Essay / PALLADIO OF THE SUBURBS

About a year ago, we have asked the architect and curator Daniel Tudor Munteanu, to review two houses, that are conceptually and contextually similar – LJM by N/A architects and House in a House by PLURAL. We have received the review in a form of a dialogue – about the houses themselves, but also about reviewing architecture and its perception via representation in our age.

LJM by N/A

House in a House by Plural

Daniel Tudor Munteanu: Davide, this invitation to write a review about these houses came from some very good friends – Michal Janák and Martin Jančok, from the Slovak architecture office Plural. I had visited their House in a House in Bernolákovo twice. Two years ago, I was in Bratislava for a lecture and Martin took me to see this project, which was still in construction. Last year, they asked if I would be interested in writing about it; I was in Brno at the time, and we quickly drove to Bratislava to check the finished house, before heading to the Vienna airport. The project received its fair share of attention from the media. It was published by Dezeen¹, for example, but without any added critique – just a bunch of photographs and the PR text self-written by the architects, which is quite a common thing today for these big architectural websites. Plural, however, wanted an unbiased opinion-piece from a critic (which I’m not!), so they commissioned me to write a review for MAG D A magazine, in which to relate their house to another project – the LJM House by N/A (Benjamín Bradňanský and Vito Halada).

Davide Tommaso Ferrando: So you’ve visited both houses?

DTM: Yes, I visited both in the same day, one after the other. They are located in the rural suburbs of Bratislava, quite close to one another. However, I find myself in an awkward situation – as I said, I don’t consider myself a critic. All my writings have been so far related to personal interest; I choose my own subjects and I’m not accustomed to write commissioned reviews. That’s why I’m proposing to instead have this conversation: you are a professional critic, but you’ve never seen these projects in real life, while I’m a dilettante but, let’s say, with more insider info.

DTF: This might get interesting. Few publications still value real architectural criticism. The Architectural Review commissioned me a paid text² about Gloria Cabral, the partner of Solano Benítez. I was probably someone eligible for doing that because I know these architects personally, I had long conversations with them, but I had never been to Paraguay! So I was supposed to write about things I’ve never seen, solely based on their descriptions – the pictures and drawings they’ve sent me. So, on one side, yes, they just needed someone to do the job, and my review was judged probably only in stylistic terms. On the other hand, at quite the same time I wrote another text for Casabella, about Valle Architetti’s Fantoni Factory in Udine. I went to the place, I saw it, I spoke to the architect and the owner, I went to the archives, I got all the materials with all the drawings and all the details, I had a lot of time to write, but then…

DTM: You were not paid!

DTF: Zero! Nothing, not even a free copy of the magazine. I had to buy it myself. And, at the very same time, I don’t know if you’ve read that issue, but the other articles are really badly written. So, this is one of the big issues. It doesn’t feel strange to me that Plural didn’t got any critical texts written on their project, because many magazines seems to have stopped caring about criticism anymore. You know that I’m now involved in the Little Italy project – a survey of the new generation of Italian architects. And, among others, I’ve asked two specific questions. The first was how many times have your projects been published, in print or online? All of the 140 architects who took part in this survey answered that their projects have been published somewhere, sometimes to the point that they can’t keep track of all the links… The second question was: has someone written an original text about your work? Basically, with very few exceptions, their answers were all negative. This is an issue I’m very much interested in: on one side, everything that is produced is published nowadays; at the same time, the use of these documents has become exclusively considered as advertising, for both the architects and the magazines… Criticism used to be very useful; when someone starts to think about what you’ve done, analyzes it, finds references, puts it in relation with the rest of the discipline and of the contemporary production… it allows the authors to better understand what they have done. Because, often, architects gain through criticism a better understanding of their own work. But few criticize the current production so, basically, it seems that everything is good! No architect and no photographer will ever show those parts of the buildings which are not well resolved, those details which don’t work, so you get a very biased version of your project, because everything that’s written about it is just positive, and everything that’s shown about the projects is just beautiful!

