Essay / INTRO

On the utopian concept in architecture

Intro

Architecture can create a (better) place to live. The range of ways in which it tries to do this is wide. From comfortable Loosian interiors, through functionalism to today’s user-optimised architecture. From the question of the quality of the covering of our everyday life to the production of exceptional experiences. More than the ways in which architecture improves our living conditions, I am primarily interested in the origins of this idea of improvement.

The Utopian Concept of Architecture as a Myth of Modernity

In the question of (finding, defining) a place where we should all be well, the notion of Utopia automatically comes to mind. Zygmund Bauman sketches the origins of Utopia against the backdrop of the disruptive, violent, uncertain world of the 16th century, when old customs and traditions were suddenly torn down. According to him, Utopia denotes the idea of an ordered, predictable, secure world, the idea of a good society[1].

Utopia, along with its architectural consequence in the concept of the Ideal City, is tied to the beginning of modern thought. Thus, I call the role of architecture to explicitly improve life/world/society the myth of modernity. A myth because, although this question seems natural and unquestionable nowadays, it nevertheless arose at a certain historical moment.

Roland Barthes explains myth through semiology, as a secondary system, a proposition whose function is to distort, to empty reality. What it deflates, empties is the original meaning (the primary system). In that case, the myth of architecture as a tool for building a better world was created by emptying the original meaning of architecture.[2] It would mean that architecture does not primarily serve for someone’s “good” as such, but has a different (original?) meaning.

Idea_Project

Barthes’s theory goes on to say that the fusion of empty meaning/form (architecture) and concept (the idea of a better world) into myth is not arbitrary, but motivated. That is, there are analogous aspects, i.e., equivalent properties of architecture and the idea of the good society on the basis of which this connection is possible[3].

The relationship between architecture and the good society in the context of Utopia/Ideal City can be described on the basis of individual specific ideas, or in general terms, beyond their content. For these are always reflections of specific historical situations. When I speak of Utopia/Ideal City in general, I mean an idea – a project. The point is that the idea (project) is intentional, it has its own inner meaning, it is a construction. In (our own – individual/group) idea we can determine our place, put everything we need into it. The idea is a clearly defined and controllable environment. An idea (project) formulates one particular view of how things work. This should also be the characteristics of an architectural project as such.

Idea_ Content

Collin Rowe calls Utopia (the Ideal City) as we know it from the beginning of the 16th century, until about the French Revolution, the classical one, which did not yet know the messianic image of the architect and the radical transformation of the existing order of things as the modernist one did. The classical utopia, which was more of a mental icon of the good society, had moved into an activist post-Enlightenment phase. The circle of those to whom it was addressed expanded to include the whole of society, and its ambitions shifted from the role of an image to be merely admired to a prescription to be realised.[4] The utopia of the 19th-early 20th century became a direct (political) instrument for the transformation of society. In the post-war period of late modernity, these ideas were displaced from the position of ambitious visions of the future to the autonomy of self-sufficient critiques of society. From the role of a political instrument of power to that of ironic subversive dystopias.

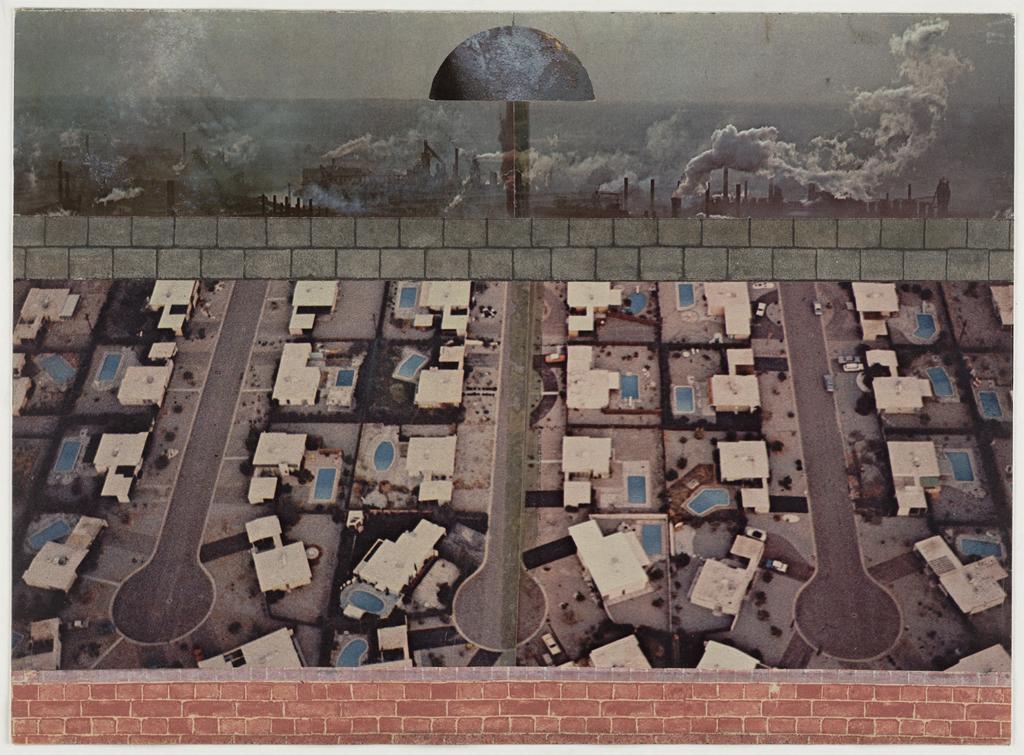

Rem Koolhaas: Exodus, 1972, source: socks-studio.com

Wall_Continuum_Bigamy

“Exodus – or the Voluntary prisoners of architecture” is a project by Rem Koolhaas in collaboration with Elia Zenghelis, Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Viesendorp, for the competition organized by Cassabella magazine in 1972 – “The City as Meaningful Environment”. The project relates to a phenomenon that Koolhaas had already addressed in his thesis at the Architectural Association – “The Berlin wall as Architecture”. The Cold War, an extremely ideologically polarised society, black and white ideas, of which architecture (as a wall) becomes an instrument. In Exodus it is placed in the context of London and separates the Good and Evil half of the city. The Good Half is a walled prison of complacency. Whoever chooses to live in the Good City automatically becomes a (voluntary) prisoner of architecture[5].

