Confrontations / CITY_MYTH

The individual texts of the series consist of a juxtaposition of words - City, Myth, Modernity, Pool. The mutual confrontation of pairs of words is not about confirming unambiguous relations, a harmonious whole, but about searching for possible disagreements. The confrontation narrows the wide range of their individual meanings.

In the 20th century Bratislava found itself in several ideologically different political systems. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy, the first Czech-Slovak Republic, the Slovak State, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, the Slovak Republic. Its history is therefore rather discontinuous. In each of these state situations, Bratislava had a slightly different status, administrative and economic background, and it formed a different official social hierarchy. At the same time, the frequency with which exchanges occurred explains the state of the urban space.

” ‘…provisionality in provisionality, temporality in temporality’, which brings a special vitality to urban space.”[1]

Bratislava is not strictly rastered as Barcelona or Manhattan. Rather, Bratislava is a collage of fragments of projects emerging over a longer time span. The aforementioned ideological and power (administrative) turbulences are certainly one of the factors behind the emergence of this situation. But not the only one. This, or a very similar situation, occurred for many other European cities during the 20th century.

Hrbáň and Vasičák, in their text Prenatálna metropola, describe Bratislava as a fragmented, sparse and provisional city. “The urban stratification of Bratislava is uneven. It reflects economic possibilities, a certain charm of primordiality and the speed with which it can always occupy new territories. It is made up of fragments of neighbourhoods, street breaks and empty gaps.”[2]

The city is strongly determined topographically by two natural phenomena – the Danube and the massif of the Little Carpathians, which is also reflected charateristically in the urban structure. However, it is not limited by them. Its urbanisation is taking place from the city further out, expanding it continuously, occupying new territories. Yet the city itself, though close to the historic centre, is not densely built up at all.

Modernist urban development is characterised by its abruptness, its totality. In our country, it clashed with the period of the fascist and then communist regimes. Especially during the forty years of communism, the greatest expansion into the surrounding area took place in Bratislava. A planned urbanism of grand gestures that happened too quickly for the scale of the intervention. From these ambitious projects came diluted fragments of what these territories were meant to be. Many empty places were created.

The socialist expansion then left out the industrial, warehouse, gardening areas, which gradually lost their justification and became areas of nothing and nobody. Apart from the current large developments, many of these empty places in Bratislava are still filled provisionally – with parking lots, kiosks, advertising spaces, various other ephemeral typologies, or they are used by gas stations, shopping centers,… On the one hand, these typologies are essentially the emergence of the periphery in immediate contact with the centre, in the inner city. On the other hand, these typologies do not contribute to a higher density of development in the centre, as would be expected.

“Today’s Bratislava is administratively five times larger, but with a lower population density than in 1945.”[3]

Bratislava does not at all correspond to the modernist ideals of the city as an integrated and stratified agglomeration. It is a heterogeneous system of parts.

“What emerges is a sparse network that does not capture, concentrate, or concentrates only sporadically and locally. Micro-densities of buildings, programs, and urban situations are created, spilling out across the city.”[4]

Koolhaas has called these places “active points of urban intensity” that exude a sense of urbanity that, if unattended to, will quickly weaken.[5] It can weaken when the system is overstretched, which is assumed to be able to expand indefinitely. It can very quickly become diluted, as is the case in Bratislava.

With a sparse built-up area such as Bratislava, there are also higher demands on mobility. Bratislava is a city with organised movement, with main radials and ring roads. Compared to more traditional focal points in the form of empty places in a dense structure such as squares, streets, boulevards, Bratislava is characterized, with the exception of the historic centre, by densification in public transport terminals, traffic junctions, bus stops,… The most common way of perceiving Bratislava is the process of moving through the city.