DTM: There’s now this distinction about users and readers. The magazines used to have readers and, possibly, few of them still do, while the websites have simply users. Everything that counts is their number of clicks, that’s it. Is there anyone who still reads Archdaily’s texts? I guess not. It’s just a fast consumption of pictures… I believe that nowadays the best (and only?) critic that ‘reviews’ the buildings is the photographer commissioned to shoot those projects; if he’s a good photographer, he’ll also assume the role of the critic. Look what’s happening now with the intimate collaboration between Bas Princen and Office KGDVS, or between Filip Dujardin and Jan de Vylder’s atelier. I don’t remember very good texts about Office KGDVS’s production, but Bas Princen’s photographs offer a very rich critical perspective on it. The photographer is perhaps the only guy who still has the chance to experience those projects in real life, because no magazine budget allows anymore for the critic to travel…

DTF: These topics are very interesting. Of the photographer as the last surviving critic and of the critics who write based solely on photographs and drawings… which, very often, are manipulated. If you look carefully, sometimes they don’t exactly correlate with one another. These baudrillardian simulacra have sometime no correspondence in reality, but we convince ourselves they are the reality. As Beatriz Colomina says, “from the moment into which architecture enters into the realm of mass-media, it becomes a media itself”. Basically I’m forced to evaluate buildings I’ve never seen, through the biased pictures of someone who’s not neutral; and we daily see so many buildings on the internet, knowing at the same time that we’ll never see 99% in real life. And I’m talking here even about super-famous buildings, like Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, that we might never get the chance to see, because it’s so far away. We consume architecture through images and I still believe critical writing has a very important role, because words can still break this kind of enchantment that the images are producing. Through words we can explain things that are not visible in the images. Remember Loos, who said that ideally, architects should not use drawings, but only words. Still, we stopped reading the texts on, for example, Archdaily. The way in which we consume content on the web is distracted, fast, fragmented. To read something on the web is difficult, it’s true, you really need to concentrate to get to the end of an article; but the main reason we don’t read such texts is because we know beforehand, consciously or unconsciously, that these texts are worthless… The expectation is already very low: why should I read it when I already know that this is probably marketing blah-blah produced by the same studios that designed the buildings? Yet, I’m kind of sure that, if you produce the expectations for good reviews, a certain amount of people would still read those texts.

DTM: I want to tackle some more subjects in this conversation and this broad topic of the review, of the critical evaluation of a private project, is really intriguing for me, because the reviews are meant for some others to get an expert opinion, like a post-scriptum, after you’ve already experienced the thing (being it a movie, book, exhibition, whatever). But, for this kind of private programs, the review and the adjoining photo sets are all that remains in the public domain, because one can never go to actually see and experience the real thing.

DTF: But this goes not only for the private projects, but basically 99% of the architecture that we know.

DTM: Indeed. However, one might still get a chance to encounter the architectures that you refer to, as a casual passer-by, or at least to get a taste of their publicly accessible parts. But, in our case, both houses are in the middle of nowhere, in that even covered field that is neither rural or urban, but just an endless landscape of private houses, infrastructure and agricultural fields.

Another funny thing: both projects were covered in Mark magazine by a very dear friend of mine, a really good architecture critic from Prague, who (of course!) hasn’t had the chance to experience them in real life but, still, he had to produce some very fast texts and catchy titles to adjoin the images. And, here we are, a Romanian architect and an Italian critic, trying to write about these two projects in Slovakia… How do you explain this proposition of the authors for us to make a mirror-review of the two projects? It seems that, for the authors at least, they seem to share quite a lot of similarities

