Interview / DANIELA AND LINDA DOSTÁLKOVÁ

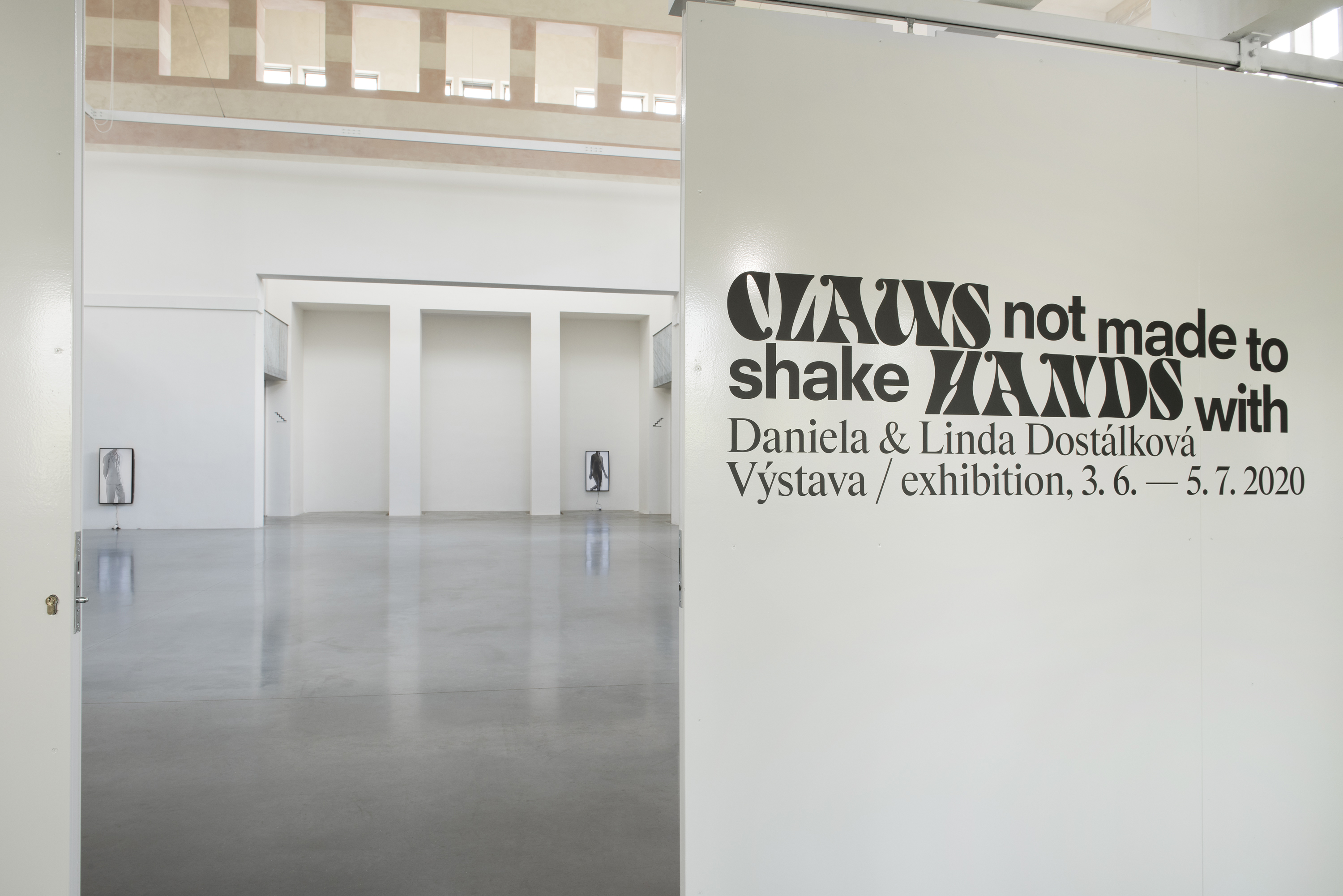

(Slovenčina) Rozhovor s Danielou a Lindou Dostálkovou nielen o výstave CLAWS NOT MADE TO SHAKE HANDS WITH, ktorá sa nedávno uskutočnila v Novej synagóge v Žiline.

