Essay / NOWLESSNESS, Lovers

Essay deals with phenomenons of identity, relationships, normalising powers, temporality, queerness, queer art, the Anthropocene, the climate change, the apocalypse etc...The whole essay consists of four chapters which are published separately as a four-part serie.

The emergence of the first ‘queer art’ definitions is dated to 1980s. Despite the fact there had been many representations of homosexuality and lesbianism in the history of art, it was under the influence of feminism (1960s), sexual liberation (1970s) and AIDS crisis (1980s), that the ‘queer aesthetic’ was born. These artworks focused mainly on the social landscape, topics such as life and death, as well as critical exploration of representation and depiction of various subcultures. The most famous artists representing these aesthetics are for example Nan Goldin, Catherine Opie, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Robert Mapplethorpe etc.. The definition of contemporary ‘queer art’ is slightly different. Queer art (and theory) might be defined as a radicalized practice; reexamining how things come to being rather than including broader variety of people into the way things already are. It no longer refers strictly to LGBTQIA-specific issues, it is an embodiment that challenges dominant ways of production, reproduction and representation. It aims to subvert traditional meanings, aesthetics, forms and genres. It is experimental, it is provocative and it is suspicious. It celebrates the failure. It is not an objectifiable identity, domain, or dwelling. It is a strategy challenging the normativity and dominance, always disrupting, refusing and resisting.

Trying to categorically define ‘queer aesthetics’ is a paradoxical attempt, as ‘queer’ by its nature stands in opposition to static meanings and normativity in general.

For centuries we were experiencing general narratives being whitewashed, heteronormatised, censored, misused, adjusted to the current socio-political needs etc.. Great attempts from the side of different minorities was invested into fighting for visibility. This attempt was focused on disruption of the colonial point of view, on the point of view, when ‘we’ are talking about ‘them’ (and vice versa). It is undoubtedly important for subjects belonging to any minority(ies) group(s) within any society(ies) to have their own voice, speaking for themselves. We could see this process on the rise significantly thanks to the evolution of Internet 2.0 and social media, which gave anybody a chance to gain audience for their content, to create new kind(s) of communities, but primarily and most impor- tantly, a chance to share; be it a personal story, an opinion, an artwork, a testimony etc.. With growing inclusivity of the term ‘queer’ – therefore also ‘queer art’ – there are many questions raising that we probably don’t have definitive answers for at the moment. Is inclusivity an open door for normative powers (and its agents) into the ‘queer community’? Can anybody identify as ‘queer’? Do all the artists creating ‘queer art’ identify themselves as ‘queer’? Is it possible for people who do not identify themselves as ‘queer’ to create ‘queer art’? Would we allow them? Would they even want to? What is it precisely that makes ‘queer art’ ‘queer’? The artist behind the artwork? The context of its presentation? The content of the artwork? The audience to which the artwork is designated? Is it up to artists to decide if their artwork is ‘queer’? Can we just label them ‘queer’ despite the fact they don’t identify themselves as such? What would happen to the critical points on normativity? Who has the right to decide what is normative and what is non-normative?

“But now, it is more important than ever to be visible with our otherness. Now is not the time to be conventional or to cut what it is that makes us unique. We must resist those political forces that pressure us to do so, because far more than hair is at risk.”[1]

One of the most well-known ‘queer artists’ is Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957-1996). His work is widely interpreted in context of his life experiences as HIV-positive homosexual Cuban-American man. Many narratives surrounding his work are often limited by its significance solely for the communities to which he belonged. Expanding Gonzalez-Torres’s work beyond his identity and historical contexts surrounding his live, the interpretations we might get are much more universal, while still taking issues of minorities into account. He worked in a field of expanded sculpture, often adopting common objects, such as strings of lightbulbs, clocks, stacks of paper, or packaged hard candies.

“Don’t be afraid of the clocks, they are our time, time has been so generous to us. We imprinted time with the sweet taste of victory. We conquered fate by meeting at a cer- tain TIME in a certain space. We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit [where] it is due: time. We are synchronized, now and forever. I love you.”[2]

Gonzalez-Torres’s piece Untitled (Perfect Lovers) from 1991 consists of two identical, bat- tery powered clocks hung on the wall preferably painted light-blue. The clocks are set to the same time, slowly falling out of synch, until one of them wears down first and initially stops before the other. As it is a well-known fact, that both Gonzalez-Torres and his part- ner Ross Laycock were HIV-positive, this artwork is most often characterised as a metaphorical representation of their unsynchronised deaths. These clocks are so recognizable and commercially available they could pass for the gallery’s own, rather than an actual work of art. It is characteristic for Gonzalez-Torres’s work to take (hetero)normatised ob- ject(s) and then queer it via changes in changed context of its representation. Read as pri- marily useless in their duplication, with initial knowledge of the title of the work, a viewer comprehend the clocks as lovers. It is through their sameness that they initially become same-sex lovers, hung on the wall next to each other, forever touching. If we perceive them as same-sex male lovers, the hands of the clocks might become phallic symbolic evoking anal intercourse at certain moments. It is important to say such interpretations often project excessive sexuality onto the piece. Without much argument connecting these objects to their sexual references, they are reinforcing oversexed gay male stereotypes, fetishizing the artist and his sexual orientation as such.

If we refuse Gonzalez-Torres’s personal identity, he becomes what we might call a non-identity – more of an universal abstract idea, this act is, as well, blurring his relation- ship to Ross Laycock. Generally speaking, any static identity leads to stereotypical depic- tion of various social groups, diminishing variety within any community. Moreover, fixed identities preserve the categories established by normatising social order. We might con- sider a non-identity much more powerful, since it brings instability into the social order, as well as to our understanding of its categorizations. This act encourages the viewers to engage with the work through their own experience without any restrictions and adopted connotations towards any particular identity/community, possibly creating unknown and meaningful connections between different communities. These practices allow subjects from minority(ies) to work inside and outside of the established social orders at the same time. Through strict refusal of a fixed identity we might overcome the identifications as- cribed to minority communities denying their diversity, which fails to recognize that no community is entirely homogeneous. Universal does not contain an ascribed fixed content of its own, it rather addresses the completeness which is absent. Refusing an artist’s, as well as his lovers identity(ies), the audience is able to engage with more inclusive themes of love, loss and longing.

“Change is a powerful thing, people are powerful beings Tryin’ to find the power in me to be faithful Change is a powerful thing, I feel it comin’ in me Maybe by the time Summer’s done I’ll be able to be honest, capable Of holdin’ you in my arms without lettin’ you fall When I don’t feel beautiful or stable Maybe it’s enough to just be where we are because Every time that we run, we don’t know what it’s from Now we finally slow down, we feel close to it There’s a change gonna come, I don’t know where or when But whenever it does, we’ll be here for it”[3]

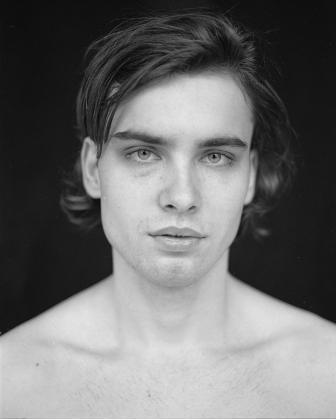

Kotlár, Ľuboš: Untitled (from the series Nowlessness), 2018.