DTF: One thing that is very easy to see (perhaps because of the way they chose to communicate their concepts, so I see this because they wanted me to see it) is the clear structure of the floorplans which, somehow, have a sort of a classic reference. Both villas start from a regular floorplan, but they add some geometry around it (in both plan and section) to enrich the scheme, to add more spatial complexity and variation to the box. If I really have to find some similarities then, of course, they both share similar aesthetics of rough concrete and warm wood, they both have a similar mediated relationship with the surroundings but, to be honest, what I’m more interested in is that both projects belong to this category of projects that I document on realismoutopico. These are projects that have one or two ‘good moves’, either in terms of materials, space, functional distribution, etc.; the projects work in an interesting way around a couple of main topics, and the rest just works nicely around these one-two good ideas. What happens is that you have projects which are easy to understand, which is good in a mediatic environment with fast and superficial access to information. At the same time, these projects will not enter the history of architecture, precisely because these kind of projects work in just a couple of things, and not on everything that they have at their disposal. Today, most of the architectures I’m interested in have this sort of balance between really clever moves and then the rest of the project, probably because you don’t have the possibility to work on every single detail and every single topic to bring more and more complexity. On the other hand, many architectures that are published in big and mainstream magazines, like those huge urban projects by the big offices and so on, apparently they are working on a lot of topics at the same time but in reality they don’t in fact work on anything other then the final image of the project in itself. That’s why I’m interested in these small projects where you see that there is the possibility to make some specific research about design, and to bring this research forward and to make it real. If the project itself is not going to be a masterpiece, it doesn’t matter, because it’s still good architecture that you learn something from. It’s architecture that produces architecture, because it becomes part of the filter through which I look at the rest of architecture, through which I design or through which I write. In this sense, I feel that these two projects give some clever hints about some clever moves that can be done about architecture. These are good projects and I’m happy that you showed them to me. Still, I base my opinion only on the documents that you’ve shown. You’ve visited both, so what’s your opinion about them?

