Interview / KAROL PICHLER

ĽH: How many languages do you know?

KP: Each of the languages that knows me, also determines my range of movement and action:

German brings me close to my favorites – Elfride Jelinek, Gabriele Petricek or Heinrich von Kleist at an intimate distance of 30 cm.

French allows me to move in the arabesque labyrinths of the French (linguistic) park.

Portuguese can transport me across the Atlantic to my native Rio de Janeiro.

English is a good servant for me to navigate and move through all four cardinal directions.

Italian, it just lets me integrate myself into the universes of Domus or VOGUE Italia magazines.

Hungarian now only accompanies me occasionally, 400 km there and back, during visits to the Gellért Spa.

From where and what family do you come from?

I was born in three cities: in Bratislava, in Pressburg and Pozsonyban. And it is this cosmopolitan situation as if it determined the prescription of the axis and trajectory of my vital movement – my permanent nomadism. I come from a family that had built around itself a kind of isolated protective microcosm, ensuring an inner freedom, so incompatible with the ideology manifested in the exterior and submerging the then everyday life in leaden greyness. This protective shell was built by my grandparents and they managed to pass the baton to me with the message that the world is about something else and is built on different values than the current ruling political power tries to impose on us.

Especially my grandfathers instilled in me how important it is to seek out rather visionary horizons, full of colourful adventures, and thus escape the negative radiation of the bastardised regime. And they themselves – Little Grandpa and Grossvater Pichler were both great adventurers. The former first had to travel halfway around the world – all the way from Asia to Japan, and then, in the manner of the heroes of Hesse’s novels (not reconciled to the world), he returned to Bratislava and, at the age of over 40, started a family, built a house and planted a tree. My little grandmother was an activist and a member of all the emancipatory women’s associations of the time; her household boasted one of the first vacuum cleaners in Bratislava. During World War II, she fled into a mental adventure from which she was never able to return among us. Grossvater Pichler, in turn, adventurously escaped with his son from an internment camp when the German-speaking part of Bratislava’s population (not only those affiliated with fascism) was expelled after the war – he did not return to Vienna and stayed in Bratislava. My parents also led a somewhat adventurous lifestyle: my mother an archaeologist and my father a cultural officer, although nothing adventurous, they managed to arrange, without any commitment to the regime of the time, that we could have adventures every year in the 1970s, e.g. to travel to “the West”. So even as a junior I had already seen Gaudi’s palaces, Rembrandt’s Night Watch, the Art Brut collection in Lausanne, the Acropolis and Hagia Sophia.

What do you feel shaped you the most in your childhood? Can you think of specific people or experiences?

Looking in my rear view mirror, the following image appears. I grew up in a culturally rich background, representing for me, at the time, unknowingly, a firmly constructed support system of positive values on all platforms. I moved in a domestic environment, among Baroque furniture, combined with minimalist furniture from Krásna jizba, on the table were Čalovek’s cutlery, Taraba’s glassware, Moser, as well as solitary pieces of our cubism or art deco.

In terms of design, I would highlight only three or so illustrative experiences, pre-shaping my interest in the “pretty object”. In this way, they actually influenced the beginning of the future designer’s life path. I can still feel their colourful shadow over me even now:

Experience 1. When I was about thirteen years old, I discovered the Taccia lamp by the Castiglioni brothers in a Schöner Wohnen magazine (which I had to clip out every month at the foreign press shop). Its timeless elegance and unprecedentedly generous morphology have left me, to this day, utterly captivated and enchanted. It was and is something extraordinary – the French have a more appropriate term for it – “extraordinaire”. It was this lamp which “enlightened” me and showed me that even an ordinary object of everyday use can look “different”, carry constants with a different social-aesthetic surplus value of form and at the same time respect its function. It was probably already then that I realised what energy an object can convey through its shape for everyday (social) space.

Lamp Taccia. Achille & Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, 1962.

