Confrontations / POOL_MYTH

The individual texts of the series consist of a juxtaposition of words - City, Myth, Modernity, Pool. The mutual confrontation of pairs of words is not about confirming unambiguous relations, a harmonious whole, but about searching for possible disagreements. The confrontation narrows the wide range of their individual meanings.

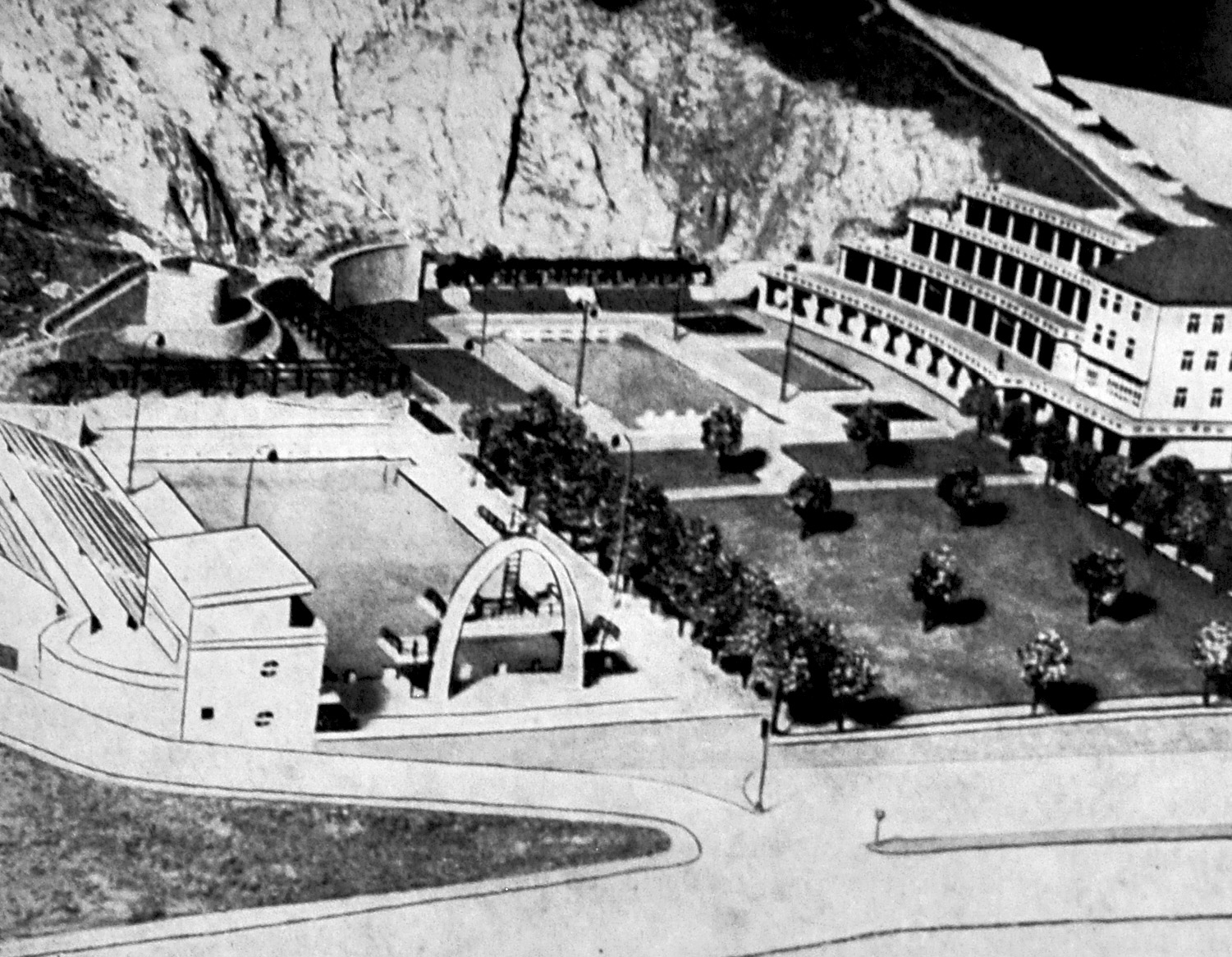

Project of the new summer swimming pool in the quarry under the Castle Hill, source: Bratislava/ Pressburg. Bratislava: the State Printing House, 1943.

