Interview / Lev Rubinstein: RUSSIA IS BOTH HORRIBLE AND BEAUTIFUL, AS ANYTHING CAN HAPPEN

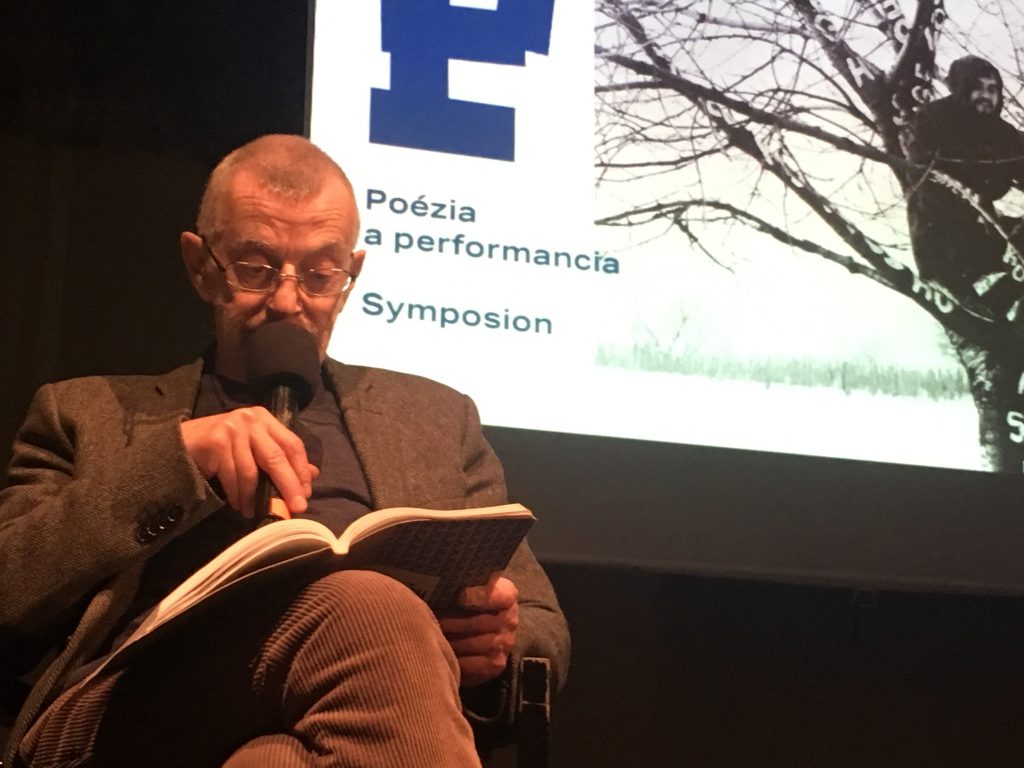

Lev Rubinstein was a guest in Nova synagoga, Zilina, during exhibition Poetry and performance.

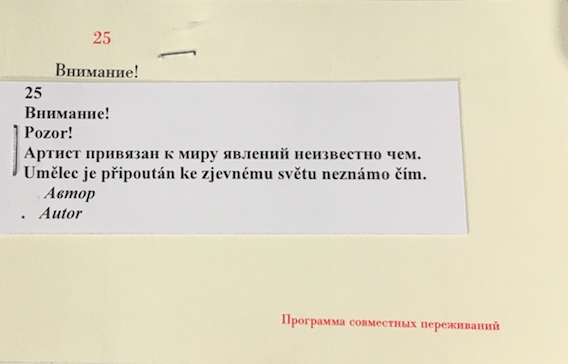

Card from performance.

Lev Rubinstein came to Žilina from Moscow to attend the symposium for the exhibition Poetry and Performance. There he presented his famous 1981 text in the form of sentences on small cards that were passed around the audience.

As he explained, the format of the text came about as a reaction to the then existing possibilities when poetry could be read only at meetings in flats in the circle of close people. The common reading of handful of attendees created a retro illusion of the atmosphere of a 1980s Moscow flat. This interview translated by Tomáš Glanc was made shortly after.