Experience 2. I also owe another discovery and experience to the “foreign press”. The fascination with the spatial creations of Joe Colombo and Verner Panton, their driving factor in the relation of colour and space. The futuristic vision of the dwelling of the one(Vision 1), as well as the already inhabited chromatic spaces of the other, have permanently imprinted a mark on my conscious and subconscious mind. They have shown me that chromatodysopsia can be cured and that grey, while essentially an elegant colour quality, is not for everyday social space.

Visiona 1 show (Wohnmodell) for Bayer AG, Joe Colombo, 1969.

Experience 3. At the turn of the 1970s, the House of Furniture on Štefánikova Street somehow miraculously sold foam sofas by Olivier Mourgue (we know him from Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey). I would occasionally make a pilgrimage there after school for pleasure, and, as I was usually alone in the shop, also revel in the ephemeral physical pleasure of its chaise longue.

Djinn Chaise Longue, Olivier Mourgue, 1965.

All such encounters of the “third kind” have contributed to the fact that my perception of the surrounding reality has completely changed – or rather, they have provoked my ignorance of it and have moved me into another, visionary “reality”, into other worlds, full of exciting “colourful” impulses.

Why did you study in Budapest and what did you study? You were already 23 when you started there. What did you do before that? How was the environment different from Bratislava?

I went to the then University of Arts and Crafts, now MOME Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, to study fine arts when I learned that there was such a possibility of studying at a school other than the Academy of Fine Arts and Design. The only affiliated quota department was the Tapestry Department, which made me extra happy. At a school focused on design, it was the only department exceptionally oriented towards art. The school was characterized by its focus on addressing specialized and professionally creative activities, in other words – it provided the opportunity to use the whole range of colors and not just “red” as it was at the then AFAD in Bratislava.

Who was the best teacher?

Mária Nemčeková Chmeliarová at the School of Applied Arts in Bratislava with her charismatic asceticism: she was able to instil in her students a hard creative discipline valid for life. In addition, I respect her for her authorship of the most remarkable Slovak author’s tapestry. At university it was Margit Szilvitzky who encouraged and supported my creative experiments and activities.

What was life like in Budapest? What about the art (or design) scene back then in Hungary? Did it surprise you in anything?

To study, to live in Budapest in the late 70s and 80s was to find oneself in an extraordinary situation – to be at the centre of a well-camouflaged subversive dynamic. Budapest formed an oxygene bubble for the rest of the Eastern socialist bloc of Europe. People went there to treat their souls as if to a spa, on pilgrimages for culture, and held underground “crusades” to rock concerts. We, living there at the time, were able to take full advantage of it, to enjoy this privilege in the full breadth of delicacies on offer: world film distribution, as well as film clubs with narrowly specific programming, imported foreign exhibitions, literature in translation or in the original foreign language, as well as Hungarian editions devoted to sociology, psychology, aesthetics, art, and, and, and.

And just as even today we don’t know much about the current Hungarian design scene, so too, during the period of my studies, not much was known about Hungarian design in the world. The school was well specialised, progressive, but in practice there was then this strange fusion between design, free art and artistic craft – which resulted in a hybrid position of the object, and such a resultant could not be properly placed in any of the above categories.

Where did you have your first exhibition? And what was it?

I had my first exhibition when I was still a college student at our cultural centre in Budapest. Only when the apparatchiks at the opening saw what kind of exhibition I had prepared, they immediately closed it for “technical reasons”. Thematically, I presented two phenomena – line and colour – from which the whole exhibition was deduced: objects and installations, photographs, an author’s book and a film (video did not yet exist). Perhaps the most provocative was the installation “What would our world look like without colour” – a black living space, an open cube on a scale of 1:1. However, before this exhibition I had already made several in-situ installations on the school campus as well as in public spaces in Budapest.

You came on board when postmodernism was already fully occupying the discourse in art and design (although more cautiously here). At the same time, society was also changing. Perestroika had set in. How did you perceive it?

Upon my return, compared to the lived time in Budapest, the local release still seemed like a rather harsh regime. To illustrate this, I would like to mention one small episode, now amusing, which I only learned about after the fall of the communist regime: when I started teaching at the School of Applied Arts, there was a committee at the Ministry of Education that dealt with the problem of whether or not a male teacher could wear a ponytail – because at that time I had long hair. In the end they left the matter unresolved and open, because I came from Budapest…

Which personalities, works of art, architecture or culture were formative for you at that time?