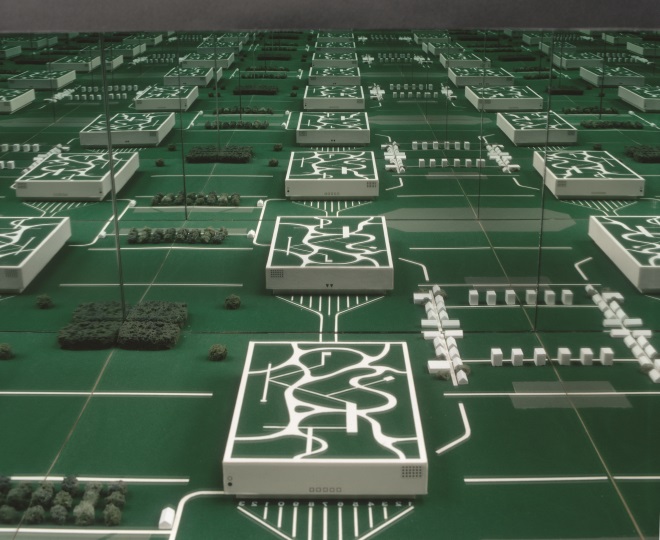

The opposite pole is the “No-stop city” project, by the Italian group Archizoom Associates from 1969. They stripped the city of any articulation, any formal or compositional problems, any quality. A city in which the “aggressive structures of architecture”[6] are absent and, in fact, the city is absent. The multiplicity of individual ideas that the city was has become one large continuous and universal idea of the good society. The city has been replaced by an endless homogeneous structure consisting of residential parking lots, warehouses, sanitation facilities, and bananas.

And then there’s the current idea of a lived-in utopia. 8 House, a mixed-use development on the outskirts of Copenhagen by Danish studio BIG, speaks of infinite happiness. About (almighty) architecture as a direct tool for turning dreams into reality. They question the necessity of a finite choice, because the architect is there to imagine anything, that is, to bring together all that we desire. BIG imagines this phenomenon as bigamy – a multitude of desirable elements that may not fit together, or may even be directly exclusive, but by combining them a new genre is created. “We don’t have to be true to one idea, but combine a multitude of ideas into a promiscuous hybrid.” City block + road structure of a Mediterranean mountain town, that’s 8House.

Andrea Branzi: No-Stop City, 1969, source: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/profiles-and-interviews/interview-with-andrea-branzi

Good_Well

In the first plan, thematically, these Imaginations / Projects / Utopias / Ideal Cities and House illustrate a place where we will all be good together (prescription) or bad together (critique). In the second plan, what matters is how they use architecture (to make us all good together). The good society that utopias talk about does not primarily mean a happy society. The Good Society and the Ideal City are ideas of a structured society through architecture. The formalization of some clearly legible intention. If I go back to the analogous aspects of architecture and the feeling of individual/collective satisfaction, it is the illusion of meaningfulness, (“The City as Meaningful Environment”), the ability to orient oneself in a given environment, the understanding of the projected situation.

Exodus, through black and white optics, speaks of architecture as a border of confrontation of different views. About the tension that has been lost in the No-stop city. Archizoom emancipates society by erasing architecture that is an image of class antagonism. The city has dissolved into one definitive opinion. There has been a permanent hegemony of one idea (in this case, the idea of “grey, atheistic industrialism”[7]). What has disappeared is the city as “the sum of individual figurative episodes”[8], i.e., a diversity of views that have their own formal manifestations.

Utopia in its idealised (pure) form formulates an ideology through architecture. I understand ideology as the relation of society to reality, the way we interpret the world, a set of values,…It illustrates the function of architecture as an articulation of opinion. Therefore, it becomes a political instrument of society. Society is a set of different perspectives, values and visions of reality – ideologies. These can be close or absolutely mutually exclusive; society is pluralistic. According to Chantall Mouffe, (inevitable) political means deciding between conflicting alternatives[9].

Outside

According to BIG, the role of architecture is to combine disparate ideas into a single (all-conforming) whole. It speaks of the good society on the basis of the maximization of content into a treacherous complexity (the fulfillment of all needs and desires). This ideology could be likened to what Mouffe calls a typical liberalist understanding of pluralism. If we bring all (conflicting) values together, they form a harmonious whole. This is based on a belief in a universal rational consensus based on reason, which itself denies the political – the moment of decision.

Against the possibility of complete objectivity and finality of consensus, Mouffe opposes his concept of hegemony. Any actual social order is always hegemonic because it excludes other alternatives. At the same time, it is (supposed to be) temporary, because of the emancipatory aspirations of the suppressed alternatives.[10] This is the idea of a properly functioning dynamic democracy. Architecture materializes, delimits, individual consistent ideational units. But democracy needs (public) space. The (ideal) city should provide heterogeneity and space for confrontation – so that we can all be comfortable together.

Exodus shows architecture as a “condenser of desired possibilities”[11] along with its flip side, when it also becomes an instrument of imprisonment. The image of the metropolis is terrifying in its totality. The benefit of architecture is also its exterior, the possibility to leave it.