Fedor Blaščák: What was it like in 1980s in Moscow?

Lev Rubinstein: It was a vital test for artists, because art started to become more and more commercial. As soon as perestroika started, western gallery folk and collectors were flocking into Moscow and many artists who had until then worked at home, in cellars, penniless saw great opportunities within what is now called the “Russian boom”. Some of them stood the test very well, some of them failed. The full blossom came with the arrival of Gorbatchev and it reached peak with the Sotheby’s auction.

FB: This was in July 1988. What happened then in Moscow?

LR: I wasn’t there myself, but a lot of my friends took part in it. It was a big thing for our community which confirmed that our art became utterly convertible. For example my friend Grisha Bruskin became “the world champion” in one night (Editor’s note: Brukin’s work Fundamental Lexicon was sold for nearly half a million dollars, being the most expensive sold piece. An exhibition mapping the history of this unique and controversial event is currently held at the Moscow gallery Garage. See the original video recording from the auction here).

FB: Did it also mean the end of one dissident era?

LR: It was a bold episode, but not the end of the era. I don’t think it had any significant influence on the people’s creative work, because who got sold there were mostly artists with a formed clear programme and poetics. There were also those whose destiny was changed by the money. Some of them, let’s say, went crazy, but the majority remained normal.

FB: Was perestroika a renaissance of art in Russia?

LR: It’s hard to tell. I belong to the generation for which 1970s were much more important. It was a decade when important events took place such as the bulldozer exhibition in 1974. Afterwards, many people experienced a certain mental revolution, that’s when the essential opinions were formed. What happened, in my eyes, later during perestroika was that those things and trends that had already been in place got legalised and published.

FB: What were your contacts with the Western world in the 1970s?

LR: Our knowledge of the world and the course of events in the West was very fragmentary. There was some supply of information, there was always somebody who brought something from outside – a magazine or a book, but those were only snippets. We didn’t know anything and we couldn’t copy anything either. That‘s when I found out something interesting: that things can arise concurrently in different places of the world without people knowing each other. All in all, this exhibition in the New Synagogue in Žilina proves it too.

FB: Did you know some people from Czechoslovakia?

LR: No. I knew that art theoretician and critic Jindřich Chalupecký was going to Moscow, but I didn’t get to meet him. I knew the name of Antonín Brousek who was a translator. But for me and my generation, Czechoslovakia was important as a political subject with respect to 1968.

FB: The opinions were defined in the 1970s, they were legalised exported to the world in the 1980s – what did the 1990s then brought new?

LR: The problems of my own country never worried me so much like then. It was something truly exceptional even for me. The 1990s were the freest period of the whole history of Russia. We even thought that Russia could become a European society. Of course, later this turned out to be a mistake. But it was a sort of freedom precedence that gives me hope even today. At the same time, our community of artists began to fall apart by then, loads of people left.

FB: Do you agree with the opinion that political oppression makes a greater need of artists to create?

LR: I know it. I, too, was growing up in a totalitarian regime and it’s true in a way, because when the pressure comes from different sides, one needs to build some inner freedom in oneself. But if I don’t want to be just egocentric, I have to sacrifice my advantages in favour of the fight for more freedom in the country. Every artist somehow feels this pressure from his/her surroundings and everyone seeks to oppose it one way or another. Lack of freedom is always a great challenge, but it’s the type of a test we are already familiar with. Freedom is also a sort of challenge, but we don’t know it too much in Russia and that’s why it would be better to try this version, for a change.

FB: When will it happen?

LR: (laughing) Interesting question. If I only know it… but I won’t make any prognoses here, especially they relate to Russia, because Russia is both horrible and beautiful, as anything can happen. The situation there is therefore always unpredictable.

FB: We are going to hope.

LR: Exactly.

Lev Rubinstejn in Nova Synagoga ZIlina.