An example of a mythical form, a modernist ruin, is the swimming pool – a public swimming pool in the quarry under the Castle Hill, a project of the 1940s, which was never completed despite all the turbulent changes of that period and the ideological changes of the state apparatuses, due to technical difficulties. It became a ruin, an ideal material for later reinterpretations of the situation, a weave of urban myths, a niche for reflection on the times. Several times ideologically appropriated, several times emptied and refilled.

The land on which the pool stands is located on Žižkova Street, adjacent to today’s Nicolaus’s and Jewish cemeteries on one side, and on the other side it came into contact with the new development of Zuckermandel, the Steep Road, a street connecting the area under the Castle Hill with Castle Hill and the tram tunnel. Geologically, it is located at the foot of the south-western slope of the Little Carpathians, at the point where they dip into the Danubian lowland, in close proximity to the Danube.

At the beginning of the 1940s, the Bratislava City Council, on the basis of the deficit of this kind of infrastructure, decided to build a public swimming pool under the Castle Hill, which was to be a modern, ecological and economical building.

Due to its location, the swimming pool was technologically based on the possibility of drawing water directly from the Danube, which was then to be pumped to the castle rock. From there it would flow down the quarry walls, during which it would be heated by the sun’s rays. In the course of construction, the basements of the previous buildings or some tunnels were found to have disappeared, which is probably why the project was modified in the late 1940s and the original 5 m depth of the pool was adjusted to 2.5 m.

Neither this incident nor the subsequent solution to the problem was documented and described in any detail at the time. Whether the tunnels that were encountered were backfilled or the stabilization of the foundations was solved in another way. Later, after the redesign, the decision was taken to stop construction. Further construction did not resume until 1952, when the Stavokombinát [Construction Department] drew up new designs for the swimming pool, whose capacity was to be increased to 2,500 visitors a day, and added other amenities.

Construction was again suspended until 1968, when a trial filling with water was started. Water was drawn from the Danube, but this original plan was abandoned. One of the reasons was that the pumping verification tests during the 1960s showed that the borehole’s yield was only able to cover consumption during the spring months. At the same time, excessive water leakage was detected during test pumping. At that time, the entire volume of the pool drained within three days. On the one hand, the pool itself was obviously poorly constructed; on the other hand, the structure of the Little Carpathians in that area is generally very tectonically disturbed, cracked and, moreover, uneven.

In the end, the pool was never intended for bathing or handed over to the public. The town searched for a new use for the pool for some time, several different proposals were drawn up, but the recreational function was always preserved in all of them. According to the mayor of the Old Town, the investors who were interested in the area always disappeared after a while[1].

Despite the fact that the pool has never functioned, apart from a test fill, many people claim to have swum in it. It represents a special form of irrational collective memory. It was never handed over to the public as a public swimming pool, but it fulfilled its function (in the city). On the basis of the contextual holes in the rational arguments, there was room for the insertion of meanings, new interpretations. Myths strive for a consistent interpretation, a coherent causal sequence. Explanation of every detail.

Viliam Klimáček, in his book Naďa má čas [Naďa has time], has revealed the true nature of this place and what activities are concealed here. The swimming pool with a series of spiral tunnels, placed in several layers on top of each other, carved in the castle rock below the pool and the large tram tunnel are a “time tunnel”. The matter of the time machine was water.

Here, as if to legitimize the choice of the site for the pool, which from a rational geological point of view is challenged by the unsuitability of the bedrock. Consequently, the ability of the borehole to actually supply the pool in the summer months is called into question. The technical deficiencies become the intention. The ultimate failure is perhaps just a moment of self-reflection, or an inability to wield too much power.

The pool in a state of ruin became a form for inscribing meanings. At the same time, as a form/ruin, it has become a carrier of continuity. It represents the maturing and structurally excited period of the building of the modern Slovak state in the form of an ambitious project in the spirit of modernist ideals. Due to various obstacles, the project could not be completed at that time. Its construction was to be resumed in the 1950s under the new regime. Here it appears as a residue of Nazi ambitions. Communism came up with a new project increasing the capacity of the original pool and a new contractor. Construction was put on hold until the sixties, when a trial filling was to take place. It failed.

Current situation, source: mpba.sk.