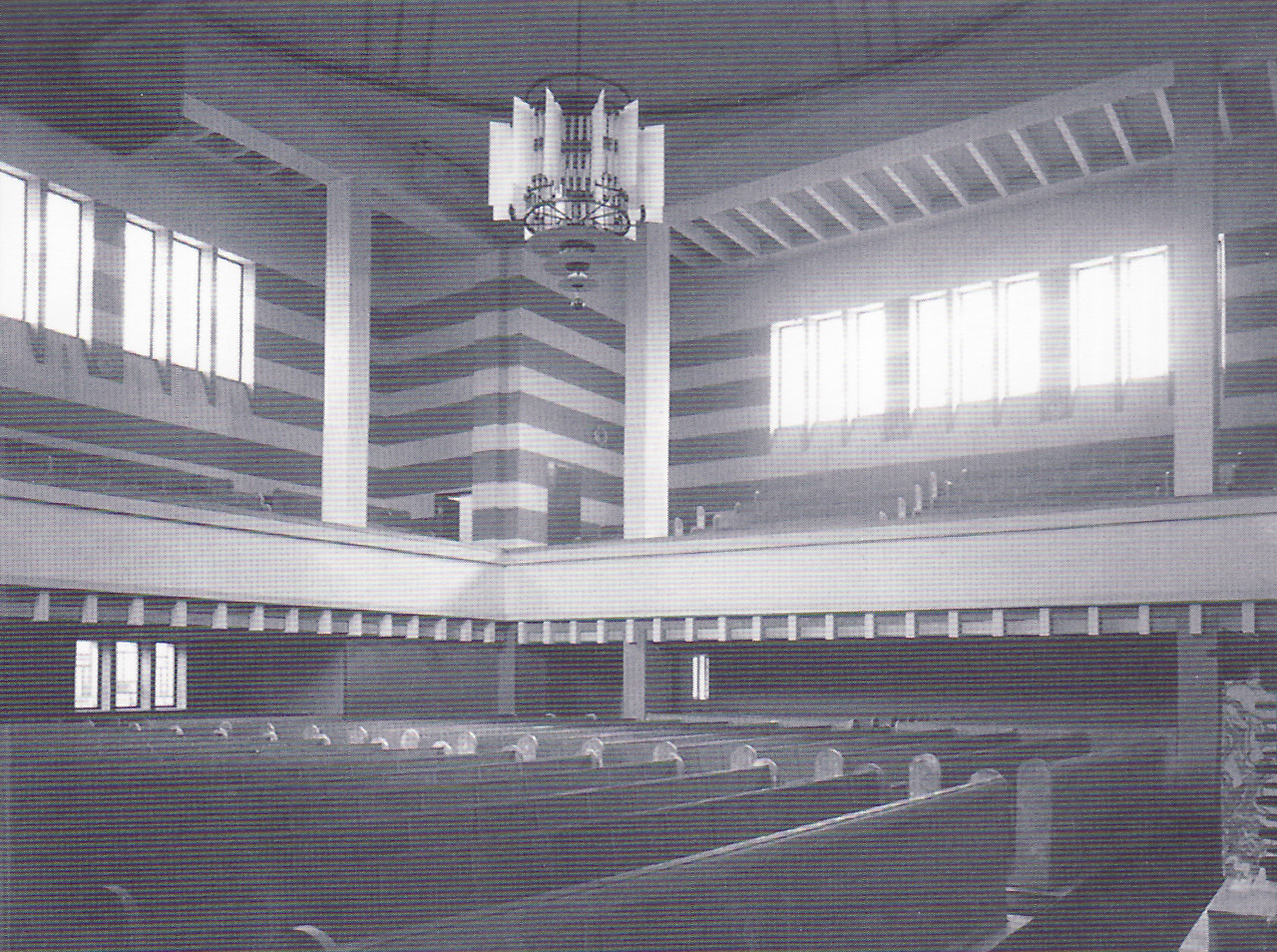

1928, photo: author unknown

Some could say that the building was just a big container, a glorified ornamented box. Destined for a religious cult, a lot could be supposed about its original architecture, about the way it related to the city, about its witty materiality, however that is not the point of this narrative. What truly matters is that the building was a synagogue for only a decade, falling into an (elastic) existential innuendo.

In a surprising turn of events, in 1941, the beautiful big box was forcibly taken by evil anti-heroes and was converted into a grain silo. No more cult, and the function became irrelevant, the tyrants assumed. (Ironically, one could argue in favor of such a rational decision, considering the qualities of the big room, and the impression the building gave as a type; yet, for the sake of the narrative, we’ll consider this moment as the first of many defeats of our hero.)

Just a few years later, after the end of the big war, the grain was taken away and the building became a concert hall with little or no relation to its spatial qualities. What could have been an anticipated victory became yet another sad downfall.

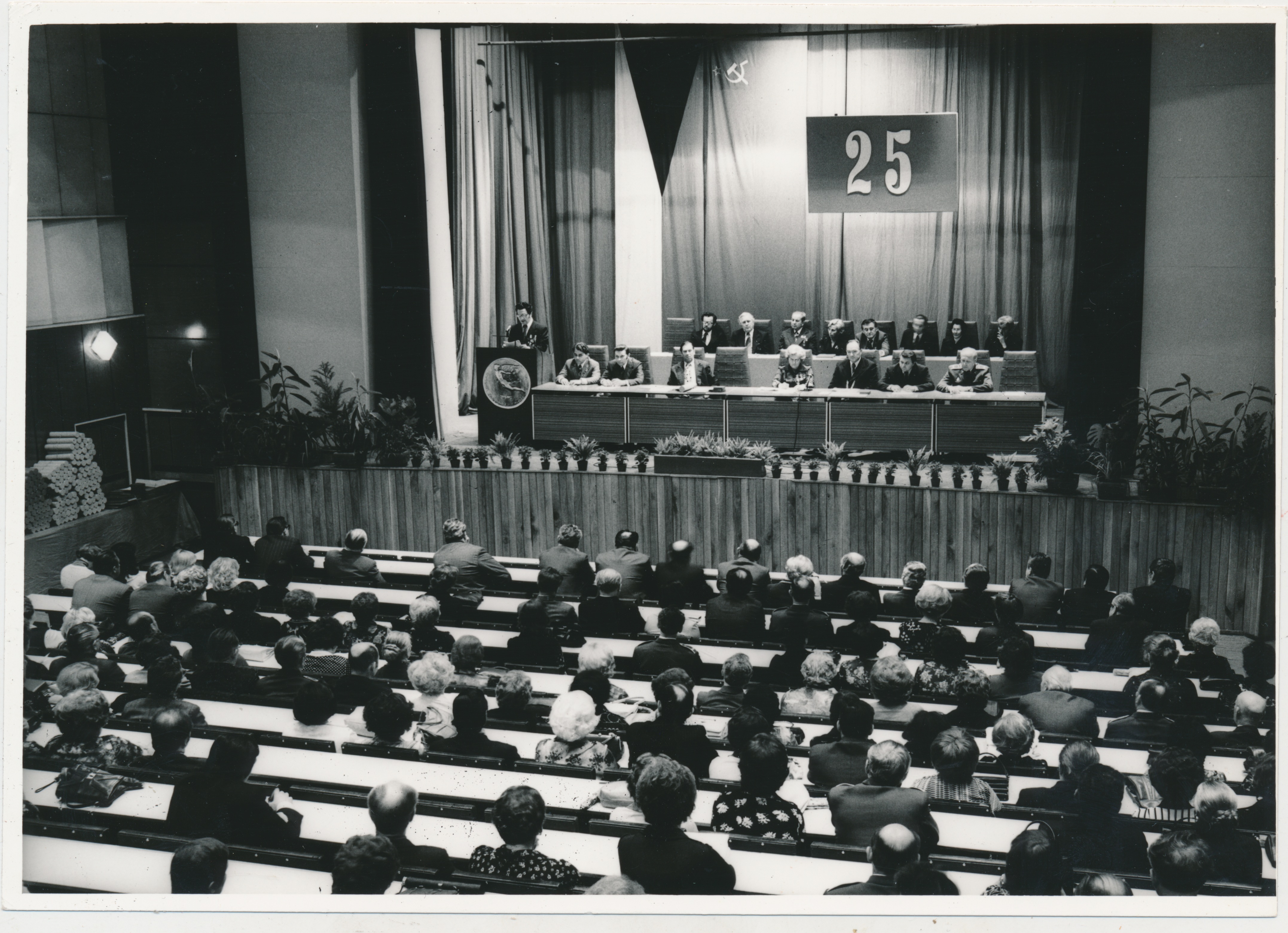

Some time after, in a sumptuous move with a clear lack of imagination, the concert hall became an auditorium for a local university. Once more, the qualities that made our hero extraordinary remained hidden, like a galleon at the bottom of the sea.

The building was returned to the Jewish community half a century after having been taken away. However, the number of users had gradually decreased to the point where its original purpose was lost. The city had expanded towards the west, and not even the use as a cinema lasted long, with the malevolent shopping malls providing the final blow to the forcibly flexible structure.

After such long battles, our hero rested and this could have been one of those stories where the good guys lose.

1978, photo: author unknown

It is undeniable that the several misuses of the synagogue weakened it: what was planned to be a proud public forum had its essence altered, even removed, since the public didn’t find its space in it anymore. If anything, there was now only a ruin of glorious dimensions.

But the story was not meant to end like this and, to semi-quote Jeffrey Goldblum, “architecture found a way”. Not through the miraculous perks of modern technology, cheap rhetoric or sci-fi images. Not through the usual political actors and their political agendas with public budgets. Not through the wonders of profit-driven private investment. Not because a princess kissed a frog.

The building won because its architecture qualities were outstanding and have not disappeared: they were just hiding behind the curtain, waiting. Despite all the severe interventions, changes of use and general condescension, the original space that Behrens envisioned was there and a group of actors knew about it.