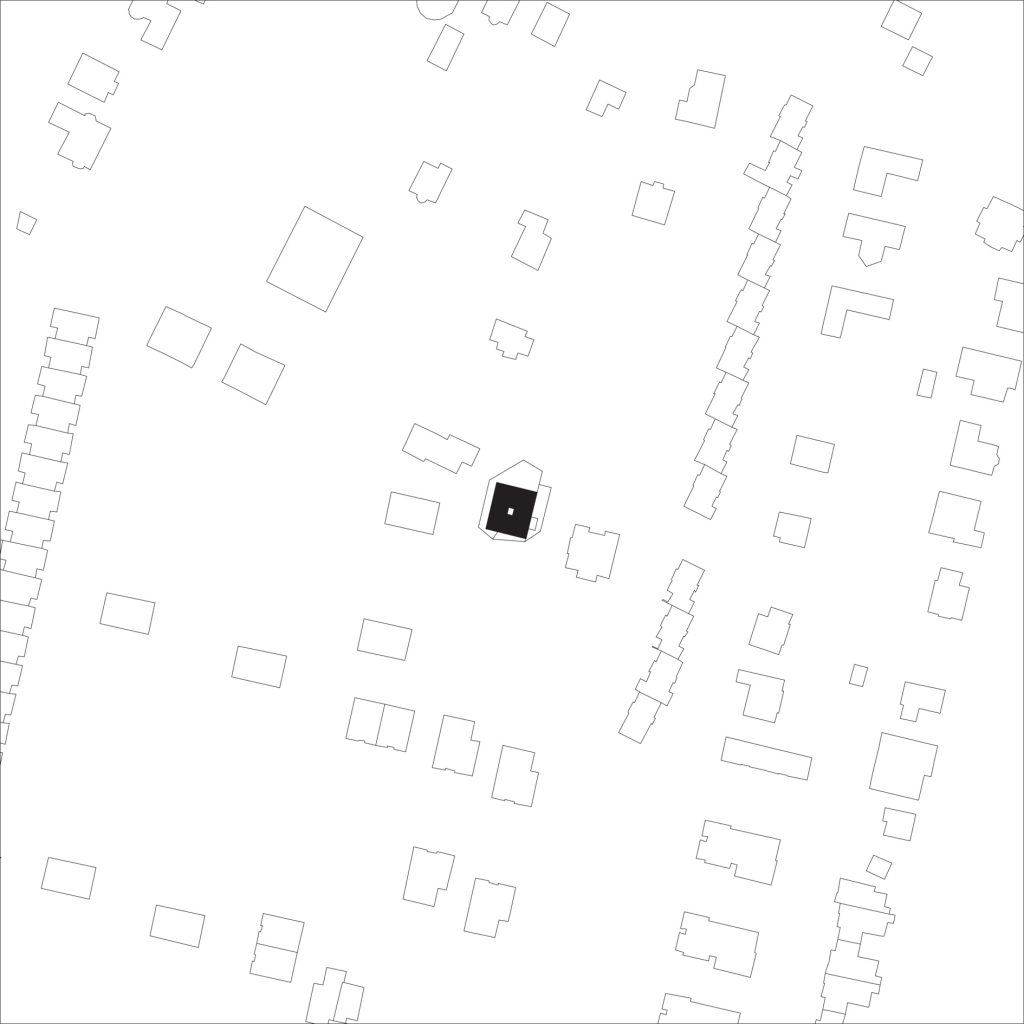

DTM: Well, you mentioned the term villa, but these are in fact small unluxurious bungalows on very small suburban plots. Both teams speak literally about references of the Palladian villa, but isn’t it strange to talk about a villa when dealing with such context? I feel that in a villa, the endless landscape around it is more important than the building itself. But here there’s no pastoral landscape, but an uncertain melting pot of developer row housing schemes, old rural houses and new middle class individual houses, many still in construction. The context is in the making, so to speak.

Still, Palladio’s influence is I think legible in both projects, in terms of composition or, in fact, of non-composition! The little houses are both based on the 9-square-grid, which is the non-compositional device per se. What Loos said about using words instead of drawings perfectly applies in these cases: you can communicate their organization in words or, even better, as instructions. I was very happy with the way both teams tried to mediate the relation between these little houses and their dull surroundings. The clever moves that you mentioned are here the addition of a second layer, a sort of a second facade, a permeable unnecessary wall around the houses, that adds necessary complexity to otherwise modest commissions. And these walls coincide somehow with the limits of the plots. The LJM House is located on a non-rectangular plot, and these given boundary lines dictate the slightly distorted geometry of its second facade.

The lateral facades of the House in a House again coincide with the plot boundary, more orthogonal in this case. All the attention of the architects is focused on these second facades and on what’s happening in the no-man’s land between the houses themselves and the second layer of perimeter walls.

I’m not interested here in discussing their stylistic choices. It’s so easy to see that N/A went towards the style of, say, early SANAA or Sou Fujimoto, with exposed concrete walls punctured by square holes in an arbitrary fashion, while Plural felt more at ease with the industrial aesthetic of translucent polycarbonate coined 20 years ago by Lacaton Vassal or Abalos & Herreros.

DTF: I completely agree with you when you say that you are not interested in the language, or choice of linguistic references that these two architectures show. One of the main risks of this communication of architecture that is exclusively based on images is that, more and more, everything is reduced to language, to style. Especially today, when the easiest thing to do is to make references from one project to the other solely based on images that look more or less the same. That’s really the poorest and most superficial way you can speak about architecture, to reduce everything to the level of outside appearance.

DTM: Indeed. Forgetting everything that has to do with style, what really interests me is the cleverness of the architects, who used these second facades as a way to enhance the context as seen from the inside of the house – either by blurring it, or by pixelating it. Just like applying a Photoshop or Instagram filter on an otherwise dull image.

DTF: And at the same time it also creates a background on which to project the life in the house.

DTM: Yes. It’s an inside-outside direction.

The other way around, and I’m speaking here of the way these buildings deal with their neighborhoods, there are also some clever moves.

Both houses mess with the mandatory street alignment. As such, they affirm themselves as objects, as exceptions in the urban fabric, as ways to counteract the monotony of the streetscape.The House in a House is set back, allowing a very generous front garden as a sort of gift to the street. There was an old building on that plot and the new project stands exactly in its former place, not aligned with the neighboring facades. The topography is also interesting, because the ground level is slightly raised from the street, and the crossing of this front garden is ascensional, like in the Palladian villas.