I considered the most powerful works of art, and this is true to this day, to be the two large canvases. The first one is called Persona by Ingmar Bergman and the second one is L’année dernière à Marienbad by Alain Resnais.

Who was close to your heart? And how did you perceive the previous generation (Vilhan, Milučký, etc.) ?

I used to follow the work in the “Western” world; I considered what was going on around me as a kind of limited, colourless necessity and boring commonplace, but I was always delighted when I discovered a work that broke out of this grey. I remember being quite contemptuous of our architecture and culture at the time; I categorized Milučký’s crematorium as déjà vu. I was also not, and am not now with hindsight, a fan of the “tubular” decorative style of the 1980s in our interior architecture.

Where did you go in the city?

Budapest HQ was in Szép Ilonka near the school – a forgotten pavilion from the 60s, or in the city the Gerbaud and Russwurm cafes. In Bratislava it was – for some Depresso, for others Airplane – but it was still the same “institution” on the former Jiráskova Street, directly opposite the entrance to the Academy of Performing Arts, where I used to go for coffee after lunch; this often extended into an afternoon aperitif, loosely continued into evening of friendly discussions over rather bad wine, and ending with the last fernet, how many times after the closing…

Your material/media was and is mainly textiles, but your scope is much wider. But let’s go to textiles. You work with it quite comprehensively. Both as a designer and as a freelance artist. And you know a lot about the techniques of its production and processing. How would you define your relationship to it? And what did it get you?

Textiles, it’s a love, but also my weakness! It is the only thing which opens spontaneously and devotedly to my hands, but it can also obey and carry out my rational commands. It can be a subtle pet, but also a fierce defiant partisan, protecting his position, whom I have to (of course tenderly) conquer by force. It is both bottom and top. It both hides and reveals virtues and vices in one character. it fascinates me with its chameleonic potential; it can (ex)change its substance, once it is flat/occupies only a surface – it is determined only by width and length, but it can easily take on a third dimension – depth – and sag into a spatial position. And it can flirt with the fourth dimension, time, without a care in the world. Its capacities are not yet sufficiently explored, it remains enigmatic and only gives a hint of its potential possibilities in response to the unknown – innovative technological developments and their integration as well. Our love, hopefully reciprocated, will not be constrained and will not stop growing wings.

Textiles is, of course, also fashion and the fashion world. You are part of it. Have you ever produced your conceptual garments in larger series? Or has it always been more of an original garment?

It’s always just been about an author’s approach. No two pieces are the same; you don’t wear the same (garment by) Pichler twice.

Did you sell in Dielo? Who were the clients/collectors? How would you briefly describe your style, principle, or ritual?

I only participated in one clothing and jewelry sales show at Dielo back in the 1980s. I sold one garment at the time and a fellow exhibitor bought that one as well. Selling my work, and not only in Dielo, has never interested me.

In design, my principle and credo is to give the user a base in a given object, so that, according to their own requirements on a social, mental and aesthetic level, they can complete the object, with a certain amount of their creativity. In this way I elevate the user of the object to the level of a kind of co-creator or co-author. The object, by its “incompleteness”, stands open, leaving a visionary space for its completion. Some only hint, others openly provoke the possible initiation of a manual finishing process and the leading to one of the possible resulting interpretative positions. Such a process is also true of many of my works in the liberal arts, where the process takes place on a more mental plane.

PROTEa-x substance, mutation variations.

Do you have a monumental piece?