The story of the rebirth of the forum is one of intelligence and dedication. Architects like to design – nothing new there –, but before being designers they are thinkers. They put themselves on the line for what they produce physically, but mostly intellectually; an architecture project is, before anything else, a mental construction.

In close relation with the local community that wanted to, without money, bring the forum back, Plural, the paladins of this narrative, were asked to help by bringing a certain expertise to the discussion, and maybe be part of the design. But what can an architect do without money? Aren’t all architects playboys of third party’s budgets? And even worse: how can an architect work in such close relation to a community? Isn’t that the kind of propaganda architects like to talk about, but run away from?

2013, photo: Marek Jančúch

2014, photo: Dalibor Adamus

In what proved to be the most intelligent move, Plural proposed to add nothing else. This would be a project of removal and, by doing that, they would bring the program in and open the forum again. The apparently anticlimactic proposal became the backbone of everything that followed.

The intervention took several years, and was done with care. It had several phases, stages, moments, and revealed the forum since the start, allowing the public to engage with the building even before it was reconditioned. If the project would have to stop during the process, it had already won. Every removed wall showed a new perspective; every floor became a stage.

The construction was supported by an endless amount of small private donations, a bit of faith and a big amount of intelligence. Patience also played a key role.

The architects limited themselves to the restoration of key surfaces, the addition of multifunctional small-scale infrastructure, and white paint. They relied on an idea, without being idealists. They collaborated with the architect that never showed up, without him knowing about it. They finished the work Behrens started, making it better.

Some people say “a secret to a happy life are low expectations”. Not anymore.

2018, photo: Katherine Thude

The discussion is not about ecology, European identity or sustainability; it is not a contemporary discussion. It is also not about history or progress. It refers to use, perception and illusion. It proves architecture to be a discipline of profound intelligence when rightly mastered.

In a time of polarizing “eithers/ors”, the Synagogue seems to be standing proudly in a “both/and” condition.

2018, photo: Filipe Magalhães