Photo: archive of Daniela and Linda.

LH: You opened the exhibition in the New Synagogue in Žilina just after the strict quarantine was loosened, you were only allowed to come to Slovakia for 48 hours. Someone said during that period that we were living history again. How did you experience this period, did it reflect in any way in the exhibition or its production?

DLD: The announcement of the quarantine came just a day before the planned filming of the videos for our exhibition called Claws Not Made to Shake Hands With, which was preceded by quite demanding production preparations. We finally decided to cancel the filming. But in a way it was liberating. After about a week off, we started to think of an alternative plan to do without the agreed actors and a professional studio.

So we set up a provisional space in our apartment – it was quite a different way of working, especially since we don’t usually photograph ourselves – we had been working with carefully chosen protagonists until then.

We then returned to studio work again when we shot the videos, but it was the experience of the provisional studio that preceded it. For a long time it looked like we wouldn’t be able to install the exhibition in person, and we finally did, thanks to the opening of the borders just before the exhibition for 48 hours and then, paradoxically, on the opening day.

Photo: archive of Daniela and Linda.

You’ve been described as ecofeminists, and overall you’re close to activism in the arts. The works that were created for the exhibition in Žilina have similar starting points. To some extent they are also a continuation of your last year’s theme from the exhibition Campaign (Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague). You mentioned at the opening that you are not opposed to your works being used, for example, by animal rights activists for a mobilisation campaign. When did you become more pronounced in this direction? What was formative for you in this direction? Have you been actively collaborating with any eco-activist groups?

Our long-standing plan, which we always keep in mind when researching and preparing new works, is the idea that they can also function as an activist campaign in themselves. It took some time to see if this was even realistic. We are currently discussing such a use.

We’ve been dealing with the position of women and animals since forever, it’s just been a long time coming, and we’re still evaluating how to communicate it. The discourse in contemporary art has changed several times in the meantime, and we observe a number of arbiters who proclaim what forms of activism have relevance and what forms don’t. So, going back to how we work: we want to be radical, but we also want to give space for the viewer to find that radicality in our work. How do you react when a video of a massacre starts playing in front of you on social media? We dare to say that not many people have the courage to watch the whole thing; instead, they prefer, for example, the story of the pelican whose beak is untangled by fishermen trapped in plastic waste, because there is a happy ending. And that’s the scale we’re on.

We came to this topic primarily thanks to the campaigns of the anarchist group Bite Back, which are entirely documentary in nature and direct action. The group’s members often break the law – on the cover of the magazine of the same name, they are pictured wearing black balaclavas, holding animals rescued from laboratories, or documenting entire landscapes, from trashed feedlots in the woods to the torsos of charred vans parked outside meatpacking plants. We were very struck by their form of communication, and found it all the more shocking when we first publicly shared the research materials of this and related activist groups at a foreign institution about five years ago – most of our colleagues found our presentation highly entertaining. It was the same feeling that you might get when you watch a mother at the cradle with a sleeping child and a lit cigarette in a 1950s movie, and many other situations that are unacceptable from today’s perspective and are separated by a really thin line. It is precisely this form of lack of understanding and empathy that makes us systematically address animal protection.

In the exhibition you also deal with gender themes, from your point of view men have a more isolated and heroic approach, which is problematic in improving human-animal relations, while women, in your opinion, can relate better to animals, they are more open and caring. Is your goal to emancipate women more in activist movements?

The dichotomies between mind and body, animal and human, organism and machine, public and private, nature and culture, male and female, primitive and civilised are constantly being ideologically challenged. Above all, our aim is to convey to all who are willing to listen that care and concern can take different forms. And that it is perfectly legitimate to find one’s own way to realize it.

In the texts of the catalogue for the exhibition in Žilina, you blur genders and species – you want it to be unclear whether it says woman, man, animal….You write there about a new mutual “domestication” between man and animal. Are you also new “domesticators”?

For us, a certain key to grasping the exhibition is the author’s text, which we have tried to freely compose so that it is not entirely clear from which position the described situations are addressed. We decided to do so, especially in the pictorial representation, in an attempt to exorcise the entrenched human/animal hierarchy, because it is the human who is convinced that he defines this hierarchy. We believe that the history of domestication can no longer be seen as a unidirectional development, but that there is a mutual domestication in interaction with the animal.

Photo: archive of Daniela and Linda.

You’re sisters and you’ve been working as a couple for a long time – you don’t label the work, when did you realise that it was important to you and that you wanted to do it that way?

Our lives, as well as our practices, have always been very intertwined, but we realized that we complemented each other in a fundamental way through our collaboration on the book I Was Not Able to Visit the Entire Show in 2015, which was a play for two actors and a chorus with the premise of a staged performance in gallery institutions. Also important for us was the Exhibition, to which we were approached by Marek Pokorný, after which he subsequently invited us to participate in the conceptual design of PLATO Ostrava in the space of the former Bauhaus hobby-market.

You live in Prague, you have a strong background in Poland, you have done various international residencies, teaching, you are curators at the PLATO gallery in Ostrava. Where do you feel the best at the moment and what keeps you most busy?

In the last few years, our art practice has kept us most busy, but it certainly makes sense for us to have a broader connection of all the activities you mention.

Is there anything that really irritates you in the current operating of the art institutions? You said, for example, that you don’t like it when too much is said at an opening and the viewer can become lazier as a result. So how do you feel about the trend of mediators in contemporary gallery operations?

We often perceive many gallery institutions and their methodology as ideal adepts of the competition for the best newsletter. All the energy and expectations of the team towards the viewer are accumulated around the imaginary newsletter (you can replace it with any communication tool of gallery vs. viewer). And yet, perhaps a more proactive turn would have been enough, which not only the visitor to the institution itself, but also its team will only realise later, giving both parties a chance to show their openness and thus break the established order. For us personally, this is a fertile ground and a reason to visit galleries and to cooperate with them.

It’s as if the exhibition is a danger zone that we have to guide the viewer through in order to give them a chance to understand something. The whole range of fears of the operators leads to the viewer throwing away their judgement, completely convinced that they will be given a set of pre-announced clues that they will either accept or not. Thus the whole range of possible interaction disappears and the whole situation suddenly becomes flat and predictable, and for some artists can be binding.

In addition to your freelance work, you also do advertising campaigns, mainly for cultural institutions, but also for Vogue, for example. Which of the collaborations was important or different for you in this respect and why? And why not have this extensive layer of your work on your website?

Perhaps we would rather replace the term you mention with the term visual identity in our context of the various forms of cooperation and especially the clients we have worked with so far. We are therefore the authors of a number of hybrid defined identities, including the exhibition of ING Bank’s collection The Spirit of Nature and other commissions at the Silesian Museum in Katowice, where our work was also created as a visual representation of the exhibition, the Institute of Anxiety, and the campaign for the drama ensemble of the National Theatre in Prague 2019/20. We are working on the identity for the catalogue of the Neumarkt Theatre in Zurich, the POP Filozofie publishing house, and many others.

In collaboration with VOGUE CS, we have produced several photo editorials, including Cute vs. Wild Paradox in which we address the problem of animal ethics, so-called speciesism (discrimination against certain animal species). We have also published a series of fashion photographs called Circulation, inspired by a text by the artist Hito Steyerl, in which we explore the speculative panorama of image post-production. Then, on the cover of the previous, pandemic issue, you can see our photograph from the series Quality: Flexibility, which critically relates to the limited possibility of movement of the artist in the contemporary scene.

As you say, we take a deliberately intuitive approach to the content of our site. We are going to add a number of implementations there. However, we believe our work shows that we have the ability to operate in a broader context. We often find ourselves in situations outside of normal institutional mechanisms, and these require a great deal of attention and empathy in the variations of the possible exercise of our own autonomy. We have to say that these situations certainly keep us going.

How did you find working with the New Synagogue?

Marek Adamov and the whole New Synagogue team are working with great dedication and it’s great to be there and watch it. Thank you so much for that!

I thank you for the interview.