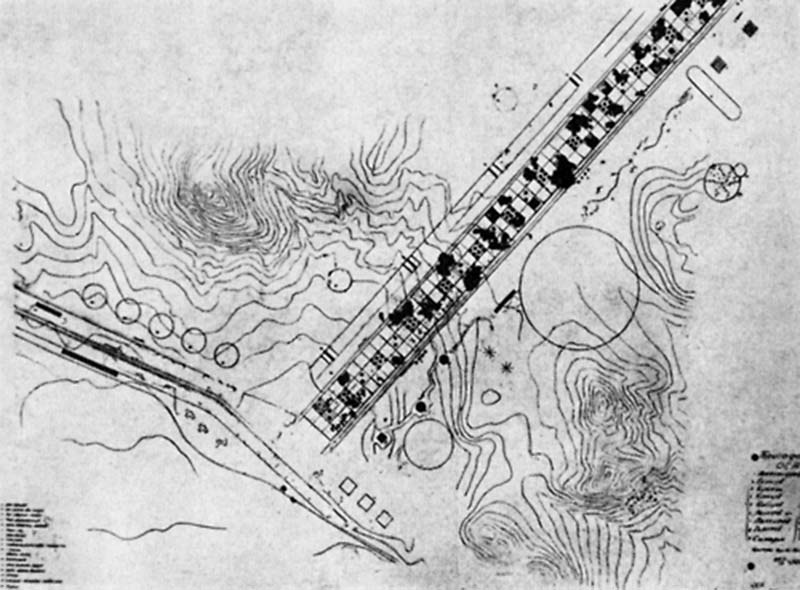

Design of a linear city in the framework of an urban design competition for the chemical and metallurgical headquarters of Magnitogorsk, 1930, Ivan Leonidov (Russian group of architects OSA), source: socks-studio.com

The hyperbole of excitement about the possibilities of transport were the Russian desurbanists who declared death to the city in the 1930s. “The city must perish… The revolution in transportation and the automobileization of entire territories fundamentally changes the established view of the necessity of densification and clustering of buildings and dwellings.”[6] Ochitovič’s desurbanist vision of the city consisted of separate cells transported by the highway network and occupying arbitrary locations. A loose scattering of dwellings in a landscape connected by lines of roads.

In Russia at the time, the desurbanists were concerned with defining themselves against the previous vertical hierarchical society of a centralized approach to the city. The complete homogenization and horizontalization of human dwellings proved unworkable. With such an approach, important centralities – active points of urban intensity, places of concentration of inhabitants and their confrontation – completely disappear. Desurbanist ideas are the complete abolition of an important tension generating further development.

Bratislava, with its vastness and linearity, in some ways resembles desurban ideals. This situation was created mainly in the socialist period (1960s-1990s) by the construction of housing estates, which form its largest part. The housing estates were often located on the basis of technocratic parameters, connected to the original city structure via main traffic radials, without any consistent contextual connection and intermingling. Moreover, many of these projects have been only partially implemented. Substantial housing has been built, with no time or resources left for the remaining facilities. “And so these housing estates, while forming today disjointed fragments of the city, are themselves only fragments.”[7]

Every new development since the 1990s has become dependent on infrastructure that has not had the means to be completed. New developments have opportunistically sought to occupy valuable sites of existing infrastructure, creating a new layer. This new architecturally heterogeneous urban development was thus, paradoxically, determined by outdated urban plans whose concept was rather homogenization.

With some exceptions, the current redevelopment and development of the original industrial sites does not deviate from the existing street system at all. Changes occur within blocks, at the scale of individual houses. Bratislava lacks a more comprehensive formal plan, resulting in its outward formal irregularity and heterogeneity.

“….: a street seems to have two street lines and repeatedly changes from a wide boulevard to a relatively narrow street, while also randomly changing its height – from ground floor to eight-storey houses. The impression here is that both the generally agreed-upon urban regulation and its violation enjoy equal weight.”[8]

Bratislava lacks a more comprehensive order; it is a system of fragments, ruins of projects. This quality can be dealt with primarily by intervening in the foci of urbanity, by condensing their intensity. Interventions in these points mean interventions in public spaces.