Hidden Cities / LEARNING A CITY

How do we learn cities? What is not written anywhere. Not new routes or secret clubs, but the city and our bodies in it. Its rhythm, its movements, gestures, subtle rules.

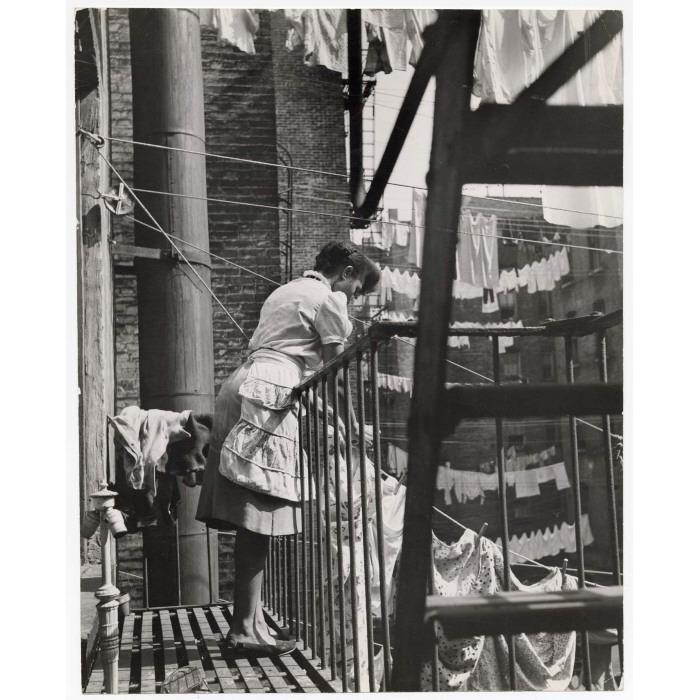

Gordon Parks, a young woman on a fire escape, hanging laundry on lines stretched between Harlem houses, 1948, source: kvetchlandia.tumblr.com

Learning New York: its fast pace, the fact that only tourists wait at red lights and the subway can change routes at any time, that the water boils faster, that I should ask for a small coffee only to get a much bigger one than I want anyway, and when finish my meal in a restaurant, the bill lands on the table because time here is vertical, time here is vertigo, and every minute is worth as much as a square meter. That time and space here is a dense, electrifying mass, that the shallow recesses in the subway tunnel are for the janitors to crawl into when a train whizzes right by their bodies, that the elevator doors sometimes open right into the apartment. Learning the city means learning new hand routes: locking and unlocking in reverse, swiping the metro card properly through the turnstile (neither too slow nor too fast). To raise the right hand at a certain angle to stop a taxi.

Learning that if I put on wet clothes during a heatwave, they will dry on me by the time I walk to the subway station.

Getting to know a city, like anything else, can’t be rushed. It reveals itself in time, in changing light. To truly know the city, like to know the other, is only possible if we are with it: happy, hungry, tired, sad, frustrated, angry, lazy, drunk, curious.

I was reminded of my favorite essay by Georges Perec, The Infra-Ordinary.

“We sleep through life as in a waking dream. But where is our life? Where is our body? Where is our space? How do we talk about these ‘ordinary things,’ how do we recognize them-recognize them, not flush them away, but pluck them out of the debris in which they remain wedged, give them meaning, language, let them, finally, speak of what they are, of what we are.

Perhaps we need to finally find our own anthropology, one that speaks about us, that searches within us for what we have so long acquired by plundering others. No longer the exotic, but the endotic.

To question things that seem so obvious that we have forgotten their origins[1].

Brooklyn, summer 2016. I’m renting a room in Lefferts Gardens, in a four-story house that’s about a century old. I watch the sweetish smoke of marijuana wafting lazily up the dingy staircase, watch the ordered bone of a chicken lying in baroque gloom on the mezzanine floor, which no one will pick up for a week. Gradually I learn the street and its sounds. The rap from the big cars rumbles through the street every day, Jay-Z vibrates the glass on the windows. Jay-Z, like Brooklyn’s J and Z subway lines.

The sirens of police cars and ambulances distort like a fatamorgana in the hot air radiating off the concrete. For one whole week, the water hydrant is open until its tank is drained. I can’t sleep because of its throbbing sound.

The best thing in the Lefferts Avenue apartment is the fire escape outside my room window. I’ve dreamed of a fire escape for a long time, especially after seeing the movie Frances Ha. It’s summer, so I sit on it almost all the time – with a book, with coffee, with a glass of rosé on the rocks. In a delirious heatwave, I observe street life and its rituals, because every street has its rituals. After a few days, I observe that the gentleman from the house across the street goes to get his newspaper every morning, at half past nine sharp.

I love doing laundry, and New York offers a new experience, an extension of the domestic ritual: most apartments don’t have washing machines, so I spend my time in laundromats, which are a kind of litmus test of neighbourhood life. I always go with a book and enjoy the wait. I choose the washing machine by number (I try to grab 22 or 29) and then I just sit, read, observe what’s going on around me, and stare at the spinning drum.

The dryer is one thing I don’t like.

In the summer of 2016, under new circumstances, I decide to dry laundry “al fresco” on my fire escape “balcony”. I’ll get some pins and twine from the store, which I’ll thoughtfully stretch in several rows across the metal structure. Earlier in the day, I lug home a heavy plastic bag full of wet stuff to hang my clothes on the fire ladder. The sun burns fiercely, the laundry smells. I solemnly crack open a beer – contentment and a strange sense of home washes over me.

Forgetting the city, or endotic to exotic

How do we forget cities? How quickly does a city forget itself, its rituals? Memory survives in great events. Brooklyn Bridge 1869, the Twin Towers 2001, Wall Street 2008, Chelsea Hotel 2011. Great successes and great failures, an official biography stripped of everything between the lines, of lost noise. Everything else disappears if its traces don’t survive in literature: the unrequited glances, the side-street conversations, the stories from the bars after the final one. Our own anthropology, as Perec said.

“Tidal waves, volcanic eruptions, tower blocks that collapse, forest fires, tunnels that cave in, the Drugstore de Champs-Elysées burns down. Awful! Terrible! Monstrous! Scandalous! (…) What’s really going on, what we’re experiencing, the rest, all the rest, where is it? How should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day and recurs everyday: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual?”[2]

Infra-ordinary, as such laundry. Drying laundry is the breath of the city, it externalizes its life, its rhythm, its intimacy. Laundry in the streets, like the tide, a primordial rhythm that is not subject to anything but the weather.

How did New Yorkers dry it, before they started looking into giant, hypnotic dryers? They seem to have forgotten all about their European laundry, the clotheslines strung across the streets of the Lower East Side.

When I type “immigrants-in-new-york-laundry” into Google, this photo, among others, pops up:

Monday laundry in New York in the early years of the 20th century, when there were hundreds of thousands of Italians who arrived every year to the United States. In 1920, there were more than 1,600,000 residents of the United States born in Italy. Tenements at Park Avenue and 107th Street, New York City, circa 1898–1910, source: wikipedia.org

A few hours later, while my laundry hangs out in the hot summer breeze, I’m working in my room sitting at my desk. Suddenly, I pick up a sound that breaks out of the familiar sonic routine. The street is filled with the sound of women’s laughter, and when it doesn’t stop after a while, I lean out of the window to see two women on the street taking pictures of something on their phones and laughing terribly, shaking themselves and their handbags, hairstyles and necklaces, choking with laughter, as if they’ve seen the funniest thing in the world.

“Oh my God look at that, that is so craaaaaaazyyyyyy!”, one of them shouts, while the other one starts coughing loudly with laughter.

I look out onto the street, but I don’t see any spectacle.

I’m really curious what’s so crazy.

After a while it dawns on me: my drying laundry.

Photo: author’s archive.

1 Georges Perec, The Infra-Ordinary (1973)

2 Georges Perec, The Infra-Ordinary (1973)