Slovakia will be able to boast its first real tapestry. We can only call a tapestry a hand-woven tapestry that was made at La Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris. It is in its ateliers that my first monumental tapestry, the Mille Fleurs tapestry, is taking shape. Tapestry workshops are the highest professional institution in their field, and for every artist, especially for a “textile artist”, the weaving of his tapestry – in these former royal workshops with a tradition dating back to the Middle Ages – means the highest appreciation and recognition. As the tapestry manufactory is now under the administration of the Mobilier national, the projects produced remain the property of the French presidential office or other government institution. It is therefore a ‘monumental’ par excellence, in the true sense of the word. In 2017, I received an invitation from La Manufacture des Gobelins to create a design for a wall tapestry. I prepared the project, bringing an innovative position not only from an artistic point of view, but especially from a technological one, thus encouraging the workshops themselves to move into the 21st century. Although the tapestry will be woven in a classical way, it will be woven with the integration of optical fibre. The result will be a wall tapestry whose individual motifs will gradually light up in a certain choreographed dynamic until the whole surface is completely lit up in the resulting fireworks display.

Design for the Mille Fleurs tapestry for La Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris, the phase of full illumination of the motifs, photo: author.

Design for the Mille Fleurs tapestry for La Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris, phase of partial illumination of the motifs, photo: author.

How did you perceive fashion in Czechoslovakia at the end of the 80s? And how after the Velvet revolution? Who was interesting? And what irritated you?

Fashion in the Czechoslovakia didn’t interest me at all. With unconcealed mockery I categorised and named it as “memory – souvenir fashion”, as it brought with at least a two-year delay tendencies that had already been long gone in the world in the meantime, and it let “revive” the fashion that had already fallen into oblivion. Since the second half of the 1970s, I had enjoyed a subscription to the French VOGUE, which gave me the opportunity to follow world fashion from the “front row”. Bourdin’s or Newton’s fashion photo essays of the time remain unforgettable to this day!

A propos in connection with fashion: earlier I paid attention to texts by Antonín Kybal, for example, discussing the proportions of patterns on dresses, their formation of spatial relations, as well as their relation to the human body, the dynamics of their shapes and forms, or their chromatic values. In parallel, I was also fascinated by the study of (not only our) ethnographic archives.

Textile production in Slovakia changed quite a lot after the Velvet revolution. Let’s say straightforwardly, for the worse. What are you perhaps most sad about?

I had not built any bond, no special “emotional” attachment to our textile industry, so I am only sorry that our whole advanced textile industry – e.g. the patent of the unique jet loom – has dehumanizingly turned into a market with cheap labour and production force.

I know that you have worked and are working with the big fashion houses. What kind of collaborations are they? Do you go to fashion shows? Do you currently have a favourite fashion designer/s in the world? And have you noticed anyone in Slovakia?

Collaborations between fashion houses and artists are historically confirmed and frequent. Even Gabrielle Chanel herself had her tweeds designed by Russian artist-painters.

From the collection TWEEDS, photo: author.

From the collection TWEEDS, photo: author.

From the collection TWEEDS, photo: author.

Fashion designers in the classical sense of the word are almost non-existent today. They have been replaced by a new generation of creative businessmen, measuring the success of collections with profit ciphers. The second group is made up of the “DNA illustrators” of this or that fashion house. Their creative function consists of transcribing the results of “archaeological research” in the house’s archives into today’s visual language, thus ensuring the vital continuity of the fashion house. My “closely followed trains” remained only the work of Reia Kawakubo for her own label Comme des Garçons and Walter van Beirendonck. Kawakubo for her tireless innovative creativity, her philosophical approach to the human body as well as the materials she envelops it in. Van Beirendonck, the enfant terrible of men’s fashion, hides in humorous but artistically powerful hyperbole, the perfect garment architecture for the connoisseur. The creative Iris van Herpen and Hussein Chalayan could also fall into the category of interesting, but in their case the garments are unqualifiable for “real life” – in their models it is possible to walk the catwalk, but they do not allow the wearer any further physical activity, thus disqualifying themselves from the game and confining themselves to museum showcases.

Model Walter van Beirendonck, collection Spring 2016, photo: archive of Walter van Beirendonck.

Right after school you started teaching. Your students remember it as a pretty pivotal experience. They say you were very demanding, but at the same time extremely inspiring and opened up broad horizons for them.

A school should be a defined territory, more specifically a floor – most importantly, it should be sufficiently spatially (mentally and physically) generous. An exercise floor on which the teacher must teach the pupil to walk; he should already know how to walk. Teach him to walk uprightly, confidently, dynamically, not to stagger, but to walk straight and erect, without a hunched torso, without a bent back. Above all, he should step firmly as he strides, determining with his stride and its echo the dynamics of the space in which he is (just) moving. The step must be perceptible and perceived, and its solidity taken with self-evident ease. Only when the teacher hears his pupil walk away does he know that he has fulfilled his mission.

What was Bratislava like at the beginning of the 90s from your point of view and what is it like today?

Beauty on the Danube: after its serious disfigurement in the 60s and 70s, in the 90s it received only a kind of a replacement make-up, a cheap make-up of a Balkan flapper. I don’t know to what extent she is, but it doesn’t seem to me that today’s cosmetic surgery is so developed that it can bring the original beauty back to new life. As I observe, so far this former beauty is only getting small topical patches again. I haven’t yet seen any project that has elevated this city to a higher quality category. Bratislava is currently, and will continue to be, one big social archipelago. Just small ‘islands’, isolated from each other, with no functioning social space in between. These islands with their autonomous vitality and tribal social belonging remain without communication links and do not stand on any urban social carpet.

P. S. 1 – So far, none of the professionals active in architecture to whom I showed the Bratislava project by Zaha Hadid guessed that it was her project. (Personally, I think they pulled it out of the trash under her drawing board.) If one was commissioning a project from a renowned architect, one should probably have chosen a truly representative one, shining like a jewel, which would at the same time proudly bear the name of its creator, but not such a bland, anonymous one, which in other cities is more often found outside the city centre in terms of type. And even in Bratislava itself, the project has an older brother, not so tall in stature – on Bajkalská Street. Down town in this form would be appreciated on the opposite bank of the Danube, where it would create a suitable echo to the genius loci.

P. S. 2 – The tragedy and destruction of the original Old Town actually began with the inappropriate positioning of the Devín Hotel building in its urban context. After that it was just dominoes…

In your work there is an obvious postmodern and conceptual approach, but also the tradition of modernism (geometry, abstraction) – you like provocation, multiplication, systems, installation, spatial composition, play, collage. You work with textiles, but also with paper, plastic, photography, writing, food… You know how to be both minimalist and opulently narrative. This implies that you have no problem adapting yourself according to the project. What are you most interested in at the moment?

Nothing special and everything! I continue to captate the situations that surround me, to pass them through the filter of my prism and then return them to the exterior circulation again. The range of interest is very wide along both the horizontal and vertical axes, and the constant driving energy, downright motoric, remains an unflagging curiosity.

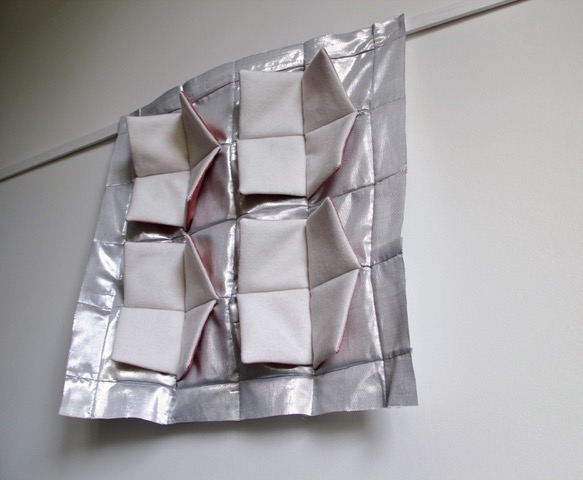

Part of the installation TIME-SQUARES – Present time, photo: author.

You travel a lot and have lived in several places around the world. Currently in Lyon. How has it changed you?

The nomadic way of life shows and gives a person especially the dimension of freedom. It is essentially an easier mountain climb on a kind of diachronic spiral, where each new turn reached opens up a different, unfamiliar perspective, but also a different angle and way of looking at the territories already left behind, already experienced. What excites me the most is to uncover spaces I have not yet explored…