In the case of the LJM House, the situation is reversed – the front garden is contained in the volume of the house, because the facade grows straight from the sidewalk. In fact, the architects convinced the planning authorities that this is not the elevation of the house, but just an oversized concrete fence. Topographic accidents are also happening here, but this time they are man-made: the level of the front inner garden is raised by 1 meter, to the level of the windowsills. You don’t necessarily notice this from the street, except if someone is using the garden behind the fence – through the square openings some unusually tall neighbors might as such greet the passer-by. And, also, there’s some generosity in the relation to the street as well: a corner of the parcel is simply cut-off from the house and offered as an improbable gift to the neighborhood. Sooner or later a bench or a drinking fountain will for sure appear in this unexpected sidewalk pocket.

DTF: The tweakening of the norms is one of the most interesting parts of design. Even though it’s not much narrated, you see so many incredible projects coming out of a creative interpretation of the norm. MVRDV theoreticized it many years ago, but also Arno Brandlhuber is working on this in super interesting ways, or Stefano Pujatti of ElasticoSpa. If such projects are built, they might trigger a change of the normative, because the reality is much stronger than the norm itself, which is only made of words. If you manage to jump the fence of the law, then at the very same time you begin questioning the law itself. Again, we’re talking about images and words – words are always interpretable.

DTM: Not only the law is interpretable, but also the client brief. I feel that the place where the architects were truly allowed to pursue their own agenda is exactly in the no man’s land between the house and the street, between the client brief and the planning regulations. This grey zone is, in the case of the LJM House, the surreal collage of landscapes that surrounds the house, from the sort of Japanese rock garden that adjoins the living room to the little artificial hill into which the bedrooms are sunk. In the case of the House in a House, the no man’s land around the main body of the house is less spiritual, but functional; everything that didn’t fit inside the house unfolds in there: a carport, a tool shed, a small swimming pool, a terrace with basement access, etc., like objects casually scattered on a table. Thank you Davide for this conversation and your insightful comments and let’s just hope it will make sense for anyone who’ll stumble upon it online. In the age of the likes, it sounds slightly anachronistic.

¹

Amy Frearson. “Plural completes plastic-clad house in Slovakia with inner and outer layers.” Dezeen.com. https://www.dezeen.com/2016/08/12/plural-plastic-polycarbonate-clad-house-swimming-pool-bernolakovo-slovakia/

²

Davide Tommaso Ferrando. “Breaking the mould: Gloria Cabral, Gabinete de Arquitectura, Paraguay.” The Architectural Review, March 2018. online: https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/breaking-the-mould-gloria-cabral-gabinete-de-arquitectura-paraguay/10028553.article

Daniel Tudor Munteanu is a practicing architect and urban planner based in Suceava, Romania. He was educated in Romania and The Netherlands, has exhibited at the 5th Urbanism\Architecture Bi-city Biennale in Shenzhen and has contributed to OfficeUS, the U.S. Pavilion for the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale. His texts and graphic essays were published in San Rocco, Volume, Log and Oase. In 2015 he curated the ‘Aformal Academy/Pedagogical Infrastructure’ chapter for the 6th Shenzhen Urbanism\Architecture Bi-city Biennale and contributed to the State of the Art of Architecture project for the Chicago Architecture Biennale. In 2016 and 2018 he was the co-curator of the Unfolding Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Daniel is the founder and editor of the research project OfHouses – a collection of old forgotten houses.

Davide Tommaso Ferrando is an architecture researcher and critic, particularly interested in the intersections between architecture, city and media. M.Arch in Advanced Architectural Design at ETSA Madrid and PhD in Architecture and Building Design at Politecnico di Torino, he is Post-Doc University Assistant in the Department of Architectural Theory and History at the University of Innsbruck. Director of 011+ and vice-director of Viceversa, his writings are published in collective books and international magazines such as The Architectural Review, Casabella and Project. In 2016, he was co-curator of the Unfolding Pavilion, and scientific consultant for the Meeting the Commons section of the Italian Pavilion at the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale. In 2017, he is curator with Nina Bassoli of the Festival Architettura in Città of Torino. In 2018 he was, together with Daniel Tudor Munteanu and Sara Favargiotii, curator of the Unfolding Pavilion at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale.